ChatGPT:

Bath is a historic city in Somerset, England, best known for its natural hot springs, elegant Georgian architecture, and storied past as a center of leisure and refinement. Its origins lie deep in antiquity, with human activity around its thermal waters traced back to the Iron Age, well before the Roman occupation of Britain.

Origins and Roman Influence:

The hot mineral springs—unique in Britain—first attracted attention from local Celtic tribes who viewed the site as sacred. With the Roman conquest of Britain in the first century AD, the settlement, then known as Aquae Sulis, took shape around the springs. The Romans constructed a grand temple dedicated to the goddess Sulis Minerva, as well as an elaborate bathing complex and social center that drew visitors from across the empire. Built around a remarkable system of stone-lined reservoirs and lead pipes, the Roman Baths combined therapeutic bathing rituals with religious devotion, firmly establishing Bath’s reputation as a place of healing and relaxation. The Roman city thrived for several centuries, its architecture and engineering prowess evident in the structures and artifacts that survive to this day.

Medieval and Early Modern Developments:

Following the Roman withdrawal in the early fifth century, Aquae Sulis fell into decline, gradually transforming into a modest Anglo-Saxon settlement. During the medieval period, monastic communities revitalized Bath’s importance, with the founding of Bath Abbey—a place of Christian worship standing in some form since the 7th century. By the Middle Ages, Bath was a moderately prosperous market town, and its thermal springs continued to attract visitors for their supposed curative powers. Pilgrims, gentry, and local residents made use of rudimentary bathing facilities. Over time, the town’s reputation as a therapeutic destination grew, aided by royal patronage and interest in the “healing waters.”

The Georgian Golden Age:

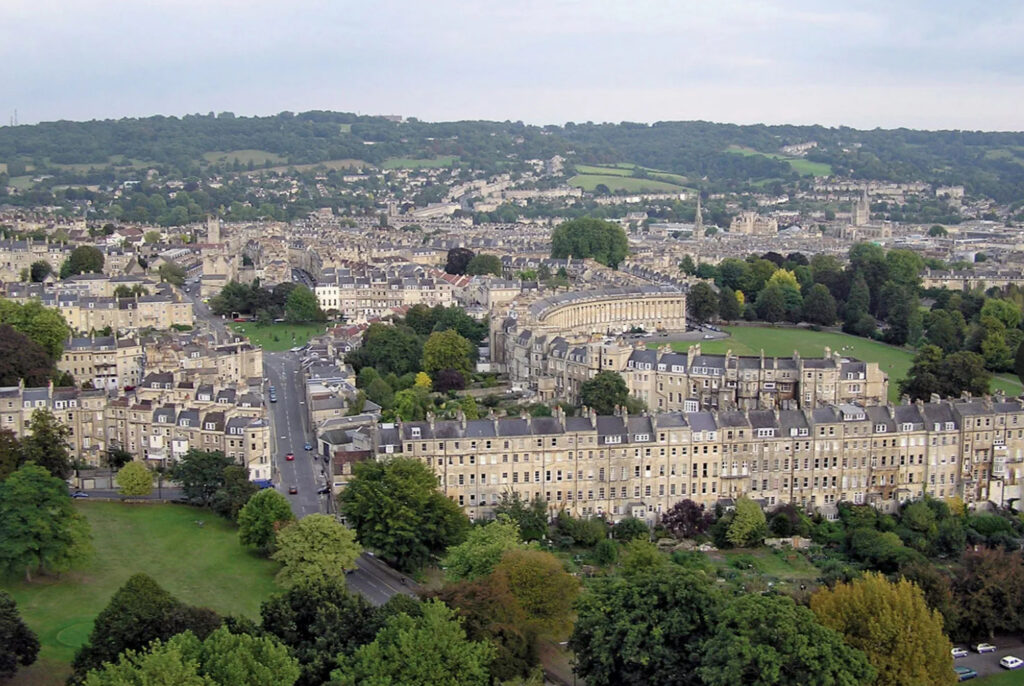

Bath’s most transformative era came in the 18th century, a time often referred to as its “Golden Age.” Spurred by wealthy and fashionable visitors seeking the social scene and medicinal waters, the city underwent extensive urban redevelopment. Visionary architects and planners, including John Wood the Elder, John Wood the Younger, and later Thomas Baldwin, reshaped Bath into a paragon of Georgian elegance. They employed locally quarried honey-colored Bath Stone to create harmonious crescents, squares, and terraces. Landmark ensembles such as the Royal Crescent and the Circus epitomized refined neoclassical design, while communal assembly rooms and pleasure gardens facilitated the era’s lavish social life. The city’s appeal was such that prominent figures, including literary icons like Jane Austen, spent part of their lives here, immortalizing Bath’s genteel society in their works.

19th and Early 20th Centuries:

As the 19th century progressed, Bath gradually adapted to changing tastes and the rise of other fashionable spas. Advancements in medicine and a shift away from “taking the waters” for health reasons moderated its fame as a spa resort. Nonetheless, the city remained a desirable place to live and visit. Industrialization largely bypassed Bath, helping preserve its architectural heritage but also limiting economic growth compared to more industrially driven cities.

Modern Bath and Preservation Efforts:

The 20th century brought concerted efforts to protect and restore Bath’s unparalleled Georgian landscape. Post-World War II redevelopment, at times controversial, gradually gave way to strong preservation movements. In 1987, the city was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognizing its outstanding universal value as a place shaped by Roman remains, Georgian architecture, and a cultural tradition of health and leisure.

Continuity and Character:

Contemporary Bath seamlessly merges the old and the new. Visitors can still experience the legacy of Aquae Sulis at the meticulously preserved Roman Baths, soak in the same geothermal waters at the modern Thermae Bath Spa, and stroll through pristine streets lined with Georgian terraces that remain private homes, boutique hotels, and cultural institutions. Alongside these historical treasures, Bath nurtures a lively arts scene, dynamic restaurants and cafés, annual festivals, and a strong sense of community. All of this reflects a city that, from its ancient origins to its modern identity, has continually drawn people to its storied springs and distinctive charm.

Bath’s literary culture flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, fueled by its elegant social scene and numerous venues for reading and discussion. Circulating libraries, book clubs, and salons brought together residents and visitors who came to the city for its healing waters and fashionable gatherings. Reading was as much a pastime as attending balls or concerts, allowing literature to blend seamlessly into Bath’s refined social life.

Jane Austen’s association with the city is among its most celebrated literary connections. She lived in Bath between 1801 and 1806, encountering a society layered with class distinctions, polite manners, and romantic expectations. This environment shaped her perceptions and found expression in her novels. Austen set parts of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion in Bath, using the city’s streets, Assembly Rooms, Pump Room, and promenades as both setting and social laboratory. In Northanger Abbey, Bath emerges as a place where a young heroine must learn to see through literary clichés and social pretenses. In Persuasion, it is more introspective, highlighting tensions between genuine feeling and the pressure to conform. Through these works, Austen revealed Bath’s dual nature: beautiful and sophisticated, yet often constrained by rigid codes of behavior and appearances.

Following Austen’s era, Bath continued to nurture a literary climate. Over the centuries, poets, essayists, and travel writers have been drawn to its architectural grandeur, cultural life, and layered history. Today, festivals, museums, and institutions like the Jane Austen Centre honor this legacy. Visitors can immerse themselves in the world Austen knew, engaging with readings, tours, and themed events that celebrate both her literary achievements and the city’s enduring role in shaping English literature. In this way, Bath remains inseparable from its storied literary traditions, continuing to inspire writers and readers alike.

The Georgian architecture and urban planning of Bath represent one of the most harmonious and comprehensive expressions of 18th-century design in Britain. During the Georgian era, the city underwent a transformative period of building and planning, largely influenced by visionaries such as John Wood the Elder, John Wood the Younger, and other prominent architects. They drew upon Palladian and neoclassical principles, embracing symmetry, proportion, and order to create a unified aesthetic that set Bath apart from other towns of its time.

Key elements such as the Circus (1754–1768) and the Royal Crescent (1767–1775) demonstrate how architects designed entire streetscapes as cohesive ensembles, rather than isolated buildings. Both masterpieces were constructed from locally quarried, golden-hued Bath Stone and incorporated classical motifs—columns, pediments, and decorative friezes—on their façades. In these grand crescents, rows of uniform townhouses curve gracefully around green spaces, blending urban living with elegant parkland in a way that was innovative for its day.

Today, the significance of Bath’s Georgian legacy endures. Its distinct architectural character, beautifully preserved streets, and carefully planned avenues earned it UNESCO World Heritage status. The city’s Georgian fabric reveals much about the ideals of the Enlightenment—harmony, reason, civic pride—while serving as a living museum of 18th-century urban design. In Bath, Georgian architecture and planning continue to inform modern preservation efforts and shape the character of a city celebrated worldwide for its timeless elegance.

Major Historical Monuments:

• Roman Baths (1st century AD): Ancient Roman bathing complex and temple dedicated to Sulis Minerva.

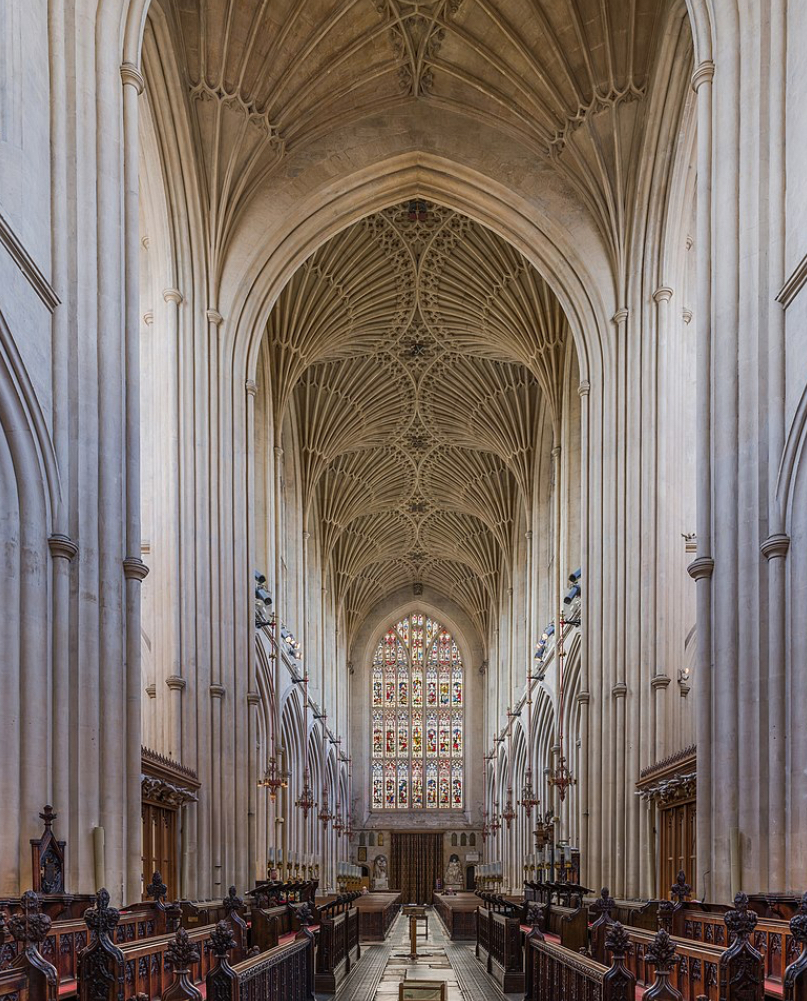

• Bath Abbey (established 7th century, rebuilt 12th–16th centuries): A Gothic church renowned for its fan vaulting and stained glass.

• The Royal Crescent (1767–1775): A grand semicircular row of Georgian townhouses designed by John Wood the Younger.

• The Circus (1754–1768): Three segments of curved Georgian façades by John Wood the Elder, forming a perfect circle.

• Pulteney Bridge (1769–1774): A Palladian-style bridge lined with shops, inspired by Florence’s Ponte Vecchio.

• Pump Room (1795): An elegant social space for Georgian visitors, adjacent to the Roman Baths.

Museums:

• Holburne Museum (founded 1882): Art and decorative arts housed in a former hotel turned gallery.

• Jane Austen Centre: A cultural exhibit celebrating Austen’s life in Bath and the Regency era.

• Victoria Art Gallery (opened 1900): Showcases historical and contemporary art collections.

• No. 1 Royal Crescent: A restored Georgian townhouse museum illustrating 18th-century domestic life.

• Herschel Museum of Astronomy: The former home of astronomer William Herschel, who discovered Uranus here.

Local Tourist Attractions:

• Thermae Bath Spa: Modern spa offering rooftop thermal baths with panoramic city views.

• Royal Victoria Park: Landscaped parkland near the Royal Crescent, ideal for picnics and strolling.

• Assembly Rooms (1771): Elegant Georgian social venue, historically used for balls and gatherings.

• Sally Lunn’s Historic Eating House: Home of the famous Sally Lunn Bun, a Bath specialty.

• Kennet and Avon Canal: Scenic towpaths for walking, cycling, and boat trips.

• Prior Park Landscape Garden: A picturesque 18th-century garden with sweeping views of the city.

Morning (9:00 AM – 12:00 PM):

Start your day with breakfast at Sally Lunn’s Historic Eating House, where you can try the famous Sally Lunn Bun—light, delicate, and perfect with butter or jam. Afterward, walk a few steps to Bath Abbey and enjoy its Gothic architecture and fan vaulting. Next, head to the Roman Baths as soon as they open to avoid crowds. Explore the ancient bathing complex and the museum’s exhibits that detail life in Roman Aquae Sulis.

Late Morning Coffee Break (Around 11:30 AM):

If time permits, stop for a quick coffee at a nearby café like Colonna & Small’s, which offers specialty brews to recharge before continuing your tour.

Early Afternoon (12:00 PM – 2:30 PM):

Cross Pulteney Bridge for scenic views and wander toward your chosen museum—No. 1 Royal Crescent, a restored Georgian townhouse illustrating 18th-century domestic life. After exploring the museum, head to a traditional pub such as The Raven for lunch. Try a local pie and a Bath Ale or Somerset cider for an authentic regional flavor.

Afternoon (2:30 PM – 5:00 PM):

Stroll through the elegant Georgian streets to admire The Circus and Royal Crescent, taking in the city’s signature architecture. Relax in Royal Victoria Park with a Bath Bun in hand, picked up from a bakery en route, for a sweet afternoon treat.

Evening (5:00 PM onwards):

End the day with an early dinner at a classic British restaurant like The Marlborough Tavern, known for using local, seasonal ingredients. Sample regional dishes—perhaps roast lamb or fresh fish—and raise a glass of locally produced cider to toast your one-day Bath adventure. If time remains, enjoy a leisurely stroll back toward the city center, soaking in the atmosphere before departing.