ChatGPT:

⏱ The Evolving Second: How Humanity Redefined Time Itself

1.

Before We Had Clocks — Time as Nature’s Rhythm

- For most of human history, “time” meant sunrise, noon, and sunset.

- A “day” was one full spin of the Earth, and everything else was guesswork: shadows, sundials, water clocks, and candle marks.

- There was no standard “second.” Time was local, natural, and messy — people just lived by light and dark.

2.

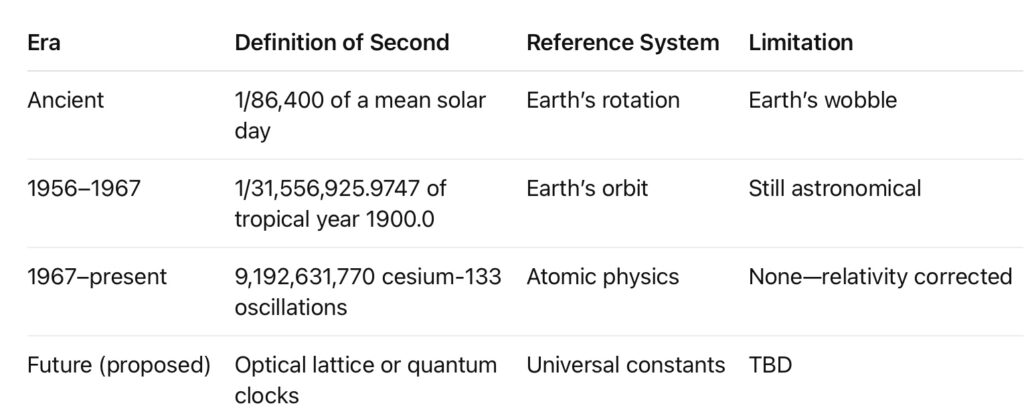

The Birth of the Second (Pre-1960): Earth as the Clock

- As mechanical clocks improved, scientists needed a smaller, universal slice of the day.

- They divided one mean solar day into:

- 24 hours,

- 60 minutes per hour,

- 60 seconds per minute.

- This made 1 second = 1/86,400 of a day.

- In theory, that seemed elegant — but in practice, the Earth isn’t a perfect timekeeper:

- Its rotation wobbles due to tides, earthquakes, shifting ice, and interactions with the Moon.

- Astronomers in the 1930s and 1940s noticed that the Earth’s spin wasn’t uniform.

- The “day” could vary by milliseconds — enough to throw off precision navigation and astronomy.

- Lesson learned: the planet is a wonderful home, but a terrible metronome.

3.

The First Fix: Measuring Time by the Sun’s Orbit (1956–1967)

- Scientists tried to anchor the second to something more stable than Earth’s rotation: the Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

- In 1956, the second was redefined as:

1/31,556,925.9747 of the tropical year 1900.0

(the length of one full seasonal cycle as measured at the start of the 20th century) - This was still astronomical, but less wobbly — orbital motion is smoother than daily spin.

- However, it still depended on Earth’s movement, and astronomers wanted something universal, measurable anywhere in the cosmos.

4.

The Atomic Revolution (Post-1967): Time by Quantum Physics

- The breakthrough came from atomic physics.

- Every atom of cesium-133 vibrates at a precise frequency when it flips between two energy states (a “hyperfine transition”).

- These vibrations are identical everywhere in the universe — perfect for defining time.

- In 1967, the International System of Units (SI) adopted this definition:

One second is the duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation emitted by a cesium-133 atom transitioning between two hyperfine levels. - Why this matters:

- No dependence on the Earth, Sun, or any celestial body.

- Immune to weather, geography, and political borders.

- Identical whether you’re in Paris, on Mars, or in interstellar space.

- Humanity’s clock was no longer tied to spinning rocks — it was tied to the fundamental physics of the universe.

5.

Precision Meets Relativity: The Second Isn’t Always Equal Everywhere

- The atomic second is absolute by definition — but time itself is relative.

- According to Einstein’s theories:

- Special relativity → A moving clock ticks slower relative to a stationary one.

- General relativity → A clock in stronger gravity ticks slower than one in weaker gravity.

- So, even though both use cesium, two clocks in different environments disagree on how many seconds have passed.

- Examples:

- A clock at sea level runs slightly slower than one on top of Mount Everest (gravity weaker at altitude).

- GPS satellites orbit higher up, where gravity is weaker, so their clocks tick faster — but they’re also moving fast, which slows them down. Engineers compensate for both effects every day.

- Astronauts aboard the International Space Station experience both effects — net result: their clocks run about 10 microseconds per day slower than Earth’s.

6.

The Second Beyond Earth: Space and Time in Deep Space

- Far from Earth, the same cesium rule applies — but relativistic corrections are critical.

- Voyager 1 and 2, now billions of kilometers away, have clocks that tick at slightly different rates:

- Their speed (~17 km/s) slows their clocks by about 0.05 seconds per year relative to Earth (special relativity).

- Being far from the Sun’s gravity speeds them up by roughly the same amount (general relativity).

- The effects nearly cancel out, but NASA tracks both precisely through signal analysis and software corrections.

- All deep-space missions synchronize their signals to Earth’s atomic time, converting everything into a unified “solar system time” (Barycentric Dynamical Time).

- The spacecraft’s clocks don’t change — our mathematics adjusts for physics.

7.

Time on Other Worlds: Mars and Beyond

- A day on Mars (a sol) is 24 h 39 m 35 s — about 39½ minutes longer than an Earth day.

- Colonists will likely use Mars Coordinated Time (MTC) for civil life, defining “noon” by the Sun overhead just like Earth days.

- Physically, Mars clocks tick slightly faster than Earth clocks:

- Gravity is weaker (0.38 g) and Mars is farther from the Sun.

- The result is roughly 0.34 milliseconds faster per Earth day.

- Over a decade, that adds up to about 1.25 seconds ahead of Earth.

- Software would automatically adjust for these effects in communications, navigation, and finance between planets.

- For humans on Mars, the difference is unnoticeable — but for engineers, it’s vital.

8.

Why the Redefinition Matters

- Each redefinition of the second reflects our evolving understanding of physics and precision:

- From observing the sky → to measuring orbital motion → to using atomic transitions.

- The shift represents our journey from macroscopic time (celestial motion) to microscopic time (quantum physics).

- Today’s atomic clocks are so stable that they’d drift less than a second over the age of the universe.

- Future redefinitions may tie the second to even more fundamental constants, like the vibrations of optical transitions or quantum entanglement.

9.

In One Sentence

Humanity began counting time by watching the sky — but ended up counting it by listening to atoms.

10.

Key Takeaway Table

Final Thought:

From sundials to cesium atoms, each step in redefining the second marks a triumph of understanding — a move from watching nature to mastering nature’s constants. The second today is not just a unit of time; it’s a symbol of humanity’s precision in measuring the universe itself.