ChatGPT:

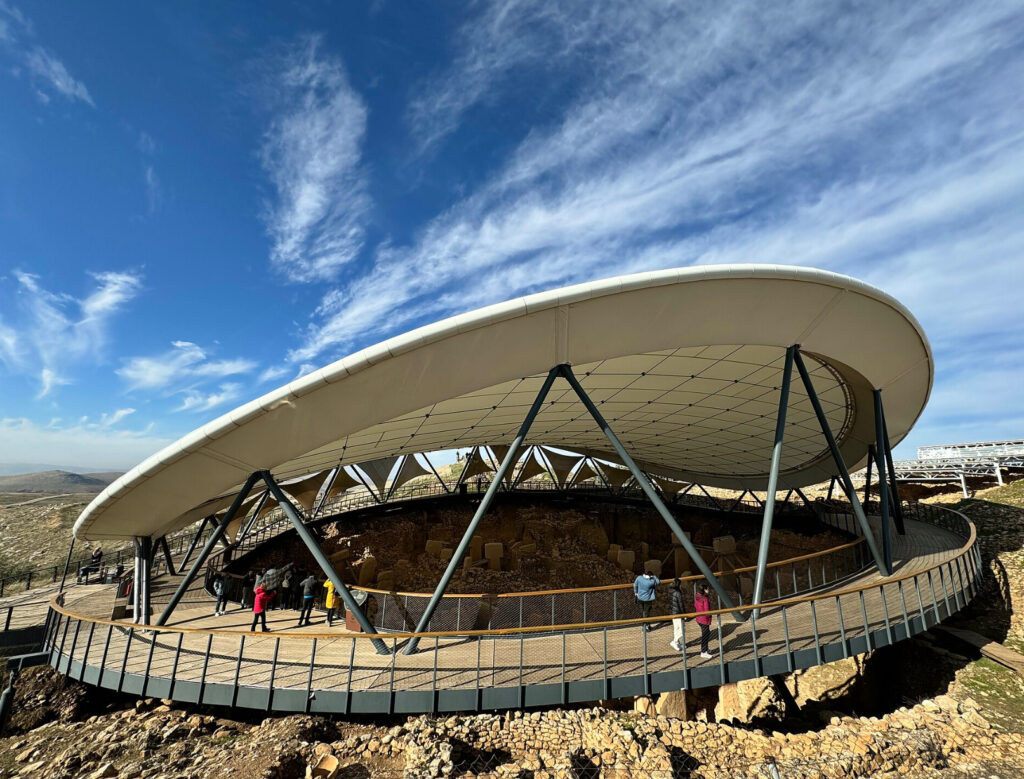

Göbekli Tepe, located near Şanlıurfa in southeastern Turkey, is one of the most significant archaeological sites in the world. It is a Neolithic sanctuary dating back to around 9600 BCE, making it over 11,000 years old and older than Stonehenge or the Great Pyramids.

Key Features:

1. Architecture:

• The site consists of circular and oval structures with large T-shaped limestone pillars, some standing up to 6 meters (20 feet) tall.

• These pillars are intricately carved with reliefs of animals, abstract symbols, and human-like figures.

2. Purpose:

• Göbekli Tepe is believed to be a ceremonial or religious site, possibly the world’s oldest known temple.

• It shows no signs of permanent settlement, such as domestic buildings, suggesting it was used by hunter-gatherers for rituals.

3. Construction and Society:

• The sophistication of Göbekli Tepe’s construction challenges previous assumptions about early human societies.

• It indicates that complex religious or communal practices predated the development of agriculture, suggesting that such activities may have contributed to the shift towards settled life.

4. Rediscovery and Excavation:

• The site was rediscovered in the 1960s but properly excavated starting in the 1990s by German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt.

• Many of the structures remain buried, and ongoing excavations continue to provide new insights.

5. Cultural and Symbolic Significance:

• The carvings feature animals like foxes, snakes, wild boars, and birds, representing the symbolic and spiritual world of the people who built the site.

• Its construction demonstrates remarkable organizational skills, especially for a pre-agricultural society.

Göbekli Tepe is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and remains a key location for understanding the origins of human civilization, social organization, and religious practices.

Göbekli Tepe was first identified as a significant archaeological site through a series of rediscoveries and reevaluations spanning decades:

1. Initial Discovery (1963):

• The site was initially noted during a joint survey by Istanbul University and the University of Chicago.

• Researchers observed some limestone slabs and scattered flint tools on the surface of the hill but mistook them for the remains of a Byzantine cemetery or a medieval site.

• Due to this misclassification, no further investigations were conducted at the time.

2. Reevaluation (1994):

• In 1994, German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt, who had been working on nearby sites, came across a mention of Göbekli Tepe in earlier survey reports.

• He visited the site and immediately recognized the significance of the T-shaped pillars visible on the surface, realizing they were far older than previously thought.

3. Start of Excavations (1995):

• Klaus Schmidt began excavations in collaboration with the German Archaeological Institute and the Şanlıurfa Museum.

• The work revealed that the site was not a burial ground but a complex of monumental structures built by Neolithic hunter-gatherers.

4. Surface Evidence:

• Initial surface findings included flint tools, fragments of limestone carvings, and the tops of buried pillars.

• The lack of pottery and other domestic artifacts suggested the site’s ceremonial purpose, leading to its reinterpretation as one of the oldest known temples.

Schmidt’s meticulous work at Göbekli Tepe transformed our understanding of prehistoric societies, proving that monumental architecture was within the capabilities of hunter-gatherers and reshaping theories about the origins of civilization.

Archaeologists concluded that Göbekli Tepe was built by a hunter-gatherer society through a combination of evidence from the site itself and its broader historical context. Key factors supporting this theory include:

1. Absence of Agriculture or Permanent Settlements:

• No evidence of farming or domesticated animals was found at Göbekli Tepe.

• The people who built it likely relied on hunting wild animals and gathering plants, as indicated by tools and remains found at the site.

• Archaeologists found no permanent housing structures, storage facilities, or agricultural tools, which are hallmarks of a settled, farming-based society.

2. Dating of the Site:

• Radiocarbon dating places Göbekli Tepe at around 9600 BCE, in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, before the advent of widespread agriculture in the region.

• This predates other known examples of settled farming communities and suggests the builders were still living a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle.

3. Stone Tools and Artifacts:

• The discovery of flint tools, such as blades and arrowheads, is consistent with hunter-gatherer societies.

• These tools suggest that the people at Göbekli Tepe hunted animals in the surrounding region.

4. No Domestic Waste:

• Archaeologists found very few domestic artifacts, such as pottery, cooking hearths, or food storage items, which are typically associated with sedentary communities.

• This suggests that the site was not a residential area but a ceremonial or ritualistic center.

5. Organization of Labor:

• The construction of Göbekli Tepe required significant labor and coordination, indicating that even mobile hunter-gatherer groups could organize large-scale projects.

• Seasonal gatherings for rituals or construction could have provided the opportunity to mobilize these efforts.

6. Animal and Plant Remains:

• The site yielded bones of wild animals, such as gazelle, boar, and birds, indicating that the diet of the builders was based on hunting rather than animal husbandry.

• Similarly, there is no evidence of cultivated grains or other crops, but wild plant remains suggest foraging.

7. Hunter-Gatherer Social Complexity:

• Göbekli Tepe challenges the traditional view that social complexity only arises after the advent of agriculture.

• The site demonstrates that even hunter-gatherer societies could create monumental architecture and complex rituals, reshaping our understanding of their capabilities.

By synthesizing these lines of evidence, archaeologists concluded that Göbekli Tepe was built by advanced hunter-gatherers during a transitional period before the emergence of agricultural societies. This discovery has prompted a rethinking of the relationship between monumental construction, social organization, and the origins of farming.