Gemini:

The Geometry of Duty: Particularism, Universalism, and the Ethics of Proximity

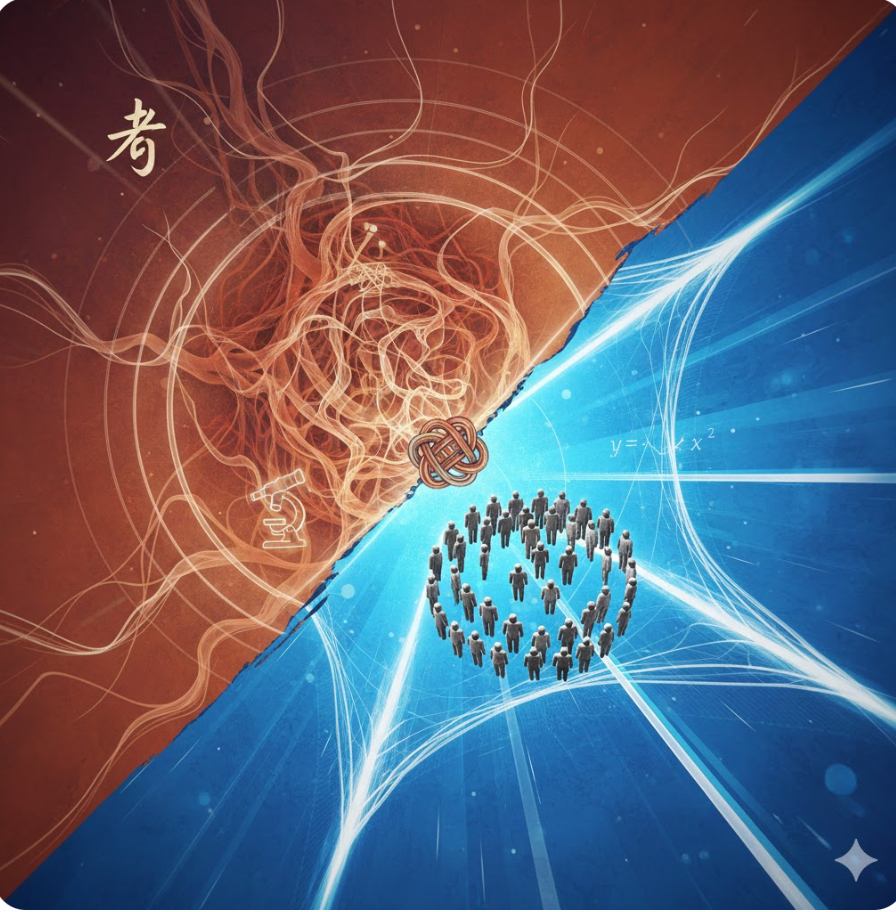

One of the most enduring tensions in moral philosophy is the conflict between the “Ethics of the Near” and the “Ethics of the Far.” It is a battle between two distinct geometries of duty: Particularism, which suggests our moral obligations are concentrated on those with whom we share history and blood; and Universalism, which argues that morality requires an impartial view where every human life holds equal weight. When we debate the value of looking after aging parents versus volunteering for the broader society, we are not merely discussing time management; we are navigating the fault lines between these two ancient intellectual traditions.

The Eastern Dialectic: The Root vs. The Sun

In classical Chinese philosophy, this tension creates a sharp divide between Confucianism and Mohism. The Confucian tradition champions Graded Love (Ai You Cha Deng), positing that benevolence is not a flat plane but a ripple. Confucius argued that moral development is organic: it must begin at the “root”—filial piety (Xiao) toward one’s parents—before it can extend to the branches of the community. To the Confucian, a morality that skips the family to serve the state is an unnatural abstraction. It is attempting to harvest fruit from a tree with severed roots.

In stark contrast, the Mohist school, led by Mozi, advocated for Impartial Love (Jian Ai). Mozi argued that the root of social chaos—war, corruption, nepotism—is the very partiality that Confucians celebrate. If one prioritizes their own father over a stranger’s father, conflict is inevitable. For the Mohist, the moral ideal is akin to the sun: it shines on all equally, without preference for the “near.” From this perspective, devoting oneself entirely to the private care of one parent is a misallocation of resources, as that energy could theoretically relieve the suffering of many in the public sphere.

The Western Dialectic: The Calculus vs. The Bond

A similar fracture runs through Western thought. Utilitarianism, most famously articulated by thinkers like Peter Singer, acts as the modern heir to Mohism. It relies on a “moral calculus”: an action is judged by its ability to maximize aggregate well-being. From a strict utilitarian perspective, spending years acting as a full-time caregiver for a single terminal individual is inefficient if that same individual could generate greater utility by working, earning, and donating to save multiple lives. This view challenges us with the uncomfortable question: Does biological proximity or emotional history justify weighing one life more heavily than another?

Opposing this is the Ethics of Care, a framework often associated with feminist philosophy and thinkers like Nel Noddings. This school rejects the “geometric” view of morality as cold and abstract. It argues that moral life is situated in relationship, not calculation. The value of caregiving lies in the irreplaceability of the actors. To the state, an elderly patient is a statistic; to the caregiver, they are a specific narrative. The duty to the “nearest” is not a bias to be overcome, but the fundamental substance of morality itself. To abandon the specific Other in the name of the “General Good” is to hollow out the very humanity that society is meant to protect.

Sociology and the Definition of Contribution

When we translate these philosophies into modern sociology, the debate shifts to the definition of “social contribution.” Modern society, driven by market logic, often adopts a “GDP view” of worth: contribution is measured by what is visible, scalable, and public. Volunteering for an NGO or holding a title in a civic organization constitutes “Bridging Capital”—it connects groups and is publicly celebrated.

However, this metric often ignores “Bonding Capital”—the intense, invisible labor that sustains the primary unit of society: the family. Sociologically, the family is the first line of defense against state collapse. When an individual assumes the burden of care for the elderly, they are internalizing a massive social cost. Conversely, the individual who neglects private duties to pursue public recognition may be viewed as a “moral free rider”—garnering the prestige of public service while externalizing the difficult, unglamorous care of their kin onto the state or the community.

The Synthesis: Differentiating the Heart

The resolution of this conflict may lie in the Stoic concept of Oikeiosis, or “appropriation.” The Stoics visualized duty as concentric circles—self, family, community, humanity. The goal is not to abandon the inner circles for the outer ones, nor to ignore the outer for the inner, but to ensure the integrity of the core so that it may sustain the whole.

True social contribution, therefore, is not a binary choice between the private and the public. It is a recognition of sequential duty. The “private” work of caregiving—preserving the dignity of the dying, maintaining the continuity of memory in dementia—is the training ground for the “public” virtues of patience and empathy. To disparage the private sphere in favor of the public is to misunderstand the architecture of civilization. A society that celebrates the “Universal” while allowing the “Particular” to rot in neglect is a society with a shiny façade and a crumbling foundation. The ethics of the future must recognize that the hand that sustains the one is as vital as the voice that speaks for the many.