ChatGPT:

Nemrut Dağı (Mount Nemrut) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site in southeastern Turkey, located in the Taurus Mountains near Adıyaman. This archaeological marvel is best known for the monumental tomb-sanctuary of King Antiochus I Theos of Commagene, a small Hellenistic kingdom that flourished in the first century BCE.

Origins and History

• Construction by King Antiochus I: Nemrut Dağı was constructed around 62 BCE by Antiochus I as a grand tomb-sanctuary. Antiochus, the ruler of the Commagene Kingdom, sought to create a monumental site to showcase his divine lineage and celebrate the fusion of Eastern (Persian) and Western (Greek) cultures. His kingdom served as a cultural crossroads between the two worlds.

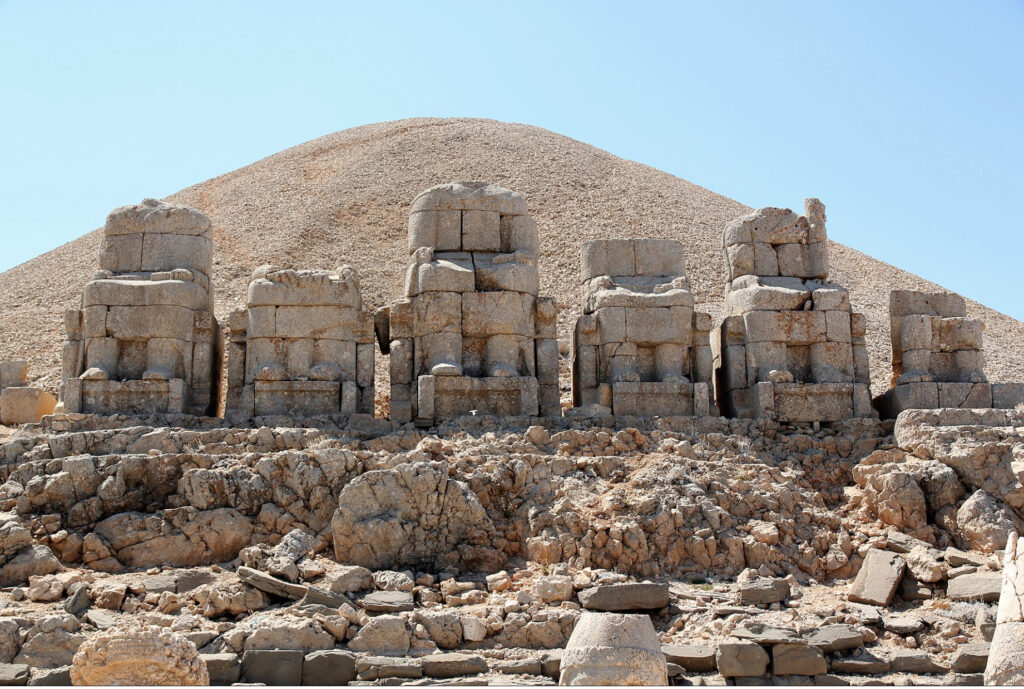

• The Burial Mound: At the summit, a massive 50-meter-high conical tumulus of crushed stones is believed to contain the king’s burial chamber. However, the tomb itself has not yet been excavated, leaving much of its mysteries intact.

• Terraces with Colossal Statues: Surrounding the tumulus are three terraces (east, west, and north), which feature colossal statues (up to 8-9 meters tall) of deities, animals, and the king himself. The deities represent a syncretism of Greek and Persian influences, with figures like Zeus-Oromasdes, Apollo-Mithras, and Heracles-Artagnes.

• Astronomical Alignment: The site is thought to have had an astronomical purpose, with the alignment of some elements possibly linked to religious or calendrical functions.

• Rediscovery: Nemrut Dağı was forgotten for centuries until it was rediscovered in 1881 by a German engineer named Karl Sester. Since then, it has been the subject of extensive archaeological research.

Symbolism

The site reflects Antiochus’s vision of unity between East and West, expressed through the blend of cultural and religious traditions. Antiochus claimed descent from both Persian and Macedonian royalty, and the statues, inscriptions, and site layout emphasize this dual heritage.

Cultural Importance

Nemrut Dağı stands as a testament to the artistic, religious, and political ambitions of the Commagene Kingdom. It is a rare example of a ruler attempting to immortalize their legacy through monumental architecture, blending artistic traditions from both sides of the ancient world.

Today, it is a popular destination for visitors, especially at sunrise and sunset, when the light accentuates the majesty of the statues and the breathtaking views of the surrounding mountains.

Stone Statues on Nemrut Dağı

The most remarkable feature of Nemrut Dağı is the set of colossal statues situated on the eastern and western terraces surrounding the burial mound. These statues, each standing approximately 8-9 meters (26-30 feet) tall when intact, were carved from limestone and represent a combination of Hellenistic and Persian influences.

Identified Statues and Their Symbolism

1. King Antiochus I Theos

• Positioned prominently among the deities, Antiochus portrays himself as a divine ruler, emphasizing his claimed descent from both Persian and Macedonian lineages.

• His statue symbolizes his effort to immortalize his rule and legitimize his authority through divine association.

2. Zeus-Oromasdes

• The chief deity, combining Zeus from Greek mythology and Ahura Mazda from Persian Zoroastrianism.

• Represents divine power and authority.

3. Apollo-Mithras-Helios-Hermes

• A fusion of Greek and Persian deities, symbolizing light, truth, and communication.

4. Heracles-Artagnes-Ares

• A syncretic representation of strength, courage, and martial power.

5. Commagene (Personification)

• A goddess embodying the region of Commagene, symbolizing prosperity and fertility. She is often depicted holding a cornucopia.

6. Eagle and Lion Statues

• Flanking the gods, these animals serve symbolic purposes:

• Eagle: Represents the sky, divine protection, and power.

• Lion: Symbolizes strength and the king’s authority.

• The lion statue also features an astronomical relief, possibly indicating astrological significance tied to Antiochus’s reign.

Construction Techniques

The construction of these massive statues and the tumulus on Nemrut Dağı was an ambitious engineering feat, considering the resources and tools available in the 1st century BCE. Some possible methods include:

Carving and Transportation

• Quarrying: The statues were likely carved from local limestone quarried nearby.

• Carving Techniques: Workers used basic tools like chisels, hammers, and abrasives to shape the stone into detailed figures. The fusion of Greek and Persian styles required skilled artisans familiar with both artistic traditions.

• Transportation: The blocks and statues were likely hauled to the site using sledges and rollers on wooden tracks, relying on teams of animals and human labor.

Assembly

• Segmented Design: The statues were likely carved in sections to ease transportation and assembly. This is evident as the heads of the statues are now separated from their bodies, probably due to earthquake damage or intentional displacement.

• Placement on Terraces: The terraces were carefully leveled and reinforced to hold the weight of the statues. Each statue was placed on stone bases aligned in rows.

Tumulus Construction

• The tumulus, made of crushed limestone, was built using a rubble-fill technique. Stones were piled to create the conical shape, likely to deter looting by making excavation difficult.

Preservation Challenges

• Over time, earthquakes, weathering, and human activities have caused damage to the statues. The heads of the statues have fallen, and some features have eroded, but the site still retains its grandeur.

Significance of the Statues

The colossal size and intricate design of these statues reflect the grandeur of King Antiochus’s vision. They symbolize a unique blend of Greek and Persian art, a testament to the cultural syncretism of the Commagene Kingdom. Despite the passage of millennia, Nemrut Dağı remains a remarkable engineering and artistic achievement.

No, Nemrut Dağı is not explicitly mentioned in any surviving ancient texts or documents from antiquity. The site and its monumental statues were likely constructed with significant local and regional importance during the reign of Antiochus I Theos of Commagene (69–34 BCE), but it did not appear in widely circulated historical accounts of the time.

Why Isn’t It Mentioned in Ancient Documents?

1. Commagene’s Small Size and Isolation:

• The Kingdom of Commagene was a relatively small, client state located in the borderlands between the Roman and Parthian Empires. Although culturally significant, it did not wield the kind of influence that would have attracted the attention of major historians like Herodotus or Strabo.

• The region’s political and cultural impact may have been overshadowed by the larger empires surrounding it.

2. Lack of Widespread Historical Recording:

• Ancient authors often focused on major powers (e.g., Rome, Greece, Persia) and their leaders. Antiochus I’s efforts to immortalize himself through Nemrut Dağı were likely intended more for his local legacy than international recognition.

3. Limited Circulation of Local Histories:

• Antiochus I recorded his intentions and achievements in Greek inscriptions on the site itself. These inscriptions detail his divine claims, lineage, and syncretic religious philosophy. However, such texts were not disseminated widely and were meant primarily for visitors or local subjects.

4. Destruction and Neglect:

• After the decline of the Commagene Kingdom in 72 CE (when it was annexed by Rome), the site likely fell into obscurity. Without active use or maintenance, it became lost to history until its rediscovery in the 19th century.

Evidence from the Site Itself

While ancient historians do not mention Nemrut Dağı, the inscriptions at the site provide detailed insights into its purpose and Antiochus’s intentions:

• Hierothesion Inscriptions:

• Written in Greek, these inscriptions proclaim Antiochus’s divine ancestry and his goal to harmonize Greek and Persian religious traditions.

• They serve as a self-contained historical account by the king for future generations.

Other Indirect Mentions

• The Kingdom of Commagene is briefly mentioned by ancient writers like Strabo (Geographica, Book 16), but there is no specific reference to Nemrut Dağı or the monumental sanctuary.

• Strabo noted that Commagene was a fertile and prosperous land, and he mentioned the dynasty’s Persian and Macedonian lineage, which aligns with the themes of Nemrut Dağı.

In summary, while Nemrut Dağı itself does not appear in ancient documents, the inscriptions on-site provide a rich, self-referential narrative. This makes it a unique archaeological and historical puzzle, relying almost entirely on its physical and epigraphic evidence for interpretation.