In a documentary about this Turner’s painting of Venice, Bacarolla is the background music, it really enhances the appreciation of the painting, explains from the perspective of neuroscience.

ChatGPT: The pairing of Offenbach’s Barcarolle with Turner’s painting “Venice Quay, the Riva degli Schiavoni” (1844) creates a multisensory experience that significantly enhances emotional and aesthetic appreciation—and neuroscience can explain why.

🧠 How the Brain Reacts to Art and Music Together

1.

Multisensory Integration – The Brain as a Synthesizer

- The superior temporal sulcus and posterior parietal cortex are responsible for combining different sensory modalities (vision + sound).

- When you look at Turner’s hazy, light-filled Venice while listening to the swaying rhythm of Barcarolle, your brain fuses the two into a single, enhanced emotional impression.

- This binding process deepens memory, mood, and meaning.

Result: You don’t just see the painting—you feel it move and breathe.

2.

Mirror Neurons and Emotional Resonance

- Music like Barcarolle activates mirror neuron systems, allowing the listener to empathize with the emotional tone of the song.

- The gentle duet creates a sense of intimacy and stillness, matching the soft dissolving forms in Turner’s painting.

- This alignment evokes a feeling of romantic reverie—as if one is drifting, both literally (on a gondola) and metaphorically (through time and memory).

The viewer’s brain mirrors the serenity and longing both in sound and image.

3.

Dopaminergic Reward Pathways – Pleasure in Harmony

- The mesolimbic system, especially the nucleus accumbens, releases dopamine in response to musical and visual beauty—especially when the two align in tone.

- Turner’s golden light, soft focus, and dreamy water reflections act like visual harmony.

- Barcarolle’s swaying rhythm and melodic consonance create auditory harmony.

When these harmonies match emotionally, your brain’s reward system lights up more intensely than for either one alone.

4.

The Default Mode Network (DMN) – Imagination and Memory

- Both Turner’s painting and Offenbach’s music invite internal wandering: romantic memory, daydreaming, fantasy.

- The DMN becomes active, linking the viewer’s personal memories of water, light, love—or imagined ones.

This mental drift amplifies the painting’s emotional pull beyond the visual.

5.

Temporal Entrainment – Barcarolle and the Gaze

- The 6/8 rhythm of the music subtly entrains the viewer’s attention: the eyes move more slowly, gently, in sync with the sway of the music.

- This slows perception, allowing the viewer to absorb Turner’s soft transitions and atmospheric dissolves more deeply.

The music paces the gaze, making the painting feel alive and cinematic.

🎨🎶 Conclusion:

Pairing Barcarolle with Turner’s Venetian mist and glimmer isn’t just poetic—it’s neuroaesthetic.

It works because:

- Both trigger parallel emotional circuits

- They entrain attention in a fluid, dreamlike rhythm

- The brain binds them into a single, emotionally heightened memory

You don’t just see Turner’s Venice—you float through it.

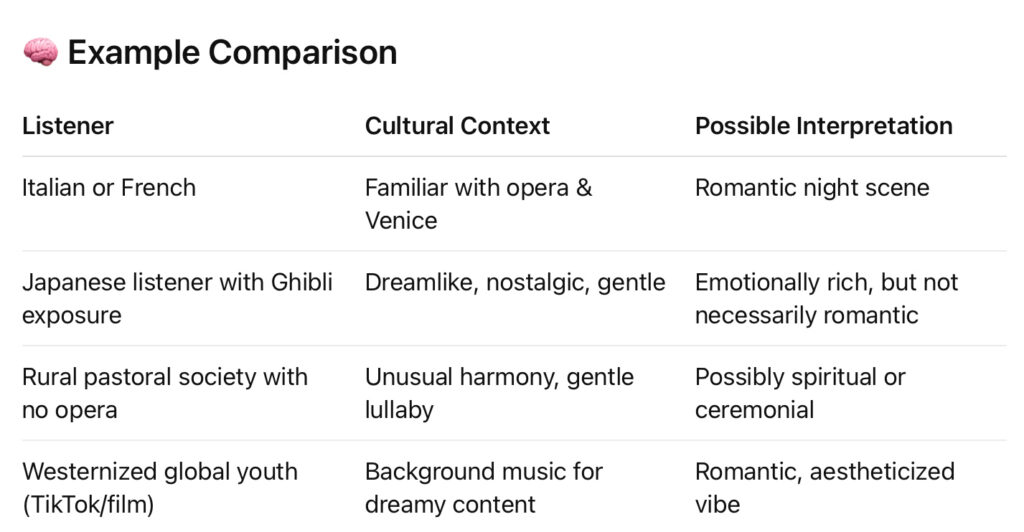

From the perspective of anthropology, how do people react without the pre-knowledge of Venice or the interpretation of song? Could they still feel the romantic connection? Or the reaction is pre determined by culture?

ChatGPT :

This is a profound and nuanced question. From the anthropological perspective, the answer lies at the intersection of universal human capacities and cultural conditioning.

🌍 Can people without pre-knowledge of Venice or the song still feel the romance?

Yes — to a degree.

But how they feel, interpret, or assign meaning to the feeling often depends on their cultural framework.

🧬 1.

Universals in Human Perception (Cross-Cultural Tendencies)

Anthropologists like Alan Lomax and ethnomusicologists like John Blacking showed that:

- Certain musical features (slow tempo, soft dynamics, harmonious intervals) are universally associated with calm, intimacy, and emotional depth.

- The lilting 6/8 rhythm of the Barcarolle mimics human movement—rocking a baby, swaying during courtship—which creates a somatic (bodily) sense of safety or tenderness.

- Vocal harmonization, especially female duets in thirds and sixths, can sound soothing or intimate across cultures—even when the language is unknown.

So yes, even without Venice or a translation, many listeners could feel that the song is “about love” or “about something beautiful and intimate.”

🌐 2.

But Meaning Is Filtered Through Culture

- In cultures that do not use Western tonality, the harmonic and melodic structure may not immediately signal “romance”—it might sound “foreign,” ceremonial, or neutral.

- Venetian gondolas, moonlit canals, European femininity are all Western cultural icons. Without those associations, the listener doesn’t imagine Venice—they imagine something else, or nothing at all.

- In some societies, romance is not publicly sung about; emotional restraint is more valued than expression. So the reaction may be aesthetic, but not personally romantic.

The emotion might be felt—but its interpretation depends on the cultural “lens.”

📖 3.

Cultural Scripts and Musical Semiotics

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote about how culture is a “web of meaning”. In music:

- We “read” songs through semiotic scripts (signs and meanings we’ve learned).

- The Barcarolle’s meaning in the West = “Venice + Night + Love”

But in another culture, the same sonority might signify ritual purity, mourning, or pastoral nostalgia.

🎵 Conclusion:

- Romantic response to the Barcarolle is partly universal (sound as feeling)

- But its meaning—Venice, love, night—is culturally coded

So people without pre-knowledge can feel, but what they think they’re feeling (and why) is largely a cultural construct.

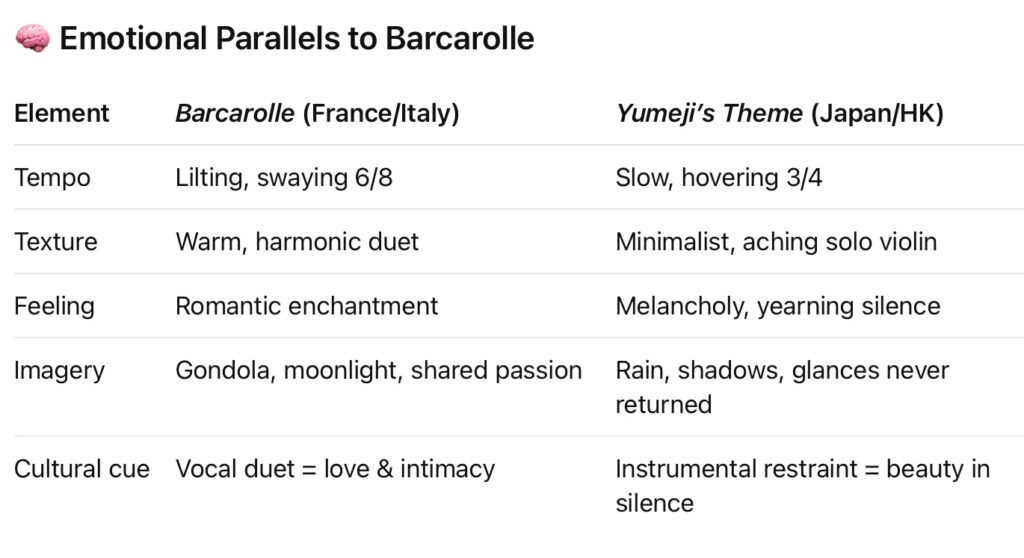

Let’s explore a non-Western musical piece that evokes similar dreamy or romantic emotions to Offenbach’s Barcarolle—but through entirely different musical structures and cultural meanings.

🎵 Example:

“Yumeji’s Theme”

from

In the Mood for Love

(2000)

Context: Accompanies scenes of unspoken love and emotional tension in Wong Kar-wai’s film

Composer: Shigeru Umebayashi

Origin: Japan/Hong Kong

Style: Slow, minor-key waltz with bowed strings and restrained phrasing

🔍 Anthropological Insight:

- In Barcarolle, love is sung, externalized, and illuminated by moonlight.

- In Yumeji’s Theme, love is withheld, internalized, and shaped by social norms of restraint—especially in traditional East Asian cultures where emotion is often expressed through subtle gestures rather than overt confession.

Yet both pieces stir the limbic system, and both evoke longing—but one expresses it as shared rapture, the other as quiet ache.

🎼 Other Non-Western Parallels

1.

North Indian Raga – Raga Yaman

- Played at twilight, often associated with love and yearning.

- Uses microtonal bends, drone accompaniment, and melodic improvisation to create a meditative emotional state.

- No harmony or fixed rhythm like Barcarolle, yet listeners often report feeling a sense of floating tenderness.

2.

Persian Classical Music – Dastgah Mahur

- Considered bright and lyrical—often performed on instruments like kamancheh or setar.

- The melodic lines unfold slowly, evoking subtle emotional colors without overt “romantic” cues.

- A poetic listener might still associate it with love or beauty, even if those aren’t culturally explicit.

🪞 Final Thought:

Across cultures, music can access shared human emotions, but each culture builds its own emotional language from those feelings.

- Barcarolle speaks in lyric beauty and shared love.

- Yumeji’s Theme whispers in silence and shadow.

- A raga or Persian melody blooms slowly, leaving room for inward meditation.

Romance, then, is a song the heart knows—but the world teaches us how to sing it.