ChatGPT:

⸻

Point and Line to Plane by Wassily Kandinsky

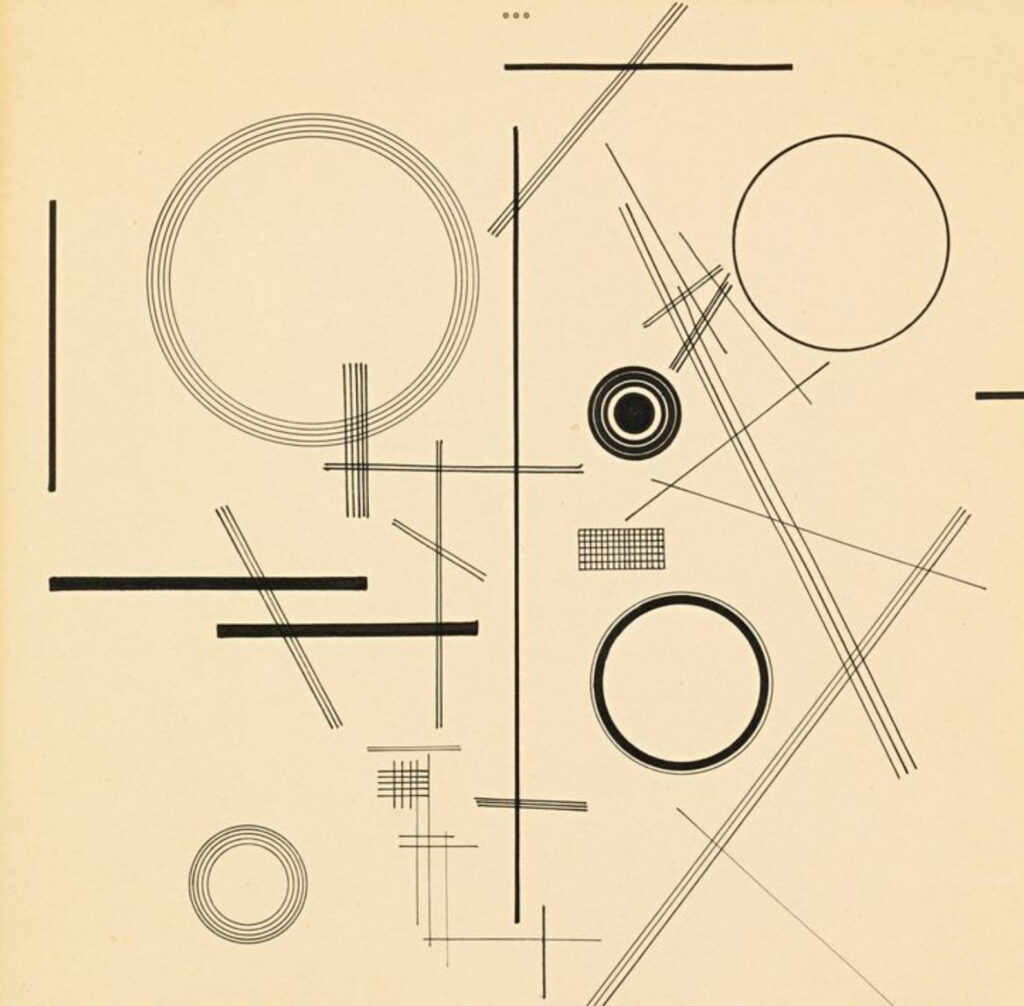

This foundational text in modern art theory, written by Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky in 1926, explores the metaphysical and psychological properties of geometric forms—specifically the point, the line, and their evolution into the plane. Through a synthesis of visual art, music, and spirituality, Kandinsky builds a visual grammar that supports abstract painting as a language capable of expressing inner emotion and universal truths.

⸻

🧠 Conclusion (Resumen)

Kandinsky’s Point and Line to Plane is a deeply theoretical investigation that links geometry to spirituality and art. He starts with the point as the minimal visual element, attributing to it not only spatial but also temporal and tonal properties—comparing it to a sound or musical note. Lines arise from moving points, and he distinguishes between straight, curved, and angular lines, each carrying expressive values. Planes are formed through line interactions, and their composition mirrors symphonic arrangements in music. Kandinsky emphasizes the inner necessity—the artist’s need to express spiritual truths through abstract forms. His system provides a visual syntax where form, color, and rhythm interact to awaken emotion and consciousness. Ultimately, the work argues for the autonomy of abstract art, validated not by representation but by resonance and form dynamics.

⸻

🔑 Key points (Puntos clave)

🎯 Point as origin: The point is the foundational graphic element, akin to a silence or musical note in a composition.

🎼 Temporal symbolism: Kandinsky interprets shapes with rhythmic and tonal qualities, suggesting art is as temporal as it is spatial.

📏 Line from movement: A line emerges from a point in motion—horizontal is cold and passive, vertical is warm and active.

🎢 Angle expression: Angles and directionality are emotionally expressive; acute angles are aggressive, obtuse are passive.

🎨 Planes as composition: The interaction of lines creates planes, whose layout represents the balance and dynamism of a composition.

🧭 Internal tension: Each form contains intrinsic forces that produce psychological effects, like tension and release.

🌀 Color as tone: Though less emphasized than in Concerning the Spiritual in Art, color still plays a vital tonal role in form interaction.

🗣 Abstract language: The work asserts abstract forms can communicate as precisely as words or music.

🔥 Inner necessity: True art stems from a spiritual impulse within, not from imitation of external reality.

🌌 Spiritual geometry: Geometry isn’t merely technical—it’s a medium to channel cosmic and psychological truth.

⸻

📘 Summary (Resumen)

1. Kandinsky begins by defining the point as the smallest possible visual unit. It is both spatially static and emotionally neutral, yet pregnant with potential, similar to a note in music.

2. A line results when a point moves in any direction. This act of movement introduces energy, tension, and expressivity to the artwork.

3. Different line orientations carry different psychological weights: horizontal lines suggest calm, vertical ones suggest growth, and diagonal ones embody conflict or instability.

4. The plane is formed by the interplay of lines. It is the space where artistic compositions come alive, structured like a musical symphony with rhythm and tension.

5. Angles created by line intersections are expressive tools: sharp angles may indicate aggression, while wide angles evoke openness or tranquility.

6. Kandinsky introduces the idea of form resonance, where the shape alone, even without color, can stir emotional reactions.

7. The principle of inner necessity underscores that true art must arise from the inner spiritual drive of the artist, not mimicry of nature.

8. While color is touched upon, this work focuses more on formal relationships—how elements like lines and shapes communicate independently of hue.

9. Kandinsky draws parallels between painting and music, proposing that visual art can be composed like a musical piece, with formal elements playing the role of notes and harmonies.

10. Ultimately, the book defends abstraction as a universal language, capable of expressing emotional and spiritual truths that figurative art cannot.

Quotes from

Point and Line to Plane

by Wassily Kandinsky

🕊️ “Everything starts from a point.”

🧭 “The point is the most concise form but at the same time the most abstract. It is the ultimate expression of silence.”

🎼 “The line is the track made visible by the moving point… it is the first step towards the plane.”

🔥 “Every line possesses its own inner sound.”

🌌 “Geometric forms do not originate in the external world, but in the soul of the artist.”

💡 “Form itself, even if completely abstract and geometrical, has its own inner sound.”

🌀 “Inner necessity is the impulse of the artist to create as a spiritual need.”

🎨 “Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings.”

📐 “The triangle is a form that is spiritually ascending. The square is one of rest, of stability. The circle is the most peaceful shape and movement.”

🔊 “Each form, each color, has a spiritual vibration that resonates with the human soul.”

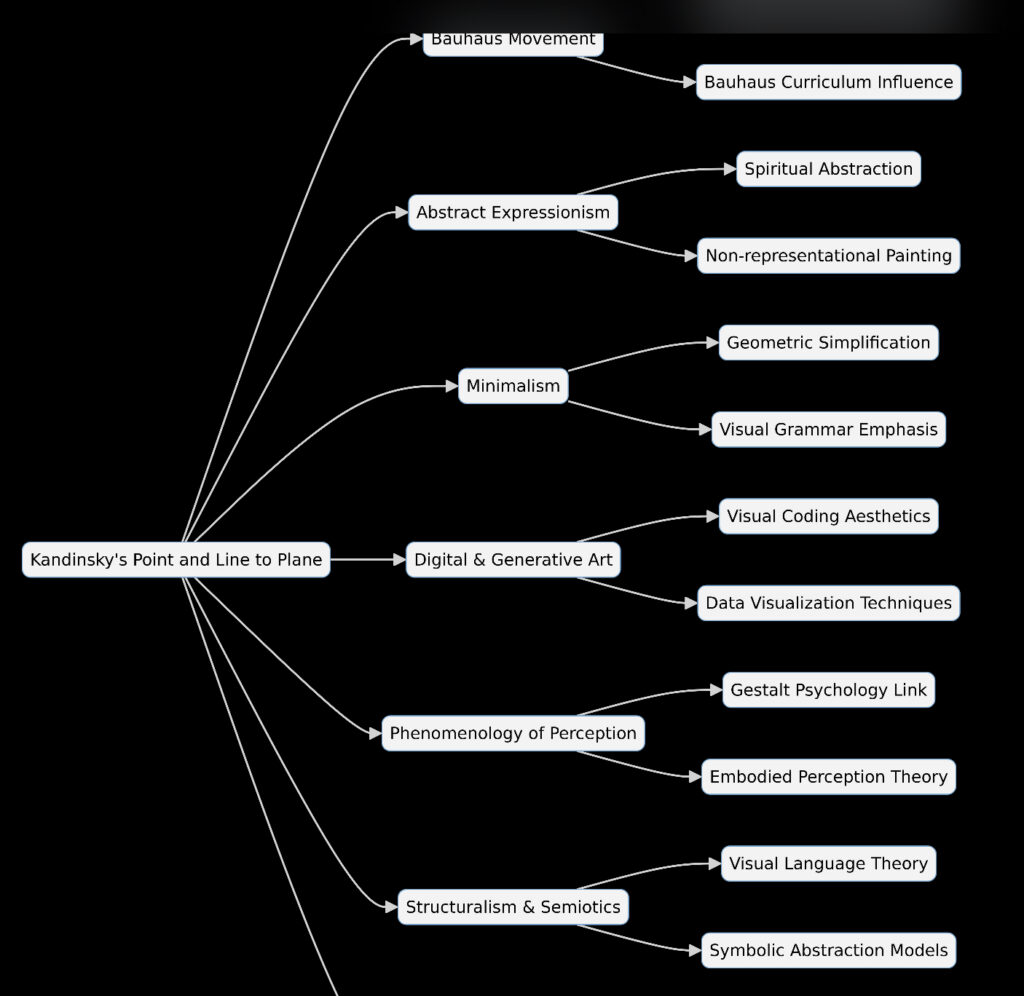

Wassily Kandinsky’s Point and Line to Plane has had a profound influence on both later art history and philosophical aesthetics, especially in the 20th and 21st centuries. Here’s how its impact has manifested:

🖼️ Influence on Art History

🎨 Abstract and Modernist Movements

- Bauhaus School: Kandinsky taught at the Bauhaus (1922–1933), and his formalist theories deeply shaped the curriculum. His breakdown of form into point, line, and plane became a foundational vocabulary for Bauhaus design, architecture, and typography.

- Abstract Expressionism: His ideas about spiritual expression through non-representational forms influenced post-WWII artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman, who prioritized form and emotion over realism.

- Minimalism & Conceptual Art: The notion that basic forms carry intrinsic meaning and can provoke deep emotional/spiritual responses foreshadowed minimalist practices of Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, and Sol LeWitt.

- Digital and Generative Art: Contemporary artists using code and algorithms often echo Kandinsky’s formal rules—points as data nodes, lines as vectors, planes as grids. His work has been cited in media theory and digital visual aesthetics.

📚 Influence on Philosophy and Aesthetics

🧠 Phenomenology and Perception

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Gilles Deleuze explored visual perception and form. Though they didn’t cite Kandinsky directly, his emphasis on the sensory and emotional effects of basic forms is echoed in their writings.

- Gestalt psychology, which emerged at the same time, shares his view that whole configurations (shapes, planes) are perceived before parts.

📏 Structuralism and Semiotics

- The idea of a visual grammar (points = signs, lines = syntax, planes = composition) anticipates semiotic theory—especially in the work of Roland Barthes and Umberto Eco.

- Kandinsky’s concept of form as autonomous meaning resonates with post-structuralist theories that decouple meaning from reference.

💥 Spiritual Aesthetics

- Philosophers of art like Suzanne Langer and Ananda Coomaraswamy later developed spiritual aesthetics that overlapped with Kandinsky’s idea of “inner necessity” and form as expression of the soul.

- His work directly ties to Theosophy and anthroposophical thought (e.g. Rudolf Steiner), influencing esoteric interpretations of art.

📎 Summary of Lasting Impact

- Visual Grammar: Inspired generations to see art not as imitation but as language, with formal “words.”

- Art Pedagogy: Became foundational in design and art school teaching worldwide.

- Digital Art: His theories are echoed in modern software interfaces and visual programming.

- Spiritual Modernism: Reinforced that art could express universal inner truths without representing the visible world.