ChatGPT:

Why You Feel Scared, in Love, and Occasionally Like Screaming into a Pillow: A User’s Guide to the Emotional Brain

Let’s start with a confession: your emotions are not nearly as mysterious or romantic as you think. They are, in large part, your body’s housekeeping notifications — automatic updates about what’s going on inside you, wrapped in melodrama. Fear, love, rage, joy — they’re all variations of the same thing: your brain trying to interpret the chaos of your physiology and pretending it meant to do that.

The Original Alarm System: Fear and the Amygdala

Fear is the Beyoncé of emotions — ancient, powerful, and a bit of a control freak. Deep in your brain’s temporal lobes sit two almond-shaped clusters called the amygdalae. They’re your built-in threat detectors, honed over millions of years of keeping our ancestors from being eaten or electrocuted by novelty.

When something potentially dangerous appears — a snake, a loud bang, or a “We need to talk” text — the signal rushes to the amygdala before the rational parts of your brain (the prefrontal cortex) even clock in for the day. This “low road” pathway allows you to react before you think. You jump, scream, or spill your coffee long before you consciously realize it’s just the cat. The amygdala then alerts the hypothalamus, which triggers the fight-or-flight system: your heart pounds, pupils widen, and blood shunts to your muscles so you can sprint, punch, or — most commonly — stand there doing neither while regretting your life choices.

The irony is that this lightning-fast reflex once saved us from predators. Now it’s mostly deployed against PowerPoint presentations, exams, and phone calls from unknown numbers. Evolution, it seems, didn’t foresee voicemail.

Why We Fear Non-Lethal Things

From a psychological perspective, modern fear is a case of evolutionary misapplication. Your threat system can’t tell the difference between a tiger and a judgmental audience. Both feel like potential extinction events to your social brain. For ancient humans, being rejected by the tribe meant death by isolation. So when you face public speaking or a Tinder date, your amygdala still assumes the stakes are survival. Congratulations — your biology is stuck in the Pleistocene.

Moreover, your brain has a talent for conditioning. If something stressful happens (say, bombing a math test), your nervous system learns to associate that context with threat. Years later, even the smell of a classroom might give you heart palpitations. Fear is efficient that way — it learns fast and forgets slowly.

The Physiology Behind Emotion: When the Body Bosses the Brain

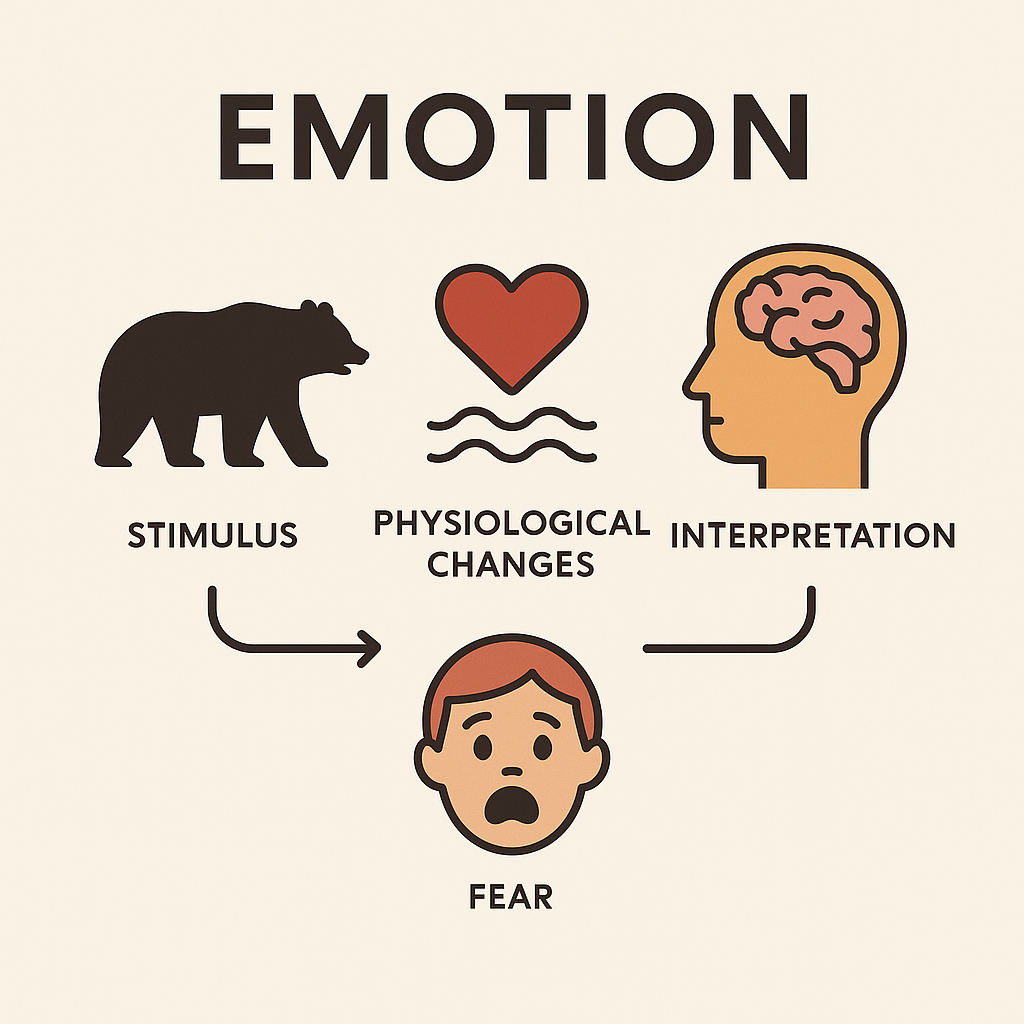

Here’s where things get philosophical — and oddly sweaty. In the 1880s, psychologist William James suggested a radical idea: emotions aren’t the cause of bodily reactions; they’re the result. He argued that we don’t tremble because we’re afraid — we feel afraid because we notice ourselves trembling. The body moves first, and the brain retrofits a feeling to match.

This idea became known as the James–Lange theory of emotion, and while his colleagues politely wondered if he’d inhaled too much Victorian ether, he turned out to be surprisingly right. Modern neuroscience confirms that interoception — the brain’s monitoring of bodily states — is crucial to emotion. When your heart races, palms sweat, and gut clenches, your brain reads these internal signals and asks, “What story fits this data?” If you’re watching a horror film, the answer is “fear.” If you’re on a date, it might be “love.” Context decides the label.

Predictive Brains: Emotions as Best Guesses

Today, scientists describe emotion using predictive modeling. The brain isn’t just reacting to bodily sensations — it’s predicting them. Your nervous system constantly forecasts what’s about to happen in your body (heart rate, breathing, energy level) and adjusts to minimize surprises, a process called allostasis.

So when you meet someone attractive, your brain predicts that your heart rate will rise, your palms will sweat, and you’ll act like a malfunctioning Roomba. Those predictions trigger the physical changes before the event is fully interpreted. When the sensations arrive, the brain checks: “Does this match my love template?” If yes, it declares, “I’m falling in love.” The same bodily pattern in a dark alley might instead be labeled “terror.”

In short: your brain is a storytelling machine guessing why your body feels weird. Emotions are those guesses, rendered in high definition.

Love: The More Enjoyable Panic Attack

Let’s test this theory with everyone’s favorite form of emotional insanity: falling in love.

When you see someone who catches your attention, your amygdala and reward circuits (especially the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens) go into overdrive. Dopamine surges, focusing your attention like a laser pointer. Adrenaline and norepinephrine create that racing-heart, flushed-face, “I suddenly forgot how to form sentences” feeling. Your brain perceives these changes and, considering the context (“They smiled at me!”), labels them as attraction or love.

Then the oxytocin system kicks in, cementing trust and attachment. Over time, the beloved becomes part of your internal model of safety — literally woven into your brain’s predictions for comfort and regulation. That’s why losing them later hurts like an amputation: the brain keeps predicting their presence and can’t reconcile the error. Heartbreak, biologically speaking, is just prediction failure with a Spotify playlist.

From James to the Present: How Our Theories Evolved

Psychology didn’t stop with James. In the 1960s, Schachter and Singer proposed the Two-Factor Theory: first comes physiological arousal, then the brain labels it based on context. A pounding heart at a concert becomes “excitement,” but the same heartbeat during turbulence becomes “panic.”

Modern neuroscience, particularly the work of Antonio Damasio and Lisa Feldman Barrett, reframes emotion as constructed experience. The body provides raw signals; the brain interprets them through memory, language, and culture. Emotion isn’t something that happens to you — it’s something your brain builds to explain what’s happening inside you.

So What Are We Really Feeling?

In the end, fear, love, anger, sadness — they’re all interpretations of shifting physiological landscapes. Your amygdala sets off alarms, your cortex writes the captions, and your body supplies the special effects.

This system is brilliant but not perfect. Sometimes it misfires — panic attacks, phobias, irrational jealousies — all just overactive predictions. Other times, it delivers masterpieces of human experience: art, connection, devotion, courage.

So the next time your heart races and your palms sweat, remember: your body is just doing data entry. Your brain is the overcaffeinated intern turning it into a story. Whether you call that story “fear,” “love,” or “Tuesday” depends entirely on the context — and, of course, on how convincing you find your own plot twists.