ChatGPT:

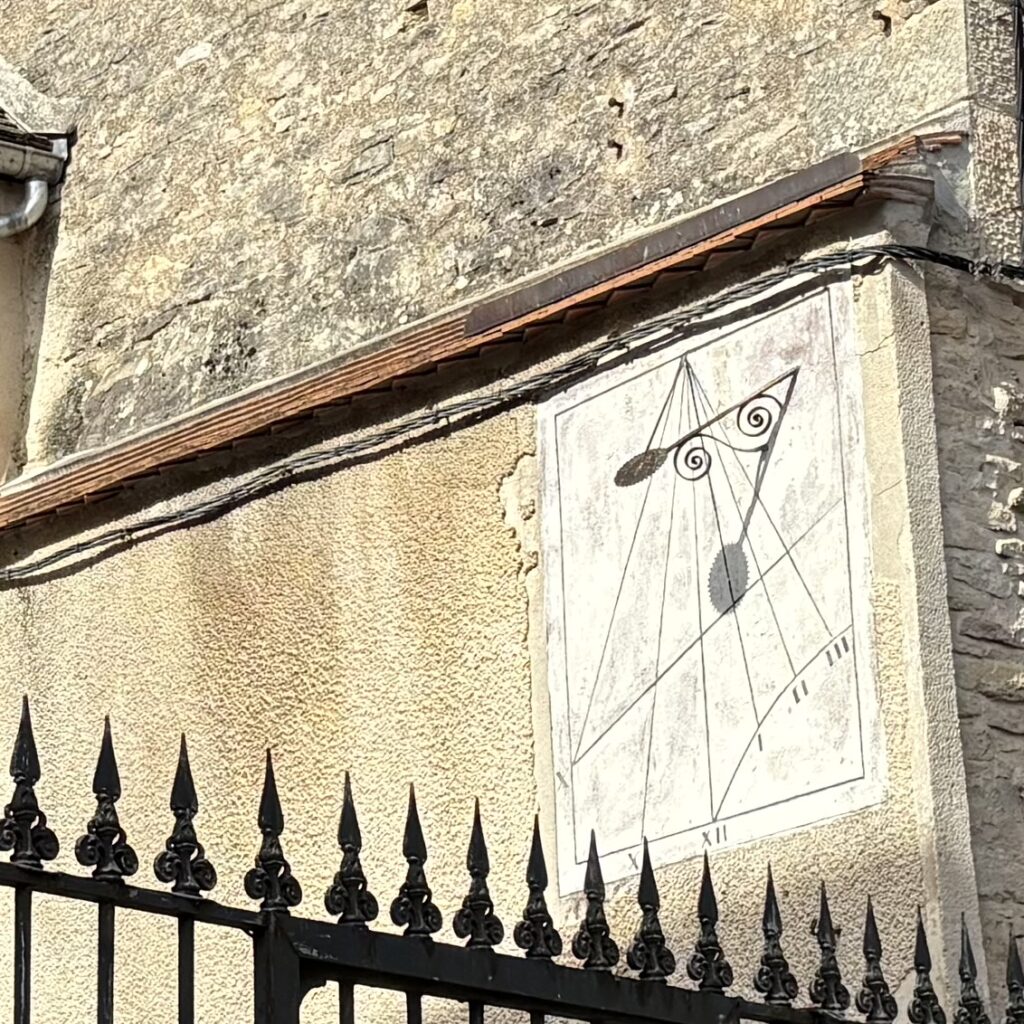

The painting on the wall is a sundial, a traditional timekeeping device that uses the position of the sun to indicate the time of day. Here’s a breakdown of its key features:

1. Gnomon (Shadow-Casting Rod):

• The metal piece protruding from the wall, casting a shadow on the painted dial.

• It has an ornate design, with two spirals near the base, adding an artistic touch.

2. Hour Lines and Numbers:

• The dial is marked with lines that correspond to different hours of the day.

• Roman numerals (such as XII for noon) are visible, indicating time divisions.

3. Shadow Position:

• The sundial is currently in use, as seen from the shadow cast on the dial.

• By observing where the shadow falls, one can estimate the local solar time.

4. Design & Setting:

• The sundial is mounted on an old stone wall, suggesting historical or traditional significance.

• The slightly weathered look adds to its charm, likely blending with the historical character of the building.

Would you like help estimating the time based on the shadow’s position?

“Yes”

To estimate the time from the sundial:

1. Observe the Shadow Position:

• The shadow of the gnomon falls on a line slightly past the X (10) mark and closer to XI (11).

2. Interpretation:

• Since sundials follow solar time, the actual time may be slightly different from modern clock time due to factors like the equation of time and longitude differences within a time zone.

• However, based on the shadow’s position, the local solar time appears to be around 10:30–10:45 AM.

Would you like to adjust for your location’s time zone and daylight saving time to get a more precise estimate?

“It’s in France, in EarlyMarch.”

In early March, France operates on Central European Time (CET, UTC+1) and has not yet switched to daylight saving time (which begins at the end of March).

Adjusting Sundial Time to Clock Time:

1. Sundial shows ~10:30–10:45 AM solar time.

2. France’s standard time is based on the 15°E meridian, while much of France is west of that (closer to ~2°E).

• This means solar noon (when the sun is highest) occurs later than 12:00 CET.

• The approximate correction is +30 to 40 minutes for much of France.

3. Final estimated clock time:

• Adding this correction, the actual time should be around 11:10–11:25 AM CET.

If you want a more precise adjustment, I can refine it based on the exact location in France.

“It’s at Noyers, burgundy.”

Noyers, Burgundy, is located at approximately 3.9°E longitude. To adjust the sundial’s solar time to standard clock time (CET, UTC+1) in early March, we need to apply a longitude correction and the equation of time correction:

- Longitude Correction

• France’s standard time is based on the 15°E meridian, but Noyers is at 3.9°E, meaning it is about 11° west of the standard meridian.

• The sun moves 1° every 4 minutes, so this results in a 44-minute delay in solar time compared to CET. - Equation of Time Correction

• The equation of time accounts for the Earth’s elliptical orbit and axial tilt.

• In early March, the equation of time is around -12 minutes, meaning solar noon happens about 12 minutes earlier than an average solar day. - Final Adjustment

• The sundial shows around 10:30–10:45 AM solar time.

• Adding the longitude correction (+44 min) and the equation of time correction (-12 min):

• 10:30 AM solar time → ~11:02 AM CET

• 10:45 AM solar time → ~11:17 AM CET

Final Estimated Clock Time in Noyers:

Around 11:05–11:20 AM CET.

Would you like me to refine it further based on the exact date?

“March 8, 2025.”

On March 8, 2025, in Noyers, Burgundy, the sundial time of 10:30–10:45 AM solar time corresponds to approximately:

• 11:03 AM CET (for 10:30 AM solar time)

• 11:18 AM CET (for 10:45 AM solar time)

So, the estimated actual clock time in Central European Time (CET) would be between 11:03 and 11:18 AM.

Origin, Type, and Development of the Sundial

Origin of Sundials

Sundials are among the oldest timekeeping devices, dating back to ancient civilizations. The earliest known sundial-like objects appeared in ancient Egypt around 1500 BCE, where shadow clocks (also called obelisks or gnomons) were used to track time by the movement of the sun’s shadow. The Babylonians and Chinese also developed early sundials, refining the use of shadow measurements.

By the 4th century BCE, the Greeks improved sundial designs by applying mathematical principles to calculate time divisions more accurately. The Romans later adopted and popularized sundials throughout their empire, making them common in public places and private homes.

Types of Sundials

Sundials come in various designs, depending on their placement and the position of the gnomon (the shadow-casting component). The main types include:

1. Horizontal Sundial

• The most common type, with a flat surface and an angled gnomon.

• Often found in gardens or courtyards.

2. Vertical Sundial

• Mounted on walls, commonly seen on old European buildings.

• The gnomon is adjusted to match the wall’s orientation.

3. Equatorial Sundial

• The dial plate is parallel to the equator, and the gnomon is aligned with the Earth’s axis.

• Provides consistent hour divisions throughout the year.

4. Analemmatic Sundial

• A unique type where the gnomon’s position is adjusted based on the date.

• Often seen in large public installations, allowing people to stand as the gnomon.

5. Portable Sundials

• Small, handheld devices used historically by travelers and navigators.

• Some were equipped with compasses for better alignment.

Development of Sundials

The sundial evolved over centuries as different cultures refined its accuracy:

• Ancient Greece & Rome (4th century BCE – 5th century CE)

• Greek astronomers like Eratosthenes and Ptolemy contributed to sundial theory.

• Romans spread sundials across Europe and introduced portable versions.

• Islamic Golden Age (8th – 14th century)

• Muslim scientists improved sundial calculations, aligning them with prayer times.

• Al-Battani and Al-Zarqali created highly precise sundials.

• Renaissance Europe (15th – 18th century)

• Advancements in astronomy led to more sophisticated sundials.

• Public sundials became symbols of science and civic pride.

• Modern Era (19th century – Present)

• The invention of mechanical clocks reduced the practical need for sundials.

• Today, sundials are used mainly for educational and decorative purposes, with some digital and hybrid versions integrating GPS for enhanced accuracy.

Conclusion

While mechanical and digital clocks dominate timekeeping today, sundials remain a testament to human ingenuity. They continue to be studied, preserved, and even installed as artistic and scientific tools, bridging ancient knowledge with modern curiosity.