ChatGPT:

The Dark Side of the Moon: An Album Beyond Its Time and the Scholarly Obsession with Its Meaning

Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, released in 1973, occupies a singular position in the history of popular music, not simply because it sold over 45 million copies but because it has been relentlessly analyzed, dissected, and mythologized. From musicologists to cultural theorists, scholars have devoted countless pages to explaining why this particular forty-three minutes of sound continues to resonate across generations. The album is often framed as a rare convergence of commercial success, sonic innovation, and philosophical ambition—qualities that make it an irresistible object of academic fascination.

At its core, The Dark Side of the Moon is a “concept album,” a term applied to works unified by overarching themes or narratives rather than simply being collections of unrelated songs. Professor Milton Mermikides, in his 2025 lecture “Illuminating the Dark Side of the Moon,” traces the lineage of this idea back to Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads and Frank Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours, but he argues that Pink Floyd elevated the form to new heights. Unlike earlier attempts that relied mainly on lyrical unity, The Dark Side weaves together musical motifs, reprises, seamless segues, and a deliberate absence of traditional song breaks. The heartbeat that begins and ends the album is not merely a clever gimmick but a metaphor for the inescapable cycles of existence. According to Mermikides, this structural coherence situates the album as a quintessential expression of the “macro-level cohesion” that defines the concept album genre.

Academics have long been drawn to the album’s lyrical content, which addresses themes so universally resonant that they have been described as a modern Book of Ecclesiastes. Roger Waters’ words touch on the passage of time (“Time”), the futility of greed (“Money”), the fragility of sanity (“Brain Damage”), and the inevitability of death (“The Great Gig in the Sky”). Scholars such as Peter Rose have argued that the lyrics’ power lies precisely in their familiarity: they recycle ancient philosophical anxieties. In this reading, the album doesn’t offer answers; instead, it holds up a mirror to the listener’s own dread and wonder. Mermikides links these lyrics to Mark Twain’s observation that every person is a moon with a dark side never revealed, and to Carl Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious—a repository of shared human fears and desires. This resonance with archetypal ideas helps explain why the album is so frequently described as “timeless.”

But if the lyrics provide the philosophical scaffolding, it is the music itself that gives the album its emotional and intellectual force. Pink Floyd fused traditional rock instruments with the then-novel possibilities of electronic sound. Mermikides emphasizes that their use of tape loops, synthesizers, and multi-track recording created what he calls a “sonic tapestry of time and space.” For example, in “On the Run,” a simple sequence programmed into an EMS Synthi AKS synthesizer transforms into a pulsing, unsettling soundscape that evokes both technological anxiety and existential urgency. The now-iconic cash register sounds in “Money” and the disorienting clocks in “Time” are examples of the band’s innovative approach to studio-as-instrument, an approach that scholars of electronic music—such as Thom Holmes—cite as pivotal in legitimizing the studio itself as a compositional tool.

Another area of academic attention has been the album’s harmonic language. In popular music, harmonic complexity is often subordinated to accessibility, but Pink Floyd frequently defied this convention. Mermikides meticulously catalogues their use of unusual chords and modal mixtures, such as the Emadd9 that opens “Breathe,” the shifting tonal centers of “The Great Gig in the Sky,” and the ambiguous Dorian mode of “Any Colour You Like.” He notes that such harmonies create a sense of uncertainty and magic, a feeling of unresolved tension that mirrors the album’s lyrical preoccupations. These harmonic choices are not simply decorative; they are integral to the work’s impact, providing what Mermikides calls “prediction-thwarting,” an experience of surprise that keeps listeners engaged and emotionally vulnerable.

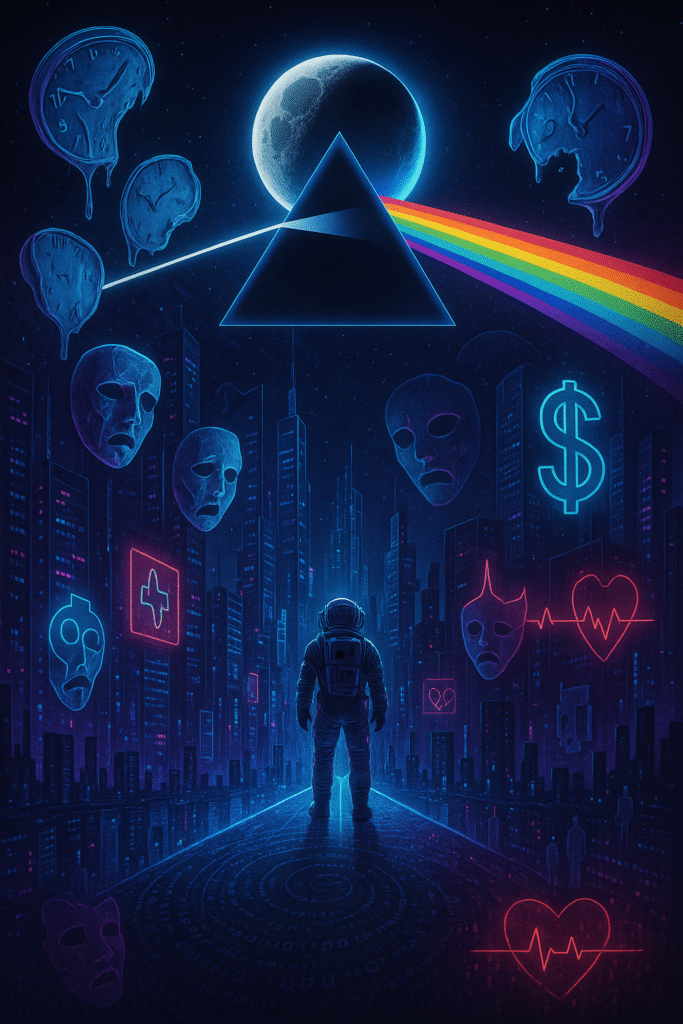

Equally important is the album’s visual presentation. The cover art—a prism refracting a beam of white light into a rainbow—has been subject to endless interpretation. Some critics see it as a symbol of enlightenment and fragmentation; others read it as a commentary on perception itself. The decision to exclude the band’s image from the cover was radical in 1973 and underscored the idea that the work should be experienced as a unified statement rather than a commercial product. Scholars in cultural studies, such as Eilon Wolfson, have argued that the artwork completes the album’s conceptual framework by visually representing the themes of division, transformation, and hidden complexity.

Beyond musicology, the album has inspired discussions in sociology, psychology, and even political theory. The track “Us and Them” has been read as an indictment of war and class division, resonating with Wilfred Owen’s First World War poetry. Others have interpreted the album as an allegory for Syd Barrett’s mental decline, a cautionary tale about the costs of fame and creativity. In this sense, The Dark Side of the Moon functions as both a personal confession and a universal parable.

In contemporary scholarship, the album is increasingly discussed in the context of digital reproduction and streaming culture. As Anne Danielsen points out in her work on musical rhythm in the digital age, albums like The Dark Side of the Moon challenge the atomization of music into playlists and single tracks. Its seamless transitions and cumulative narrative are best appreciated as an uninterrupted experience—an experience that is becoming harder to maintain in the era of algorithmic listening.

Ultimately, what makes The Dark Side of the Moon a perennial subject of academic interest is that it resists easy categorization. It is at once an artifact of 1970s progressive rock and a meditation on timeless human concerns. It is both a technical triumph and an emotional confession. It is a commercial juggernaut and an avant-garde experiment. This multiplicity is why scholars keep returning to it, finding new resonances with each generation. To borrow Mermikides’ metaphor, the album is a prism: a simple shape that refracts endless colors, revealing the hidden spectrum of human experience.