ChatGPT:

Uffizi Gallery: Origin, History, and Development

The Uffizi Gallery (Gallerie degli Uffizi) in Florence is one of the world’s most renowned art museums, celebrated for its unparalleled collection of Renaissance masterpieces. Its own story begins in the 16th century under the patronage of the powerful Medici family, evolving over centuries into a premier public institution that continues to expand and adapt.

1. Architectural Origins (Mid-16th Century)

• Commission by Cosimo I de’ Medici (1560)

The project for the Uffizi (“offices”) was conceived by Cosimo I de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, who sought to centralize the administrative and judicial offices of Florence.

• Design by Giorgio Vasari

Giorgio Vasari, a painter, architect, and writer famed for his “Lives of the Artists,” was tasked with creating a unified and functional building along the Arno River—near the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of political power. Construction began in 1560.

• Structure and Layout

• The design features a narrow courtyard flanked by two long wings, leading toward the river and visually connecting to the Palazzo Vecchio.

• Vasari also built an elevated passage, the Vasari Corridor (1565), which allowed the Medici to move privately between the Uffizi and the Pitti Palace across the Arno.

2. Early Use and Formation of a Gallery (Late 16th–17th Century)

• Administrative Offices

True to its name, the Uffizi initially served as the central offices for Florence’s magistrates, guilds, and state administration.

• Art Collection Begins

Cosimo I’s son, Francesco I de’ Medici, had a profound interest in art and science. In the late 16th century, he repurposed part of the upper floor to display the Medici’s growing collection of paintings, sculptures, scientific instruments, and curiosities.

• Tribuna of the Uffizi

Designed for Francesco I in the late 16th century by architect Bernardo Buontalenti, the Tribuna was a dedicated octagonal room showcasing the family’s most precious and rare works—a precursor to the modern “museum room.”

3. Transition to a Public Museum (18th–19th Century)

• Medici Legacy and the House of Habsburg-Lorraine

The Medici line ended with Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici in 1743. In her “Patto di Famiglia” (Family Pact), she bequeathed the Medici art collections to the Tuscan state on the condition that they remain in Florence for public enjoyment.

• Official Opening

By the mid-18th century, under the Habsburg-Lorraine rulers (who succeeded the Medici in Tuscany), the Uffizi’s collection became increasingly accessible. In 1769, the gallery was more formally opened to visitors, though initially admission was limited and typically by request or invitation.

• 19th-Century Developments

During the 1800s, as public museums gained popularity across Europe, the Uffizi underwent reorganizations and expansions. Efforts were made to display the artworks more systematically, reflecting Enlightenment and then Romantic-era ideas about art and cultural heritage.

4. Modernization and Growth (20th Century)

• Early 20th Century

The Uffizi established itself as one of Europe’s leading art museums, undergoing restoration and cataloging efforts. Scholar-curators began serious research on the provenance and dating of the artworks.

• World War II and Recovery

The gallery’s proximity to the Arno River and central location put it at risk during wartime. Many artworks were evacuated for safety; though Florence was bombed, the Uffizi’s core structure survived.

• Post-War to Late 20th Century

• The Uffizi faced challenges including overcrowding and the need for modern lighting, security, and climate control.

• In 1993, a car bomb planted by the Mafia damaged parts of the Uffizi and destroyed several artworks, prompting renewed restoration and security measures.

5. Recent Renovations and the “Nuovi Uffizi” Project (21st Century)

• Nuovi Uffizi (New Uffizi) Renovation

A major multi-phase expansion and reorganization project was launched in the early 2000s to address issues of space, visitor flow, and conservation.

• Additional Rooms: Many more exhibition rooms were opened, allowing previously stored or rarely displayed artworks to be showcased.

• Reworked Layout: Sections were grouped by period or artist for a clearer narrative of art history, particularly from the Gothic to High Renaissance eras.

• Modern Amenities: Improved ticketing, expanded cloakrooms, cafes, and bookstore facilities for a more visitor-friendly experience.

• Global Recognition

The Uffizi remains at the forefront of art scholarship and tourism. Millions of visitors each year experience masterpieces by Giotto, Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian, Caravaggio, and beyond.

6. Cultural Significance

• Cradle of Renaissance Art

The Uffizi collection documents the trajectory of Western art from medieval iconography through the apex of the Renaissance, showcasing Tuscan contributions to painting and sculpture.

• Scholarly Hub

The gallery’s archives and academic collaborations make it a center for conservation research, art historical study, and cultural dissemination.

• Tourist Destination

As one of the most visited museums in Italy, the Uffizi shapes Florence’s identity and economy, drawing scholars, students, and art enthusiasts from around the globe.

Conclusion

From its origins as a seat of Florentine administration under Cosimo I de’ Medici to its role as one of the world’s premier art museums, the Uffizi Gallery reflects Florence’s extraordinary cultural legacy. Over centuries, it has evolved—from the Medici’s private collection space to a pioneering public institution—while remaining a cornerstone of Renaissance art and a living testament to the city’s enduring commitment to beauty, learning, and heritage.

Architectural Characteristics and Specific Features of the Uffizi

The Uffizi Gallery originally intended as a centralized administrative complex (“uffizi” meaning “offices”), the building embodies late Renaissance or Mannerist architectural principles. While it primarily served a civic function, its layout and aesthetics would later help transform it into one of the world’s most famous art museums. Below are the key architectural characteristics and notable features that define the Uffizi’s design:

1. Overall Layout

1. U-Shaped Plan

• The complex consists of two long, parallel wings connected at one end by a short cross-section. This U-shaped layout encloses a narrow courtyard that visually guides the viewer’s gaze toward the Arno River.

• The courtyard is open at the river-facing end, creating a theatrical perspective that culminates in a view of the Ponte Vecchio and the distant horizon.

2. Connection to Palazzo Vecchio

• Because the Uffizi adjoins the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence’s historic seat of government, the building’s positioning reinforces its role as an administrative center.

• The courtyard’s architecture also aligns with the massing of Palazzo Vecchio, underscoring the unity of civic power in Renaissance Florence.

2. Facade and Exterior Elements

1. Mannerist Restraint

• Compared to the ornate decoration of earlier Renaissance or Baroque structures, the Uffizi’s exterior is marked by a controlled, almost severe elegance—a characteristic of Mannerist architecture.

• The facade uses repetition of arches and pilasters, achieving symmetry and rhythm without excessive ornamentation.

2. Loggias and Arcades

• Tall arcades on the ground floor create a covered walkway around the courtyard, providing shelter and open sightlines.

• Rounded arches rest on columns or pilasters with Ionic or Doric capitals, giving a classical refinement to the design.

3. Rustication and Smooth Ashlar

• The lower stories feature partial rustication on the stone surfaces around doors and windows, giving the base a solid, fortress-like look.

• Moving upward, the stonework transitions to smooth ashlar, emphasizing height and a sense of lightness.

4. Vertical Emphasis

• The tall, narrow proportions of the courtyard and the windows, combined with projecting cornices, draw the eye upward.

• This sense of verticality is balanced by the horizontal lines of string courses and cornices, creating visual harmony.

3. Interior Spaces

1. Upper Gallery

• The most famous section is the long corridor on the top floor—once an administrative hallway—now housing extensive art collections.

• The corridor’s large, evenly spaced windows allow natural light to illuminate the artworks while offering views of the Arno River and the city.

2. Tribuna

• Designed by Bernardo Buontalenti in the late 16th century for Francesco I de’ Medici, the Tribuna is a distinctive octagonal room originally intended to showcase the Medici’s most prized art and curiosities.

• Known for its red velvet walls, inlaid marble floor, and domed ceiling adorned with mother-of-pearl, the Tribuna exemplifies the luxurious side of late Renaissance interior design.

3. Vasari Corridor

• Built in 1565, the Vasari Corridor is an elevated passage that connects the Uffizi to the Pitti Palace across the Arno.

• This corridor allowed the Medici to move securely between their administrative offices and private residence. Today, it serves as part of the museum complex, displaying a unique collection of portraits.

4. Decorative and Functional Details

1. Repetitive Window Bays

• Each floor features a pattern of repeated window bays framed by pilasters or columns, providing both functional ventilation and balanced aesthetics.

• Windows on the top floor are often arch-topped, enhancing the building’s Mannerist elegance.

2. Monumental Staircases

• Originally built to accommodate public offices, the interior staircases were designed to handle high foot traffic. In modern times, these staircases help manage the significant number of museum visitors.

3. Use of Natural Light

• Many of the upper-level rooms and corridors rely on large windows for lighting, a design choice that was especially forward-thinking for a 16th-century complex.

• The interplay of light and shadow across the arcades and within the corridors underscores the architectural drama typical of Mannerist sensibilities.

5. Legacy and Influence

• Prototype for Administrative Complexes

• The Uffizi’s orderly layout, with clearly separated wings and a centralized courtyard, influenced subsequent civic building designs in Europe.

• Adaptive Reuse

• Its shift from government offices to one of the earliest modern art galleries demonstrates how Renaissance architecture could be repurposed for cultural needs.

• Tourist and Cultural Hub

• The courtyard’s open design encourages public circulation, establishing the Uffizi as a social and cultural gathering place at the heart of Florence.

Conclusion

The Uffizi exemplifies late Renaissance (Mannerist) architecture through its harmonious proportions, restrained ornamentation, and functional layout. Vasari’s vision, later complemented by contributions from Buontalenti and others, resulted in a building that not only served administrative needs but also provided an ideal setting for displaying art. Today, those same architectural characteristics—its narrow, elegant courtyard, sequential galleries, and adaptation to modern museum standards—continue to captivate visitors as they explore one of the greatest art collections in the world.

Below is a curated selection of major artworks in the Uffizi Gallery, grouped broadly by art-historical periods. While the Uffizi is especially famous for its Renaissance collection, it also holds significant examples from the late medieval (Gothic) era through the Baroque. Note that dates of creation and exact classification may vary slightly among art historians, but this list provides a helpful chronological framework.

1. Late Medieval / Proto-Renaissance (13th & 14th Centuries)

1. Cimabue, Maestà (c. 1280–1290)

• One of the earliest large-scale panel paintings in Florence, showcasing the transitional style from Byzantine to more naturalistic representation.

2. Duccio di Buoninsegna, Rucellai Madonna (c. 1285)

• Commissioned for the church of Santa Maria Novella; notable for its elegant linearity and use of gold background.

3. Giotto di Bondone, Ognissanti Madonna (c. 1310)

• A groundbreaking work demonstrating Giotto’s move toward greater three-dimensionality and human emotion in religious art.

2. Early Renaissance (15th Century)

1. Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi (1423)

• A masterpiece of International Gothic style transitioning into Renaissance naturalism, celebrated for its lavish detail and use of gold.

2. Fra Angelico, Annunciation (various versions; c. 1420s–1430s)

• Fra Angelico’s serene figures and luminous colors exemplify the spiritual and lyrical quality of early Renaissance painting.

3. Paolo Uccello, Battle of San Romano (c. 1435–1440)

• Famous for its early experimentation with perspective and foreshortening in a dynamic battle scene.

4. Piero della Francesca, Diptych of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza (c. 1472)

• A landmark in portraiture and perspective, depicting the Duke and Duchess of Urbino against idealized landscapes.

5. Pollaiuolo, Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1470s)

• Demonstrates the fascination with detailed realism and individualized features in 15th-century Florentine portraiture.

3. High Renaissance (Late 15th to Early 16th Century)

1. Sandro Botticelli, Primavera (c. 1477–1482)

• An allegorical celebration of spring with mythological figures, renowned for its poetic beauty and graceful linear style.

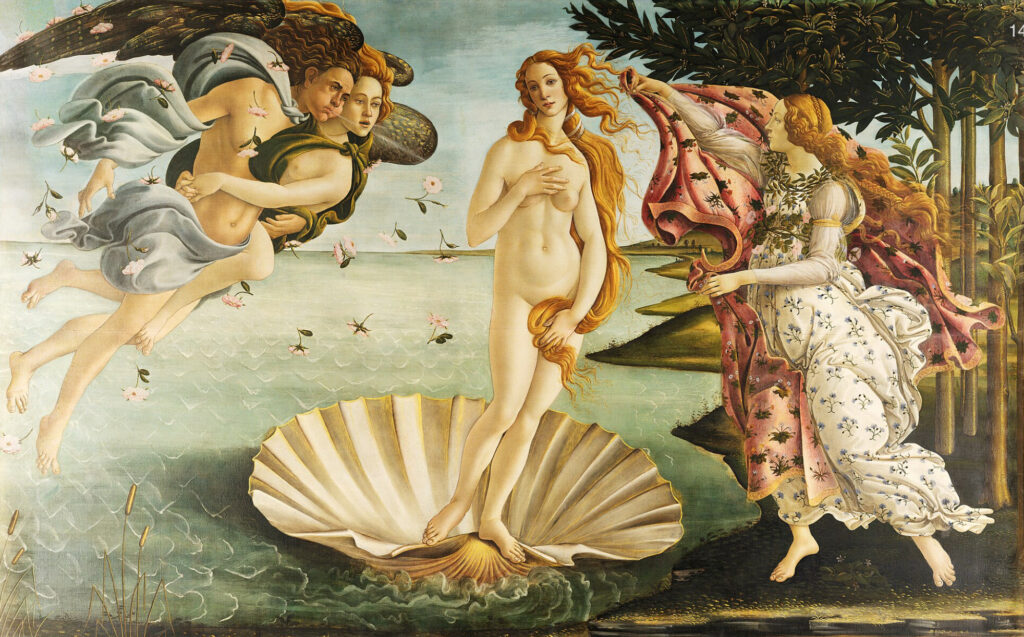

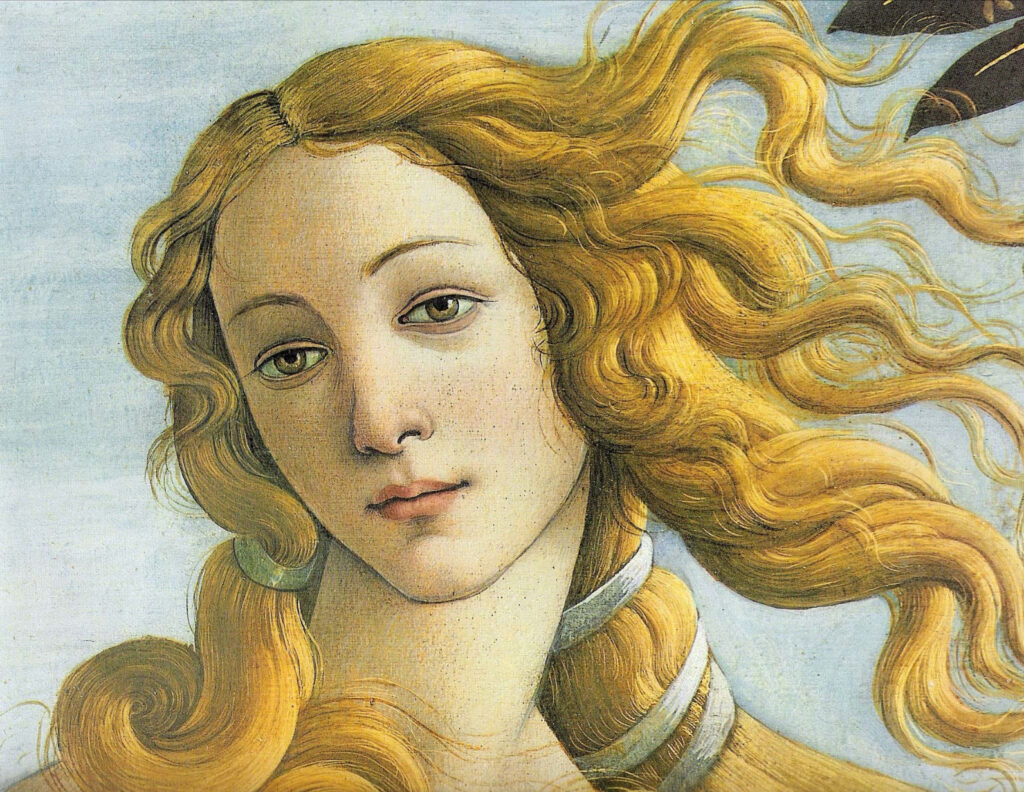

2. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–1486)

• One of the Uffizi’s most iconic works, featuring the goddess Venus emerging from the sea on a shell, symbolizing love and beauty.

3. Leonardo da Vinci, Annunciation (c. 1472–1475)

• A youthful Leonardo masterpiece displaying his early mastery of atmospheric perspective and delicate sfumato.

4. Michelangelo Buonarroti, Doni Tondo (Holy Family) (c. 1504–1507)

• Michelangelo’s only finished panel painting; noted for its sculptural figures and vibrant color transitions, bridging High Renaissance and Mannerism.

5. Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), Madonna del Cardellino (Madonna of the Goldfinch) (c. 1506)

• Exemplifies Raphael’s harmonious compositions, tender depiction of the Virgin with Child, and a balanced use of perspective.

4. Mannerism (Mid-16th Century)

1. Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleonora di Toledo with her son Giovanni (c. 1544–1545)

• A courtly portrait emphasizing elegant fashion and refined, idealized features, typical of Mannerist portraiture in Medici Florence.

2. Giorgio Vasari, Allegory of the Immaculate Conception (c. 1541)

• By the architect/painter of the Uffizi itself, showcasing the elongated forms and refined style of Mannerism.

3. Parmigianino, Madonna dal Collo Lungo (Madonna with the Long Neck) (Note: This painting is traditionally associated with the Uffizi but actually resides in the Palazzo Pitti complex; however, Parmigianino’s Mannerist style is represented in the Uffizi by other works, including self-portraits.)

(If you specifically look for Parmigianino’s Mannerist style in the Uffizi, you may find self-portraits or smaller works of his or his circle.)

5. Late Renaissance to Baroque (Late 16th to 17th Century)

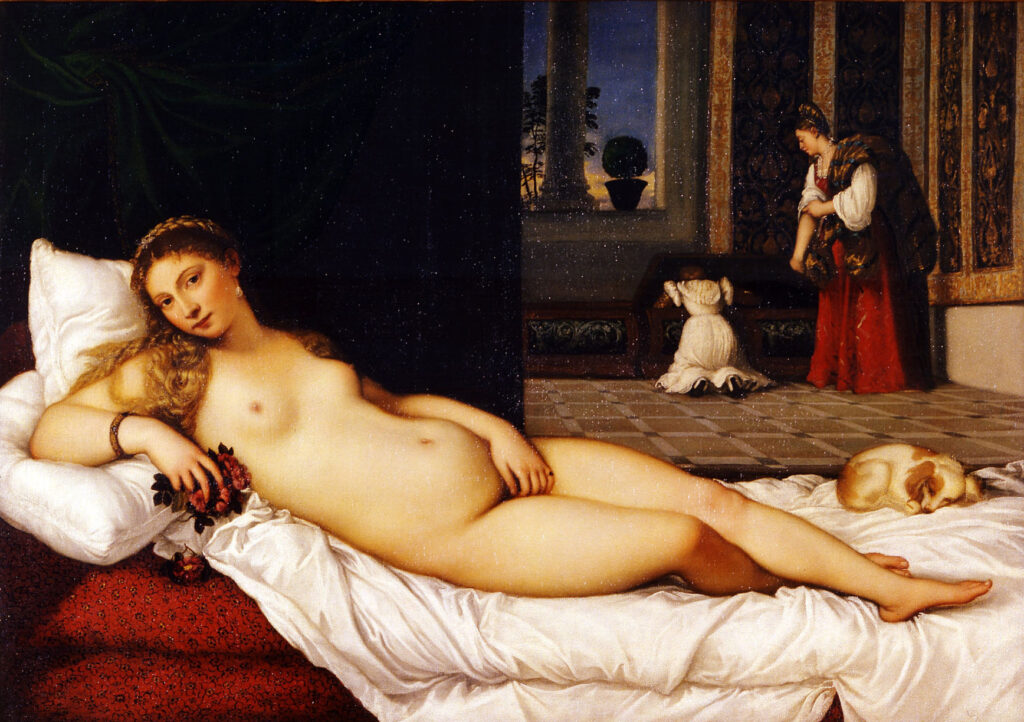

1. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Venus of Urbino (c. 1538)

• Sometimes considered High Renaissance yet foreshadowing Baroque sensuality, this iconic nude painting influenced later Western art.

2. Veronese (Paolo Caliari), Portrait of a Gentleman in a Fur (c. 1570s)

• Demonstrates the opulent Venetian approach to color and texture during the late Renaissance.

3. Caravaggio, Medusa (c. 1597)

• A striking shield painting, capturing the horrified expression of Medusa at the moment of her decapitation; dramatic lighting (chiaroscuro) exemplifies Caravaggio’s style.

4. Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Holofernes (c. early 17th century)

• Artemisia’s intense Baroque interpretation of this biblical story highlights her mastery of light, shadow, and emotional narrative (several versions exist; the Uffizi’s piece is one of her best-known works).

Additional Notes

• Sculpture Collection: Although primarily famous for paintings, the Uffizi also houses significant antique sculptures, Roman copies of Greek originals, and Renaissance/Baroque statues.

• Continuous Expansion: The museum frequently reorganizes its rooms and exhibits, so some works may move or occasionally be on loan; always consult the official Uffizi website or updated guidebooks for current displays.

These highlights cover the major phases of Italian art represented in the Uffizi, guiding visitors from the flowering of the early Florentine Renaissance to the dynamic light-and-shadow drama of Baroque painting.