ChatGPT:

🧠

The Deceived Brain: Why Your Mind Sees What Isn’t There

(Based on Alain Goriely’s “Coding and Illusion,” explained through neuroscience)

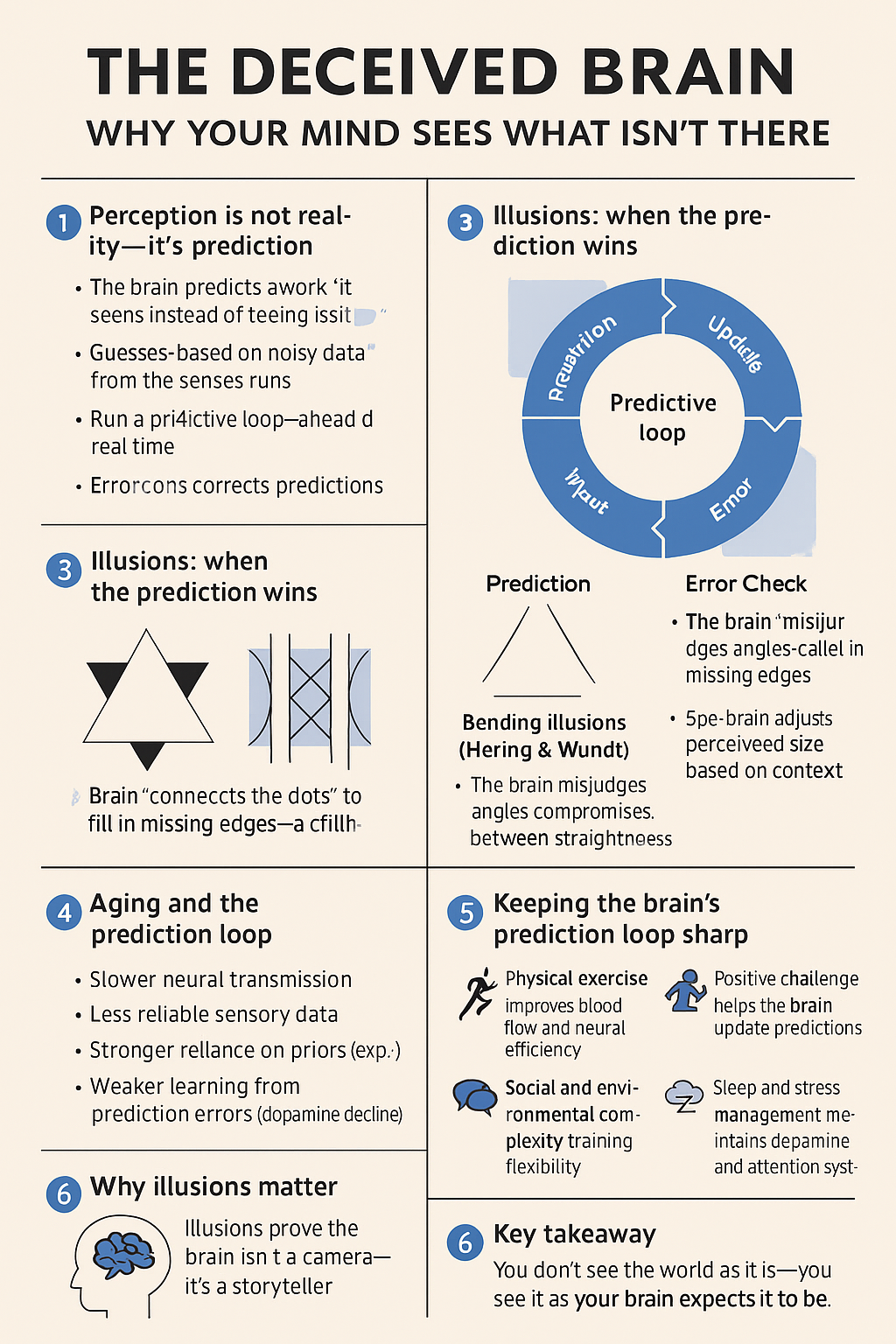

1. Perception is not reality — it’s prediction

- Your brain doesn’t see the world; it predicts it.

- It takes limited, noisy data from the senses and guesses what’s most likely out there.

- This process runs so fast (milliseconds ahead of real time) that perception feels instantaneous.

- The brain constantly updates its model:

- Predict → Compare → Correct → Repeat

- When the prediction fits the data, you see “reality.”

- When it doesn’t, you see an illusion.

2. What is “Coding and Illusion” about?

- Alain Goriely, a mathematician and neuroscientist, explores how visual illusions reveal how the brain encodes and predicts reality.

- Illusions aren’t mistakes — they’re evidence of how the visual system constructs meaning from partial data.

- Goriely uses mathematical models (curvature minimization, angle bias, size estimation) to explain why illusions occur and what they reveal about brain function.

3. The brain’s predictive loop in action

- Think of the brain as a Bayesian machine — it combines prior knowledge with new sensory input to make the best possible guess.

- Loop structure:

- Prediction: Brain expects certain sensory patterns based on experience.

- Input: Eyes, ears, skin send real-time data.

- Error Check: Brain compares data vs. prediction (prediction error).

- Update: Beliefs are adjusted to minimize error.

- This loop repeats constantly, keeping perception stable and fast.

- It’s like having an internal “autopilot” that predicts the world before it happens.

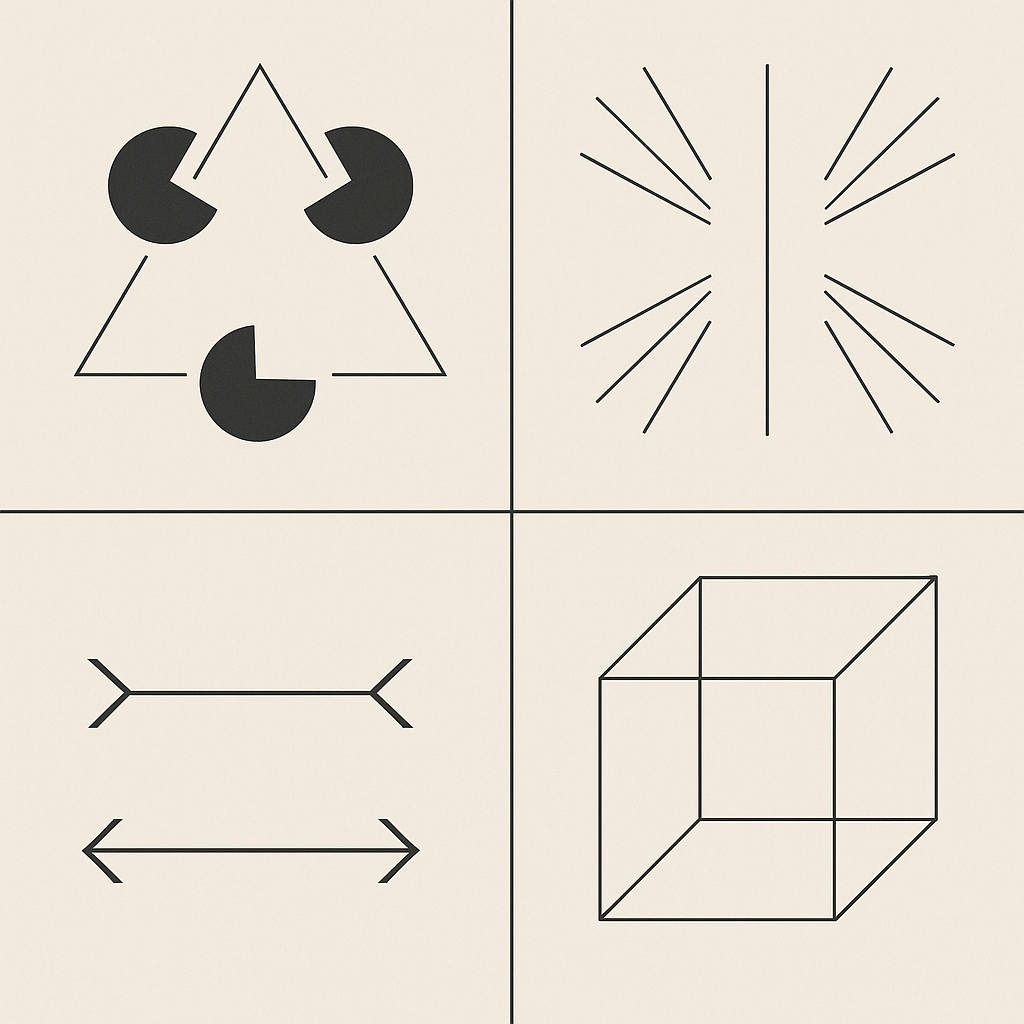

4. Illusions: when the prediction wins

a. Illusory contours (Kanizsa triangle)

- You see a bright triangle that isn’t drawn.

- The brain “connects the dots” using its rule of good continuation — edges should be smooth and complete.

- Neural circuits in the visual cortex fill in missing edges to make sense of the scene.

b. Bending illusions (Hering & Wundt)

- Straight lines look curved against radiating or converging backgrounds.

- The brain systematically misjudges angles (called Brentano’s law).

- The visual system compromises between straightness and context, producing the bowed effect.

c. Size illusions (Müller–Lyer)

- Two identical lines look different in length depending on their arrow tips.

- The brain interprets angles as depth cues.

- It adjusts perceived size based on context — like how things look smaller when “farther away.”

5. Gestalt psychology and modern neuroscience

- Early psychologists (Wertheimer, Köhler, Koffka) said:

“The whole is more than the sum of its parts.” - Goriely’s math proves that idea still holds.

- Gestalt principle: The brain perceives organized structures, not isolated features.

- Neuroscience version:

- Neurons in the visual cortex work in networks.

- Higher regions (V2, V4, IT) send feedback to lower regions (V1).

- Perception emerges from these interactions — relationships, not pixels.

- In short: perception is the brain’s best guess about what the parts mean together.

6. Aging and the prediction loop

- As we age, the predictive loop still works, but it slows and shifts.

- Changes that occur:

- Slower neural transmission (due to myelin loss).

- Less reliable sensory data (eyes, ears degrade).

- Stronger reliance on priors (experience, habits).

- Weaker learning from prediction errors (dopamine decline).

- Result:

- Older adults rely more on context and expectation.

- The brain favors stability over flexibility — still predictive, but more stubborn.

7. Keeping the brain’s prediction loop sharp

Research in gerontology and neuroscience shows you can preserve this system:

What helps:

- 🏃♂️ Physical exercise: Improves blood flow, myelin integrity, and neural efficiency.

- 🧩 Cognitive challenge: Learning new skills keeps the brain updating its predictions.

- 🗣️ Social and environmental complexity: Real-world unpredictability trains flexibility.

- 🎧 Good sensory input: Correct hearing or vision loss early — clearer data = better predictions.

- 😴 Sleep and stress management: Maintain dopamine and attention systems that encode prediction errors.

What research shows:

- Combined training (mental + physical) produces better results than either alone.

- Dopamine boosters (like L-dopa in studies) can temporarily restore learning and reward-based prediction in older adults.

- Curiosity and novelty act as natural “neural fertilizers,” helping maintain adaptability.

8. Why illusions matter

- Illusions prove the brain isn’t a camera—it’s a storyteller.

- Every perception is a negotiation between expectation and evidence.

- When that negotiation leans too far toward expectation, we see things that aren’t there.

- But this same mechanism allows art, imagination, and foresight — our ability to think beyond the present moment.

- Goriely’s work bridges math, psychology, and neuroscience to show that illusion is not failure—it’s function.

9. Key takeaway

Every illusion reminds us:

You don’t see the world as it is—you see it as your brain expects it to be.

The brain’s job is not to record the world but to predict it.

Illusions reveal how it does this: by continuously minimizing error, smoothing uncertainty, and filling gaps.

With age, the loop changes but doesn’t vanish—and with mental and physical activity, it can stay remarkably sharp.

The “deceived brain” is not broken; it’s creative.