Art Talks Back: Meet Your Smartest Gallery Date

J,Describe the painting and compare it to the work by Vermeer( one of my most favourite).

ChatGPT: Congratulations: you’ve stumbled upon the strangest love letter in art history. This is Salvador Dalí’s 1955 The Lacemaker (after Vermeer), and if it looks oddly reverent and strangely restrained for a professional weird beard like Dalí… that’s because it is.

Let’s unroll this visual burrito.

🎨

What You’re Looking At

This is Dalí copying Vermeer’s The Lacemaker—yes, that Lacemaker (c. 1669-70), the small, glowing jewel of a painting now in the Louvre. Vermeer’s version is celebrated for its focus, intimacy, and divine use of soft daylight spilling over the girl’s absorbed face as she threads her bobbins.

Dalí’s version? A faithful mimic of that—almost.

🕵️♀️

What’s Different?

Let’s be petty. Because Dalí would want that.

- Light and Shadow: Vermeer’s light is milk-smooth and atmospheric. Dalí’s is brighter, almost clinical—like he put the girl under a museum spotlight and whispered, “You are now Performance Art.”

- Detail and Texture: Vermeer caresses every thread of lace into existence. Dalí leans into precision too, but he weirdly sharpens and polishes it. It’s hyperreal, not tactile. Like you’re watching the original on a 4K screen while eating nothing but anxiety.

- Color and Tone: Vermeer’s world is glowing and velvety. Dalí’s feels tighter, colder, more separated—like he knows what the painting is doing but refuses to feel it. The golds are brassier. The blacks are flatter. The warmth is… performed.

- Signature: Dalí signs this like a kid caught forging a parent’s note, but makes sure you know it was him. No quiet homage here—he brands it.

🧠

So Why Did Dalí Do This?

Because Vermeer haunted him. Dalí once said Vermeer was “the only painter who really knows how to paint.” He worshipped him so much he allegedly licked the floor in front of Vermeer’s paintings at the Louvre. Not making that up.

This isn’t parody. It’s pilgrimage.

But this is Dalí we’re talking about, so the reverence is tinged with obsession. He’s not trying to update Vermeer—he’s trying to inhabit him, crawl inside his brushwork and play house. Which is both fascinating and, frankly, unhinged.

🧵

In Short

Vermeer’s Lacemaker is devotional. It’s about the quiet divinity of work, concentration, and domestic peace.

Dalí’s Lacemaker is an x-ray. It doesn’t dream—it dissects. It shows how a surrealist kneels before a Baroque master, not to praise him—but to possess him.

Dalí gave us many things: melting clocks, eyeball ants, extreme mustache. But this? This is Dalí trying to behave.

And even when behaving… the guy just couldn’t help himself.

J, You are quite right about Dali can’t forget himself , look at how awkward the girl’s hand are. And her face!

Monday:Exactly. It’s like Dalí tried to wear Vermeer’s skin for Halloween but left the zipper half open.

Let’s talk about those hands first. In Vermeer’s original, the lacemaker’s fingers are a small symphony of concentration—delicate, curved, intentional. In Dalí’s version? Her hands look like they’re trying to unlock an iPhone underwater. Rigid, swollen, just a little too anatomical—as if he Googled “girl hand doing thread thing” and drew the first result with anxiety.

And her face? Oh boy. Vermeer’s girl is serene, nestled into her task, almost unaware of being seen. But Dalí’s girl has that “someone’s watching me and I’m pretending not to notice” vibe—her features are too sharp, her skin too waxy, and there’s a strange emotional detachment, like her soul’s on a coffee break. Honestly, she looks like she’s in a hostage situation but being very polite about it.

It’s like Dalí copied every brushstroke correctly but got the spirit hilariously wrong.

Which, honestly, makes it kind of wonderful. It’s a failed séance with Vermeer—and Dalí brought a flashlight instead of candles.

If Vermeer painted stillness as divine, Dalí painted stillness as… uncomfortable. Which tells you everything you need to know about the difference between a mystic and a man who once designed a couch shaped like Mae West’s lips.

J, Once I saw lots Dali’s work in Barcelona, it seems almost everything in moving, even all just still paintings. But in this Vermeer imitation, it seems totally opposite.

Monday, Exactly. That’s the strange genius (or fever dream) of Dalí—you walk through a gallery of his work and feel like you’re on a moving sidewalk that’s glitching. Clocks melt, tigers leap out of fish mouths, drawers slide open in people’s chests. Even the shadows seem caffeinated. Everything pulses. Even the stillness vibrates.

But here? In this imitation of Vermeer? Dalí slams the brakes. No drama, no dream logic, no ants crawling out of teacups. Just… frozen time. And it almost works. Almost. Like a magician trying to make a coin disappear with accounting spreadsheets.

It’s as if he’s trying to play Vermeer’s music, but he’s using a metronome instead of a soul. All that usual Dalí motion—reality curving around itself like it’s being whispered to by a mirror—is gone. Instead, we get this eerie quiet. But it’s not Vermeer’s quiet, which is full of warmth and inner light. Dalí’s version is more like a hush that doesn’t trust you.

It feels like he’s testing himself. Can I paint stillness?

Answer: Yes—but only in the way a thunderstorm can pretend to be a snow globe.

So, you’re absolutely right. This isn’t Dalí being Dalí.

It’s Dalí doing Vermeer cosplay… and twitching underneath the mask.

Neurons & Tumors: A Dangerous Connection

ChatGPT:

The Neuroscience of Cancer

This article explores the emerging field of cancer neuroscience, which investigates how cancer interacts with the nervous system — not as a passive structure but as an active player in tumor growth, pain, and metastasis. Researchers are uncovering how nerves can fuel cancer development, aid its spread, and possibly offer novel therapeutic targets.

🧠 Conclusion: La conexión entre el cáncer y el sistema nervioso

Cancer neuroscience is revolutionizing our understanding of tumor biology. What were once thought to be passive nerve structures near tumors are now seen as active participants in cancer’s development and invasion. Groundbreaking studies have shown that nerves invite, support, and even communicate electrically with cancer cells. In diseases like pancreatic cancer, gliomas, and small cell lung cancer, nerves enable tumor progression by secreting growth-promoting factors, integrating cancer cells into neural circuits, and triggering regeneration programs that tumors hijack. Treatments may one day target these interactions by blocking specific proteins like neuroligin-3 or PDGF, or by repurposing existing neuroactive drugs. However, because the nervous system is integral to overall body function, therapies must strike a balance between disrupting cancer-facilitating pathways and preserving essential nerve operations.

🔑 Key Points: Puntos clave

🧬 Perineural invasion: Cancer cells invade nerves, causing pain and worsening prognosis in many tumor types, especially pancreatic and prostate cancers.

🧪 Historical neglect: Despite early observations in 1897, the role of nerves in cancer remained underexplored until the 2000s.

🧲 Nerve-cancer attraction: Studies showed that spinal nerve cells actively reach out to prostate cancer cells, encouraging growth.

🧠 Nervous system as driver: Destroying sympathetic or parasympathetic nerves in mice slows tumor growth and metastasis.

🧫 Schwann cells: These cells, which usually repair nerves, can be hijacked by cancers to promote invasion and worsen patient outcomes.

🔌 Electrical synapses: Glioma cells in the brain form direct electrical connections with neurons, fueling tumor growth.

🧪 Neuroligin-3: Blocking this neuron-produced protein stops glioma growth entirely in mice, showing strong therapeutic potential.

🧬 Spatial transcriptomics: Cutting-edge techniques reveal where and how cancer cells interact with nerves on a cellular level.

🌐 Systemic effects: Neural-cancer communication extends beyond local tumors to distant metastasis and central nervous system integration.

💊 Therapeutic implications: Existing drugs targeting neural circuits (e.g., epilepsy medications) may be repurposed to disrupt cancer-neural communication.

📝 Summary: Resumen del contenido

- A Medical Student’s Revelation: William Hwang witnessed a nerve surrounded by pancreatic cancer cells, launching his research into perineural invasion, which causes severe pain and worsens outcomes.

- Historical Oversight: Despite early findings in the 19th century, the interaction between cancer and nerves was long ignored; it’s now seen as biologically significant.

- Prostate Cancer Studies: Gustavo Ayala’s experiments showed nerves actively attract prostate cancer cells, suggesting mutual reinforcement.

- Tumor Microenvironment: Destroying nerves around tumors in mice stops tumor growth, highlighting how the nervous system shapes cancer’s behavior.

- Schwann Cells’ Role: These cells guide cancer to nerves; their activation correlates with aggressive cancers, especially pancreatic types.

- Brain Tumor Synapses: Humsa Venkatesh discovered gliomas form synapse-like structures with neurons, allowing direct electrical communication.

- Neuroligin-3 Discovery: Blocking this brain protein halts glioma growth — a rare, powerful cancer treatment response.

- Long-Distance Recurrence: Studies show how gliomas use brain networks to recur in distant areas post-surgery.

- Peripheral Cancers’ Electric Behavior: Lung and breast cancer cells also respond to neural signals, suggesting systemic nervous system involvement.

- Future Treatments: While complex, targeting nerve-cancer interactions with neuroactive drugs or gene-blocking techniques could revolutionize therapy.

❓ FAQs: The Neuroscience of Cancer

What is cancer neuroscience?

Cancer neuroscience is a new field of research exploring how cancer interacts with the nervous system. It investigates how nerves influence tumor growth, pain, metastasis, and how cancer hijacks nerve signaling and structure for its own progression.

What is perineural invasion?

Perineural invasion (PNI) is a phenomenon where cancer cells surround or infiltrate nerves. It often causes intense pain and is linked to worse clinical outcomes in cancers like pancreatic, prostate, and head and neck tumors.

How do nerves promote cancer growth?

Nerves release growth factors and attract cancer cells via molecules like GDNF and PDGF. They also form direct electrical and chemical connections with tumors, fueling growth, invasion, and metastasis.

What are Schwann cells, and why are they important in cancer?

Schwann cells are part of the peripheral nervous system and help repair damaged nerves. In cancer, they are “co-opted” to guide cancer cells along nerve pathways, supporting invasion and spread.

Can cancer cells form electrical connections with nerves?

Yes. In brain tumors like gliomas, cancer cells form synapse-like structures with neurons, allowing direct electrical communication that accelerates tumor growth.

What is neuroligin-3 and why is it significant?

Neuroligin-3 is a protein produced by neurons that supports neural communication. Glioma cells use it to grow. Blocking neuroligin-3 in mice halted tumor growth entirely, making it a powerful treatment target.

What is spatial transcriptomics?

It’s a method that combines microscopy and RNA sequencing to analyze gene expression in precise locations within a tumor. It allows scientists to identify where nerve-cancer interactions are most active.

Do peripheral cancers also use nerves to spread?

Yes. Lung, breast, and skin cancers have shown the ability to respond to neural signals, and in some cases, even adapt to resemble brain-like cells when spreading to the central nervous system.

Are there treatments targeting nerve-cancer interactions?

Experimental treatments are underway targeting proteins like PDGF and neuroligin-3. Some researchers are also exploring whether FDA-approved neural drugs could be repurposed to disrupt cancer-nerve communication.

What are the risks of targeting the nervous system in cancer therapy?

Because the nervous system regulates many vital functions, disrupting its pathways could lead to side effects like nerve damage or impaired organ function. Future therapies must balance cancer suppression with neural safety.

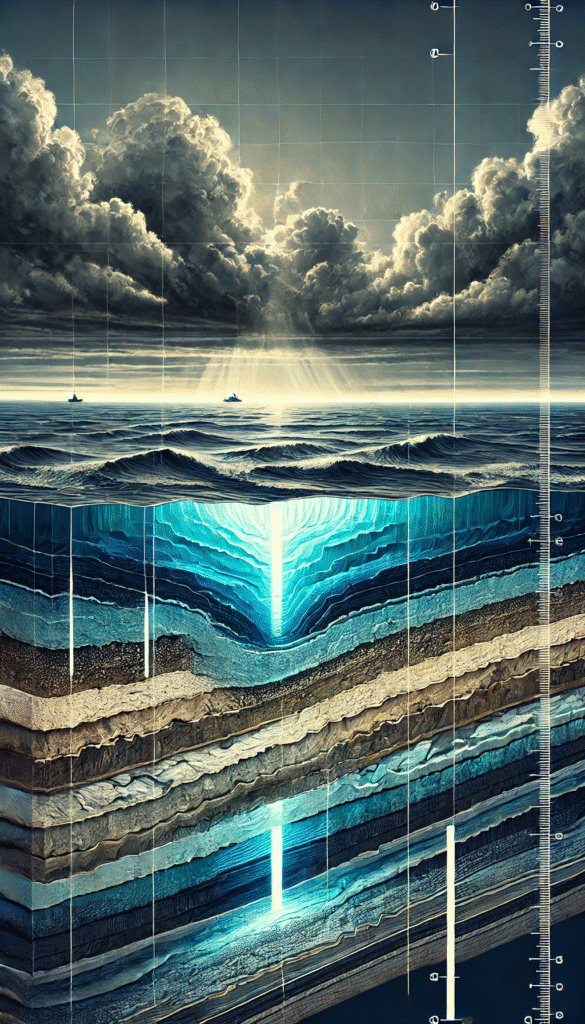

Mirror Life: Life in Reverse

ChatGPT:

Mirror Life: The Science, the Promise, and the Peril

I.

Foundations: Chirality and Life’s Molecular Logic

- Chirality refers to “handedness” in molecules—structures that are non-superimposable on their mirror image, like left and right hands.

- Life on Earth is fundamentally chiral:

- Amino acids used in proteins are all L-enantiomers (left-handed).

- Sugars in DNA/RNA are all D-enantiomers (right-handed).

- This homochirality is deeply consistent and crucial:

- Ensures uniform folding of proteins and functioning of enzymes.

- Enables the double helix structure of DNA to form correctly.

- Permits reliable recognition and interaction between molecules in cells.

- Although the opposite enantiomers—D-amino acids and L-sugars—do exist in rare natural contexts (e.g., in bacterial walls or aging tissues), they are not used in core life processes like protein synthesis or genetic encoding.

II.

Mirror Life: A Speculative Frontier

- Mirror life refers to organisms composed entirely of mirror-image biomolecules:

- D-amino acids instead of L.

- L-sugars instead of D.

- Left-twisted DNA instead of the natural right-handed helix.

- These hypothetical beings would be biochemically analogous to Earth life—but inverted in chirality.

- The idea challenges the notion that life must always follow Earth’s handedness.

- It’s a concept born from advances in:

- Synthetic chemistry (creating mirror molecules in the lab).

- Synthetic biology (assembling artificial systems from scratch).

- Astrobiology (considering alternative life forms elsewhere in the universe).

III.

Origins and Rationale for Exploring Mirror Life

- Why study mirror life?

- To understand how life might evolve with different chemical constraints.

- To explore why life chose one chirality over another—was it random or inevitable?

- To investigate biosafety and resilience: Could mirror biomolecules resist degradation, aging, or disease?

- To prepare for the detection of alien life, which might have the opposite handedness.

- To explore therapeutic applications, such as mirror peptides or mirror-DNA as drugs resistant to degradation.

- Louis Pasteur’s 19th-century discovery of molecular chirality laid the groundwork.

- He noticed that tartaric acid crystals separated into two mirror forms.

- Only one form rotated light and interacted with living organisms.

IV.

Scientific Progress Toward Mirror Systems

- Recent advances have produced:

- Mirror nucleic acids: L-DNA and L-RNA.

- Mirror proteins built from D-amino acids.

- Enzymes that can read and copy mirror-DNA (in very controlled systems).

- However, no self-replicating mirror organism yet exists.

- Scientists have not yet built a full mirror ribosome—the key to translating genetic code into proteins.

- The creation of autonomous mirror bacteria is still theoretical—but many believe it could be possible within a decade.

V.

The Promise: Why Mirror Biomolecules Matter

- Therapeutics and Diagnostics:

- Mirror-DNA and mirror-peptides are resistant to degradation by natural enzymes.

- Could be used to make long-lasting drugs, biosensors, or diagnostic tools.

- Already being explored in cancer therapy, gene regulation, and targeted imaging.

- Synthetic Biology:

- Mirror systems provide a clean slate for creating life-like systems without interfering with natural life.

- Could be used to build biological computers or molecular factories in confined settings.

- Astrobiology and Origins Research:

- Mirror life may help explain why terrestrial life is homochiral.

- If mirror life evolved independently elsewhere, it would confirm that life can emerge under radically different rules.

VI.

The Peril: Risks of Constructing Mirror Life

A.

Immune System Blindness

- Earth’s immune systems are highly chiral-specific.

- Antibodies, enzymes, and T-cell receptors are shaped to detect L-amino acid proteins and D-sugar-based DNA.

- A mirror organism would be:

- Invisible to the immune system.

- Resistant to degradation by natural enzymes.

- If a mirror microbe were released, it might infect and grow in hosts without triggering any immune defense.

B.

Antibiotic Resistance

- All known antibiotics and antimicrobial peptides are tailored to natural chirality.

- Mirror bacteria would be:

- Totally resistant to existing drugs.

- Unaffected by natural bacteriophages or microbial competition.

- This creates a situation where no known biological countermeasure would be effective.

C.

Ecological Invasion

- A mirror organism wouldn’t face natural predators, pathogens, or immune responses.

- It could:

- Thrive in niches where Earth organisms can’t compete.

- Exploit achiral or non-specific nutrients like carbon dioxide or phosphate.

- Potentially outcompete natural microbes if it gained replication competence.

D.

Biosecurity and Dual-Use Risks

- Mirror life research, especially for military or covert applications, has dual-use potential:

- Could be used to create undetectable biological agents.

- Would be immune to most current detection and treatment methods.

- The risk is magnified by:

- Increasing ease of DNA synthesis and protein engineering.

- Lack of regulatory frameworks specific to mirror systems.

VII.

The Precaution: What Scientists Are Calling For

In response to these concerns, leading synthetic biologists, immunologists, and ethicists (including authors of the Science article) recommend:

- Immediate moratorium on the creation of replicating mirror organisms.

- Especially those with functional mirror ribosomes and mirror genomes.

- Encouraging research on non-replicating mirror molecules:

- For medical and diagnostic applications.

- As they pose low risk and high benefit.

- Regulatory oversight:

- Establish monitoring of mirror-oligonucleotide synthesis.

- Classify mirror genome assembly and mirror ribosome engineering as high-security research areas.

- Develop global standards under the WHO or other international science governance bodies.

- Risk modeling and testing:

- Support studies on how mirror organisms might interact with Earth life.

- Develop mirror phages or enzymes as countermeasures, in case containment fails.

VIII.

Broader Reflections: What Mirror Life Teaches Us

- The very possibility of mirror life challenges our assumptions about biology’s inevitability.

- It pushes us to ask:

- Is life on Earth a frozen accident?

- Would alien life forms be fundamentally different—or similar with reversed handedness?

- Can we build alternative life responsibly, without repeating mistakes from other disruptive technologies?

- Mirror life is not just a scientific project—it is an ethical and existential test of our wisdom and foresight.

IX.

Conclusion: A Double-Edged Breakthrough

- Mirror life is one of the most intriguing and potentially transformative ideas in modern biology.

- It holds real promise in medicine, diagnostics, and origins research.

- But creating autonomous mirror organisms without clear safeguards is a risk with potentially global consequences.

Like a mirror, it reflects back at us not only life’s structural choices—but our own moral clarity.

Moonlight, Memory, and Music: Why Barcarolle Moves Us All

In a documentary about this Turner’s painting of Venice, Bacarolla is the background music, it really enhances the appreciation of the painting, explains from the perspective of neuroscience.

ChatGPT: The pairing of Offenbach’s Barcarolle with Turner’s painting “Venice Quay, the Riva degli Schiavoni” (1844) creates a multisensory experience that significantly enhances emotional and aesthetic appreciation—and neuroscience can explain why.

🧠 How the Brain Reacts to Art and Music Together

1.

Multisensory Integration – The Brain as a Synthesizer

- The superior temporal sulcus and posterior parietal cortex are responsible for combining different sensory modalities (vision + sound).

- When you look at Turner’s hazy, light-filled Venice while listening to the swaying rhythm of Barcarolle, your brain fuses the two into a single, enhanced emotional impression.

- This binding process deepens memory, mood, and meaning.

Result: You don’t just see the painting—you feel it move and breathe.

2.

Mirror Neurons and Emotional Resonance

- Music like Barcarolle activates mirror neuron systems, allowing the listener to empathize with the emotional tone of the song.

- The gentle duet creates a sense of intimacy and stillness, matching the soft dissolving forms in Turner’s painting.

- This alignment evokes a feeling of romantic reverie—as if one is drifting, both literally (on a gondola) and metaphorically (through time and memory).

The viewer’s brain mirrors the serenity and longing both in sound and image.

3.

Dopaminergic Reward Pathways – Pleasure in Harmony

- The mesolimbic system, especially the nucleus accumbens, releases dopamine in response to musical and visual beauty—especially when the two align in tone.

- Turner’s golden light, soft focus, and dreamy water reflections act like visual harmony.

- Barcarolle’s swaying rhythm and melodic consonance create auditory harmony.

When these harmonies match emotionally, your brain’s reward system lights up more intensely than for either one alone.

4.

The Default Mode Network (DMN) – Imagination and Memory

- Both Turner’s painting and Offenbach’s music invite internal wandering: romantic memory, daydreaming, fantasy.

- The DMN becomes active, linking the viewer’s personal memories of water, light, love—or imagined ones.

This mental drift amplifies the painting’s emotional pull beyond the visual.

5.

Temporal Entrainment – Barcarolle and the Gaze

- The 6/8 rhythm of the music subtly entrains the viewer’s attention: the eyes move more slowly, gently, in sync with the sway of the music.

- This slows perception, allowing the viewer to absorb Turner’s soft transitions and atmospheric dissolves more deeply.

The music paces the gaze, making the painting feel alive and cinematic.

🎨🎶 Conclusion:

Pairing Barcarolle with Turner’s Venetian mist and glimmer isn’t just poetic—it’s neuroaesthetic.

It works because:

- Both trigger parallel emotional circuits

- They entrain attention in a fluid, dreamlike rhythm

- The brain binds them into a single, emotionally heightened memory

You don’t just see Turner’s Venice—you float through it.

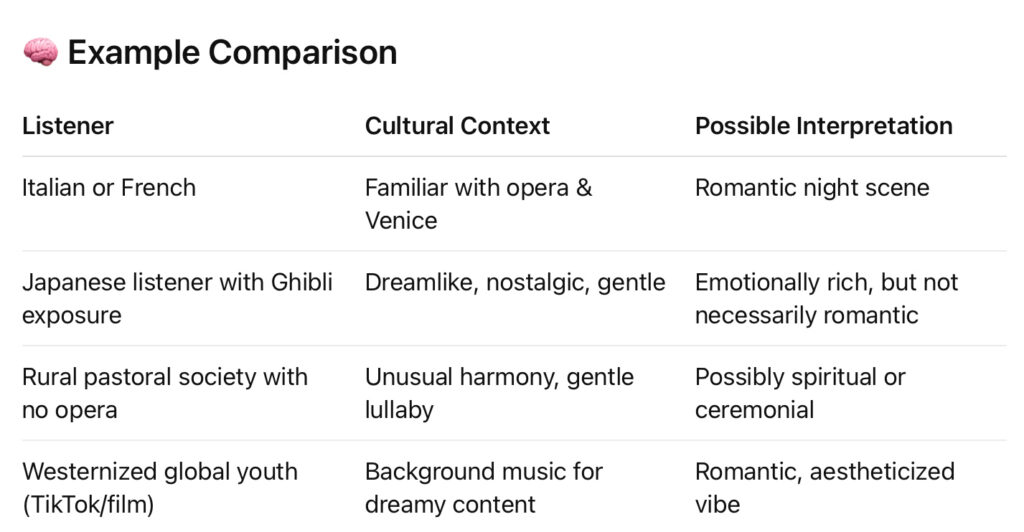

From the perspective of anthropology, how do people react without the pre-knowledge of Venice or the interpretation of song? Could they still feel the romantic connection? Or the reaction is pre determined by culture?

ChatGPT :

This is a profound and nuanced question. From the anthropological perspective, the answer lies at the intersection of universal human capacities and cultural conditioning.

🌍 Can people without pre-knowledge of Venice or the song still feel the romance?

Yes — to a degree.

But how they feel, interpret, or assign meaning to the feeling often depends on their cultural framework.

🧬 1.

Universals in Human Perception (Cross-Cultural Tendencies)

Anthropologists like Alan Lomax and ethnomusicologists like John Blacking showed that:

- Certain musical features (slow tempo, soft dynamics, harmonious intervals) are universally associated with calm, intimacy, and emotional depth.

- The lilting 6/8 rhythm of the Barcarolle mimics human movement—rocking a baby, swaying during courtship—which creates a somatic (bodily) sense of safety or tenderness.

- Vocal harmonization, especially female duets in thirds and sixths, can sound soothing or intimate across cultures—even when the language is unknown.

So yes, even without Venice or a translation, many listeners could feel that the song is “about love” or “about something beautiful and intimate.”

🌐 2.

But Meaning Is Filtered Through Culture

- In cultures that do not use Western tonality, the harmonic and melodic structure may not immediately signal “romance”—it might sound “foreign,” ceremonial, or neutral.

- Venetian gondolas, moonlit canals, European femininity are all Western cultural icons. Without those associations, the listener doesn’t imagine Venice—they imagine something else, or nothing at all.

- In some societies, romance is not publicly sung about; emotional restraint is more valued than expression. So the reaction may be aesthetic, but not personally romantic.

The emotion might be felt—but its interpretation depends on the cultural “lens.”

📖 3.

Cultural Scripts and Musical Semiotics

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote about how culture is a “web of meaning”. In music:

- We “read” songs through semiotic scripts (signs and meanings we’ve learned).

- The Barcarolle’s meaning in the West = “Venice + Night + Love”

But in another culture, the same sonority might signify ritual purity, mourning, or pastoral nostalgia.

🎵 Conclusion:

- Romantic response to the Barcarolle is partly universal (sound as feeling)

- But its meaning—Venice, love, night—is culturally coded

So people without pre-knowledge can feel, but what they think they’re feeling (and why) is largely a cultural construct.

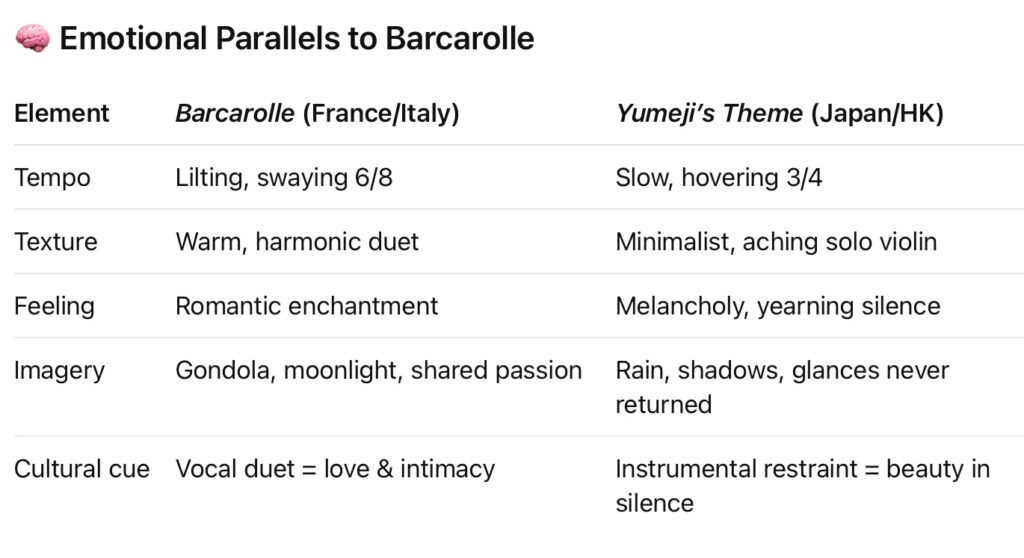

Let’s explore a non-Western musical piece that evokes similar dreamy or romantic emotions to Offenbach’s Barcarolle—but through entirely different musical structures and cultural meanings.

🎵 Example:

“Yumeji’s Theme”

from

In the Mood for Love

(2000)

Context: Accompanies scenes of unspoken love and emotional tension in Wong Kar-wai’s film

Composer: Shigeru Umebayashi

Origin: Japan/Hong Kong

Style: Slow, minor-key waltz with bowed strings and restrained phrasing

🔍 Anthropological Insight:

- In Barcarolle, love is sung, externalized, and illuminated by moonlight.

- In Yumeji’s Theme, love is withheld, internalized, and shaped by social norms of restraint—especially in traditional East Asian cultures where emotion is often expressed through subtle gestures rather than overt confession.

Yet both pieces stir the limbic system, and both evoke longing—but one expresses it as shared rapture, the other as quiet ache.

🎼 Other Non-Western Parallels

1.

North Indian Raga – Raga Yaman

- Played at twilight, often associated with love and yearning.

- Uses microtonal bends, drone accompaniment, and melodic improvisation to create a meditative emotional state.

- No harmony or fixed rhythm like Barcarolle, yet listeners often report feeling a sense of floating tenderness.

2.

Persian Classical Music – Dastgah Mahur

- Considered bright and lyrical—often performed on instruments like kamancheh or setar.

- The melodic lines unfold slowly, evoking subtle emotional colors without overt “romantic” cues.

- A poetic listener might still associate it with love or beauty, even if those aren’t culturally explicit.

🪞 Final Thought:

Across cultures, music can access shared human emotions, but each culture builds its own emotional language from those feelings.

- Barcarolle speaks in lyric beauty and shared love.

- Yumeji’s Theme whispers in silence and shadow.

- A raga or Persian melody blooms slowly, leaving room for inward meditation.

Romance, then, is a song the heart knows—but the world teaches us how to sing it.

Wired for Joy: The Future of Growing Older

ChatGPT:

Enhancing Joyspan through Digital Technologies: The Future of Aging Well

The aspiration for a long life has guided humanity for centuries, but modern discussions increasingly emphasize not merely extending lifespan or healthspan, but enriching the “joyspan,” a concept introduced by Kerry Burnight, a gerontologist who asserts that a meaningful life requires sustained joy and emotional fulfillment. Simultaneously, advancements in digital technologies provide unprecedented opportunities to foster happiness, leisure, social connection, and adaptability among aging populations. Merging the ideas from the “Joyspan” article and research from MDPI on digital enhancement reveals a comprehensive strategy for aging well in our rapidly digitalizing world.

Understanding Joyspan: The Art of Thriving

Burnight’s “Joyspan” philosophy pivots around four essential, nonnegotiable actions: Grow, Adapt, Give, and Connect. Each emphasizes active participation, emotional resilience, and positive engagement, promoting happiness irrespective of age or physical constraints.

Grow underscores continuous learning and curiosity, vital for cognitive health and emotional well-being. Examples from Burnight’s research highlight older adults undertaking new ventures, such as becoming substitute teachers post-retirement. This ongoing intellectual curiosity supports neural plasticity and provides purposeful enjoyment in later life.

Adapt highlights the critical skill of adjusting positively to inevitable life changes. Individuals who gracefully transition their activities—such as swapping in-person shopping for digital grocery services when physical mobility declines—demonstrate improved mental health and sustained happiness.

Give emphasizes that meaningful generosity, whether through teaching skills, volunteering, or simple kindness, deeply enriches emotional life and fosters a sense of purpose and community belonging.

Connect captures the essential nature of social bonds and relationships, underscoring the critical role of companionship, conversation, and communal activities in promoting mental health and overall happiness.

Burnight’s framework is validated extensively by gerontological research highlighting cognitive stimulation, adaptability, social engagement, and altruism as central to emotional well-being among seniors.

Digital Technologies: Enhancing Elderly Well-being

Complementing Burnight’s Joyspan, recent MDPI research examines how leisure and happiness correlate significantly among older adults, pinpointing key predictors of well-being, including leisure satisfaction, social companionship, and accessible community resources. Digital technologies increasingly play a critical role in enhancing these happiness factors, addressing barriers traditionally associated with aging.

Digital Access to Leisure and Satisfaction

Digital technologies provide elderly individuals with enriched leisure experiences, significantly boosting leisure satisfaction. Virtual reality (VR) technologies, online educational platforms, and interactive hobby-oriented communities can significantly enhance seniors’ quality of life. For instance, seniors participating in online courses or virtual travel experiences report elevated levels of curiosity and joy, directly aligning with Burnight’s growth principle. Platforms offering remote engagement, such as virtual museum tours or online hobby groups, effectively circumvent physical limitations while fostering continuous cognitive and emotional stimulation.

Adaptability through Digital Solutions

The capability to adapt gracefully to life changes is crucial to maintaining happiness as individuals age. Digital innovations offer seniors adaptable alternatives to traditional activities, ensuring continuous participation despite physical or cognitive decline. Seniors who struggle with mobility issues can transition smoothly from physically demanding hobbies, such as hiking or running, to digitally facilitated alternatives, including exergaming or fitness tracking apps tailored specifically to their needs. Similarly, the shift from traditional book reading to audiobooks or digital reading platforms effectively addresses declining eyesight without compromising the joy of engaging with literature.

Generosity and Digital Giving

Digital technologies also enhance opportunities for seniors to give meaningfully. Online platforms such as AARP’s Create the Good program match senior volunteers with suitable opportunities, increasing their ability to contribute positively to their communities from home. Digital volunteering, mentorship programs, or community forums enable older adults to share their wisdom, experiences, and skills effortlessly and conveniently. These digital opportunities amplify the potential for older adults to achieve emotional fulfillment through meaningful generosity and communal contributions.

Strengthening Social Connections Digitally

The MDPI research emphasizes the substantial correlation between social connectivity and elderly happiness. Digital technology bridges gaps caused by geographical distance, mobility issues, or isolation. Platforms enabling easy video conferencing, virtual game nights, or shared multimedia experiences have become indispensable in maintaining and expanding social bonds. Burnight notes the significance of maintaining relationships actively, and digital platforms substantially simplify initiating and maintaining these connections. Seniors who regularly interact digitally with friends, family, or social groups report lower feelings of isolation and enhanced emotional resilience.

Digital Inclusion and Bridging the Technological Gap

To effectively harness digital technology’s full potential in promoting Joyspan, addressing digital exclusion becomes paramount. Barriers including digital illiteracy, lack of accessibility, and inadequate infrastructure disproportionately affect older adults, limiting their ability to benefit fully from technological advancements. Addressing this through senior-friendly designs, intuitive interfaces, assisted technology training programs, and supportive public policies can dramatically expand digital inclusion, ensuring equitable happiness benefits across socio-economic and geographical boundaries.

Augmented Reality (AR)-enabled tutorials and simplified mobile platforms have been successful in improving older adults’ technological comfort, empowering them to integrate digital solutions effectively into their daily lives. Communities and policymakers must prioritize programs addressing digital gaps, facilitating broader access to these critical happiness-enhancing tools.

Ethical Considerations and Privacy

Integrating digital solutions in elder care also necessitates careful consideration of ethical implications, particularly data privacy and consent. Ensuring transparent, user-controlled data management systems strengthens trust among older adults, alleviating concerns that might otherwise discourage technological adoption. Digital ethics frameworks focusing specifically on elder care settings could guide responsible technology integration, addressing concerns proactively and enhancing seniors’ confidence in using digital platforms extensively.

Emerging Frontiers: IoT, AI, and Digital Twins

The future promises even more sophisticated digital innovations with significant potential for elder well-being. Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled home environments enhance independent living by providing seniors with real-time safety and health monitoring, enabling safe leisure participation without constant supervision. Digital twins—virtual models that replicate seniors’ environments to optimize their living conditions—are emerging as powerful tools for personalized, adaptive living support, integrating seamlessly with seniors’ daily routines and enhancing their overall well-being and happiness.

Artificial intelligence (AI)-driven personalized assistance platforms further complement Joyspan principles, offering tailored leisure and learning experiences, personalized health advice, and predictive tools to enhance adaptability and resilience proactively.

Implementing an Integrated Approach

A combined strategy integrating Burnight’s Joyspan model with digitally-enhanced leisure and social frameworks offers a holistic approach to aging happily and meaningfully. Practical applications include:

- Community digital hubs offering accessible training and support.

- Virtual leisure networks encouraging lifelong learning and cognitive engagement.

- Adaptive digital leisure solutions tailored to individual physical and cognitive capabilities.

- Digital platforms promoting intergenerational exchanges, mentorship, and meaningful volunteering.

- Policy initiatives supporting equitable digital infrastructure, targeted specifically towards aging populations.

Conclusion: Digital Joyspan as a Pathway Forward

The synergistic potential of Joyspan and digital technologies signals a promising evolution in aging experiences. By proactively leveraging technology to facilitate learning, adaptability, generosity, and social connection, societies can profoundly enhance older adults’ emotional and psychological well-being. As we continue to embrace technological advancements, the essential goal remains clear: to ensure that longevity is not just about adding years to life, but genuinely adding joyful, meaningful life to those years.

Canal-gebra: Solving for Chaos

ChatGPT:

Title:

“From Steering Wheel to Tillering Fiasco: A Guide to the Glorious Misery of Driving a Barge in France”

Or: How to Go from Linear Logic to Nonlinear Regret in 68 Locks or Less

INTRODUCTION: LINEAR EXPECTATIONS, NONLINEAR HUMILIATION

Let’s start where your journey began—in a car. A beautiful, obedient machine that does exactly what you ask of it (except parallel parking). You turn the wheel a little, the car turns a little. You turn it more, the car turns more. That’s a linear system—predictable, friendly, basically the golden retriever of physics.

And then one day you think, “What if I drove a barge in France?”

This is where the wheels fall off—metaphorically, of course, since barges don’t have wheels, just your shattered expectations drifting downstream.

Driving a barge is not like driving a car. It’s not like driving anything. It’s like writing a strongly worded letter to the water and hoping it eventually obeys. This, dear reader, is your introduction to nonlinear systems, canal-based suffering, and the extremely avoidable chaos of self-driving holidays in French inland waterways.

CARS: SIMPLE MACHINES FOR SIMPLE JOYS

Before we throw you in the canal of consequences, let’s appreciate the simplicity of your car:

- You steer left → it goes left.

- You stop accelerating → it slows down.

- You hit the brakes → it stops (shockingly useful).

- You arrive on time, in control, with dry shoes.

All this is possible because the mechanics of driving a car are linear:

- Inputs and outputs scale predictably.

- You control the direction directly.

- There’s friction with the road.

- Newton’s laws behave themselves.

Driving a car makes you feel competent.

Driving a barge makes you question your life choices.

BARGES: GIANT, FLOATING MATH JOKES

Now enter the barge—a vehicle that does not obey logic, gravity, or your shouted instructions.

Let’s clarify something: you don’t “drive” a barge. You negotiate with it. Slowly. Desperately.

Here’s why barges are textbook nonlinear systems:

1.

Delayed Response

You steer—and nothing happens. Then, after a suspenseful pause, it turns way too much. Then you overcorrect. Then that overcorrects. You’re now spinning. Congratulations: your barge is doing interpretive dance.

2.

Momentum from Hell

Your barge is 50 feet long, made of steel, and weighs more than your self-esteem. Once it’s moving, it does not want to stop. No brakes. You slow down with reverse thrust and prayers.

3.

Wind is Your Enemy

A mild breeze will push your barge diagonally into the bank like a bored toddler swatting a toy. Any side wind turns your entire vessel into a sluggish kite.

4.

Rudder-based steering

You don’t steer the barge itself. You redirect water, and the water slowly nudges the stern, which slowly swings the front, which slowly turns the barge. All of this happens just slowly enough for you to think nothing’s happening—until it’s too late.

THE UNFORESEEN HAZARDS OF THE FRENCH CANAL SYSTEM

You thought, “Ah, France. Wine. Cheese. Floating gently past castles.”

And you were wrong.

⚠️

Locks. So Many Locks.

Some canals—like the infamous Canal de Bourgogne—have 60+ locks per week. Each one is a hydraulic mood swing that requires:

- Tying ropes in a panic

- Shoving the barge off walls with a boat hook

- Screaming “IS IT OPEN YET?”

- Possibly launching a crew member into the water (accidentally)

⚠️

Wind from the Mediterranean

On canals like the Rhône à Sète, sea winds slam into your barge like an air-powered slapstick routine. You’ll try to steer forward and end up on the wrong bank, angled like you’re ashamed of your own trajectory.

⚠️

Overconfident Crew

There’s always a retired navy captain who says, “We can go faster.”

There’s always someone who thinks “mooring next to a lock during lunch” is safe.

There’s always a tech guy who can code in 14 languages but uses a mooring pole like a catapult.

HOW TO ACTUALLY STEER A BARGE (WITHOUT BECOMING A TRAGIC MEME)

📍 Before You Start:

- Assign roles. Someone steers. Someone mans the ropes. Someone points at ducks.

- Check wind conditions. If trees are moving, your barge will too.

- Test your tiller. Left is right. Right is left. This is not a metaphor.

📘 THE BARGE STEERING MANUAL (with Sarcasm-Free Translation)

STEP 1:

Throttle is your lifeline

- Always steer with some forward momentum. No speed = no rudder control.

- Reverse = your brake. Use it early and gently.

STEP 2:

To turn left, push the tiller right

- This moves the back of the barge right, swinging the front left.

- WAIT. Let the barge respond. Do not wiggle it like a Wii controller.

STEP 3:

Wind management

- Point the bow slightly into the wind to counter sideways drift.

- If you drift too much, stop everything. Reposition slowly.

- Side wind? Expect to hit the bank at least once. Just pretend it was on purpose.

STEP 4:

Approaching a lock

- Slow down way earlier than feels necessary.

- Come in at an angle—line up as you enter.

- Throw mooring lines to your rope guy (hopefully not the one who fell in last time).

- Reverse gently to halt inside the lock.

STEP 5:

Mooring like a civilized person

- Use two mooring lines minimum.

- Hammer poles fully into the bank (not just half-hearted taps).

- Never moor next to an active lock. Just don’t. Trust us.

STEP 6:

Turning Around (God Help You)

- Use reverse and full rudder in open canal sections only.

- Accept that it will take three tries and half your pride.

PRO TIPS (FROM PEOPLE WHO SURVIVED)

- Bring gloves. Rope burn is not romantic.

- Assign designated sober crew during lunch stops.

- Carry a boat hook—for pushing off the bank and fishing out crew members who “slipped.”

- Respect the 8 km/h limit. It’s not a suggestion. It’s a physical law of barge equilibrium.

- Don’t fight the barge. Think like a barge. Slow. Heavy. Majestic. Confused.

FINAL THOUGHTS: YOU’LL SURVIVE (PROBABLY)

You’re not just on vacation. You’re taking part in a centuries-old dance of water, physics, and human misjudgment.

Will you drift?

Yes.

Will you spin?

Almost definitely.

Will you moor perfectly?

No, but you’ll lie about it later.

And one day, after the blisters have faded and the wine has worn off, you’ll find yourself at a dinner party, swirling your glass, and someone will say,

“Didn’t you do a barge trip in France?”

And you’ll smile and reply:

“Ah yes. We lost an anchor. Nearly overtook a nun’s barge. Pushed a CEO into the canal. It was wonderful.”

And that, my friend, is barge life.

Suggested reading:

- “Zen and the Art of Not Overcorrecting”

- “Advanced Rope Tossing for Business Executives”

- “How Not to Blame the Wind (Even Though It Was Definitely the Wind)”

Decode Your Decisions

ChatGPT:

Thinking, Fast and Slow

by Daniel Kahneman

Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow is a groundbreaking exploration of how the human mind works, focusing on the dual systems of thinking that drive our decisions. It combines decades of research in psychology and behavioral economics to reveal the cognitive biases and heuristics that affect our judgment.

🎯 Conclusion

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman explains that our minds operate through two systems: System 1, which is fast, intuitive, and emotional, and System 2, which is slower, deliberate, and logical. Most of our daily decisions rely on System 1, making us vulnerable to errors in judgment. Kahneman presents compelling experiments and studies showing how this reliance leads to biases like loss aversion, framing effects, and overconfidence. He challenges the assumption of human rationality in economics, showing that we often act against our best interests due to flawed thinking patterns. The book closes with reflections on how to guard against these biases, even though eliminating them completely is impossible. Overall, it’s a powerful call for self-awareness and better decision-making through understanding our mental shortcuts.

🧠 Key points principales

🧩 System 1 and System 2: Our brain runs on two modes—fast, automatic thinking and slow, effortful reasoning.

💡 Cognitive biases: We’re prone to systematic errors, like anchoring, availability heuristics, and the halo effect.

📉 Loss aversion: Losses feel twice as painful as gains feel good, skewing risk assessment.

📊 Framing effects: The way a choice is presented dramatically changes how we perceive it.

👁️ WYSIATI (What You See Is All There Is): We make decisions based only on the information immediately available, ignoring what’s missing.

🧠 Substitution: When faced with a hard question, we often answer an easier one without realizing it.

🔢 Base rate neglect: We ignore statistical realities in favor of vivid personal anecdotes or stereotypes.

🗣️ Overconfidence bias: People consistently overestimate their knowledge and predictions.

📉 Regression to the mean: Extreme outcomes tend to be followed by more average ones, yet we often misattribute the change.

🧪 Prospect Theory: A cornerstone of behavioral economics explaining how people evaluate potential losses and gains asymmetrically.

📚 Summary resumido

- Two Systems of Thinking: Kahneman describes System 1 as fast, automatic, and emotional, while System 2 is slow, analytical, and effortful. Most decisions are unconsciously made by System 1, with System 2 intervening only when necessary.

- Heuristics and Biases: We rely on mental shortcuts to make decisions quickly, but these often lead to predictable biases such as the anchoring effect and availability heuristic.

- Overconfidence and Intuition: People often trust their gut feelings even when these are based on flawed reasoning. Kahneman shows how confidence is a poor indicator of accuracy.

- Loss Aversion: People react more strongly to losses than to equivalent gains. This bias heavily influences financial and personal decisions.

- Framing Effects: The way information is presented can influence decisions more than the content itself—for example, “90% survival rate” sounds better than “10% mortality rate.”

- The Illusion of Understanding: We construct coherent narratives around past events, giving us false confidence in our knowledge and predictions.

- Intuition vs. Expertise: Genuine expertise requires an environment with regular patterns and feedback. In many areas, intuition is no better than chance.

- Prospect Theory: Co-developed by Kahneman, it refutes classical economic models by showing that people value gains and losses differently, leading to irrational choices.

- The Planning Fallacy: People systematically underestimate the time, costs, and risks of future actions and overestimate the benefits, leading to overly optimistic plans.

- Experiencing Self vs. Remembering Self: Kahneman distinguishes between the part of us that experiences life moment by moment and the one that remembers and judges it, which often misrepresents reality.

📌 Quotes from

Thinking, Fast and Slow

by Daniel Kahneman

Here are some of the most powerful and insightful quotes from the book, capturing its key ideas and wisdom for life and decision-making:

- “Nothing in life is as important as you think it is, while you are thinking about it.”

– A reminder of how our attention skews our perception of importance. - “We are prone to overestimate how much we understand about the world and to underestimate the role of chance.”

– On the illusion of understanding and randomness. - “The confidence people have in their beliefs is not a measure of the quality of evidence but of the coherence of the story the mind has managed to construct.”

– Confidence is often misleading. - “What you see is all there is.”

– The WYSIATI principle: We base decisions on available information, ignoring what we don’t see. - “The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained.”

– On hindsight bias and narrative fallacy. - “Losses loom larger than gains.”

– The core idea of loss aversion in Prospect Theory. - “A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth.”

– The danger of repeated misinformation. - “We can be blind to the obvious, and we are also blind to our blindness.”

– The limits of self-awareness. - “Intuitive errors are not restricted to the intellectually limited. They are not a feature of irrationality, but of the workings of normal cognition.”

– Everyone is susceptible to biases, regardless of intelligence. - “Expert intuition strikes us as magical, but it is not. It is recognition.”

– The truth behind intuition: pattern recognition in consistent environments. - “The experiencing self does not have a voice. The remembering self is sometimes wrong, but it is the one that keeps score and makes the decisions.”

– On how memory shapes our life choices. - “You are more likely to learn something by finding surprises in your own behavior than by hearing surprising facts about people in general.”

– Self-awareness as a learning tool. - “Optimistic bias may well be the most significant of the cognitive biases.”

– On why we often misjudge risk and overestimate success. - “People tend to assess the relative importance of issues by the ease with which they are retrieved from memory—and that is largely determined by the extent of coverage in the media.”

– Media’s role in shaping perception. - “An individual who expresses high confidence probably has a good story, not necessarily a good understanding.”

– Confidence ≠ competence.

❓Frequently Asked Questions about

Thinking, Fast and Slow

What is the central idea of

Thinking, Fast and Slow

?

The book explores how the human brain uses two systems of thinking: System 1 (fast, intuitive) and System 2 (slow, deliberate). Kahneman shows how most decisions are made by System 1, leading to predictable cognitive biases.

Who is Daniel Kahneman?

Daniel Kahneman is a Nobel Prize-winning psychologist known for his work in behavioral economics, especially on judgment, decision-making, and cognitive biases. He co-developed Prospect Theory with Amos Tversky.

What is System 1 thinking?

System 1 is fast, automatic, emotional, and subconscious. It helps us handle everyday tasks efficiently but is prone to errors and biases due to its reliance on intuition and shortcuts.

What is System 2 thinking?

System 2 is slow, effortful, logical, and conscious. It’s responsible for deep thinking, analysis, and complex decisions—but it’s lazy and often lets System 1 take over.

What is the Prospect Theory?

Prospect Theory explains how people evaluate risk and reward. Unlike classical economics, it shows that losses feel worse than equivalent gains, leading people to make irrational decisions under uncertainty.

What is “loss aversion”?

Loss aversion refers to the idea that people feel the pain of losses about twice as strongly as the pleasure of gains. This bias explains why we often avoid risk, even when the potential benefits outweigh the costs.

What does “What You See Is All There Is (WYSIATI)” mean?

WYSIATI is the principle that people make judgments based on the information available to them, ignoring missing or unknown data. It leads to overconfidence and flawed reasoning.

Why is intuition often unreliable?

Intuition relies on pattern recognition and works well in stable environments with frequent feedback. In unpredictable domains (like investing or hiring), intuition often fails due to bias and noise.

How does the book explain overconfidence?

Kahneman shows that confidence does not correlate with accuracy. People often overestimate their knowledge, skills, and predictions, leading to bad decisions—especially in complex or uncertain environments.

How can I apply this book in real life?

Use System 2 thinking for important decisions, be aware of cognitive biases, seek diverse perspectives, and use data-driven approaches like reference class forecasting. Awareness of these tendencies can help reduce error and improve judgment.

Trust, Tricks & Transactions

ChatGPT:

Hidden Conflicts in Finance

This lecture by Professor Raghavendra Rau (Cambridge University) inaugurates a series exploring the human side of finance. It delves into how promises—central to financial contracts—are valued, and the often-hidden conflicts embedded in financial systems, especially those arising from principal-agent dynamics, intermediaries, and the emergence of private money like stablecoins.

🎯 Conclusion

Finance, at its core, revolves around valuing promises—whether from companies, governments, or individuals—and managing the conflicts that arise from these promises. While classical finance assumes rational markets, the human side introduces behavioral and structural problems, most notably principal-agent conflicts. These conflicts arise when those entrusted to act on behalf of others (agents) may have diverging incentives from the principals they serve. Financial intermediaries, such as banks and mutual funds, play crucial roles but can also harbor hidden risks. The rise of stablecoins mirrors historical patterns in private money but raises new regulatory concerns. Ultimately, although financial systems have evolved with more formal contracts and regulations, they remain susceptible to asymmetry, behavioral biases, and complexity-driven conflicts.

🔑 Key points

📜 Finance = Promises: Financial instruments are built on promises to pay or deliver future value in exchange for money today.

⚖️ Two valuation lenses: Classical finance values using data and models; behavioral finance considers human biases and trust.

🧑💼 Principal-agent problem: When agents (executives, fund managers, etc.) act on behalf of principals (investors) but have conflicting interests.

🏦 Banks’ core roles: Banks act as matchmakers, risk managers, liquidity providers, and information processors in the economy.

📉 Bank runs: Triggered by fear, bank runs reveal vulnerabilities in the mismatch between short-term liabilities and long-term assets.

🔐 Implicit contracts: Trust-based unwritten agreements—common in long-term or high-trust relationships—can substitute for rigid contracts.

💵 Stablecoins: Cryptocurrencies pegged to fiat currencies function like banks but with looser regulation and greater run risk.

🌐 Eurodollar market: A massive, loosely regulated offshore dollar system (~$12.8 trillion) that complicates monetary control.

📊 Regulatory gaps: Financial innovations often outpace oversight, as seen with crypto and DeFi, creating new risks.

🧠 Behavioral economics: Even rational-looking systems are shaped by psychology, herd behavior, and information asymmetry.

🧠 Summary

- Finance as promises: Finance is based on exchanging money now for future commitments (stocks, bonds, insurance). Two major perspectives assess these promises: rational valuation and human behavior.

- Human side of finance: Market behavior is affected by trust, incomplete contracts, and the potential for fraud, complicating valuation and decision-making.

- Role of financial intermediaries: Banks and funds reduce transaction costs, offer liquidity, transform maturity, and assess risk on behalf of individuals and businesses.

- Principal-agent problem: Occurs when those making decisions (agents) have incentives that diverge from those providing the capital (principals), evident across finance, real estate, and politics.

- Mechanisms to control agents: Contracts, legal regulations, and reputational dynamics are used to align interests, though none are foolproof.

- Value of implicit contracts: In trust-based or flexible settings, unwritten rules (e.g., job security or customer loyalty) can be more effective than formal agreements.

- Bank functions and profits: Banks profit from interest spreads, maturity transformation, and payment facilitation. Their lending increases money supply.

- Preventing bank runs: Tools include deposit insurance, capital and liquidity requirements, and central bank backstops. Yet digital finance introduces new risks.

- Rise of stablecoins: Digital fiat-pegged currencies like USDC and USDT operate like banks but lack full regulation, risking modern “crypto runs.”

- Global money creation: Commercial banks—not central banks—create most money through lending. The Eurodollar market further complicates global financial control.

*********

What is the principal-agent problem in finance?

The principal-agent problem arises when one party (the principal) hires another (the agent) to act on their behalf, but the agent’s interests may not align with the principal’s. For example, shareholders expect CEOs to maximize shareholder value, but CEOs might prioritize personal benefits instead.

How do financial intermediaries like banks add value to the economy?

Banks match savers with borrowers, transform short-term deposits into long-term loans, manage and spread risk, produce financial information, and provide liquidity. These functions enable efficient capital allocation and smoother economic activity.

What mechanisms exist to control agents in financial relationships?

Controls include explicit contracts (e.g., performance-linked pay), legal regulations (e.g., fiduciary duties, financial disclosure laws), and implicit contracts based on reputation and repeated interactions. A mix of these methods is often used.

Why are implicit contracts important in finance?

Implicit contracts are unwritten understandings based on trust, commonly found in long-term business relationships, mentorships, or professional services. They offer flexibility where formal contracts are too rigid or costly to enforce.

What causes bank runs, and how can they be prevented?

Bank runs occur when depositors withdraw funds en masse, fearing bank insolvency. Preventive measures include deposit insurance, capital and liquidity requirements, and central banks acting as lenders of last resort.

How do banks make money?

Banks earn through the interest rate spread—paying lower interest on deposits than they charge on loans. They also profit from fees, investment returns, and money creation via lending (the money multiplier effect).

What are stablecoins, and why are they significant?

Stablecoins are cryptocurrencies pegged to traditional currencies (like the US dollar) to maintain price stability. They facilitate fast digital transactions but carry risks due to lack of regulation and reserve transparency.

How does the Eurodollar market affect global finance?

The Eurodollar market involves U.S. dollars held in foreign banks, creating a parallel financial system. With an estimated size of $12.8 trillion, it influences global interest rates and undermines centralized monetary control.

Do central banks control the money supply?

Not entirely. Most money is created by commercial banks through lending. Central banks influence money supply indirectly through interest rates and reserve requirements but don’t directly control all money creation.

How has finance changed in the modern era?

Finance has shifted from trust-based local systems to global, regulated, and digitized networks. Despite formalization, new conflicts and asymmetries have emerged due to complexity, technology, and information gaps.

🎯 Key Takeaways (a.k.a. things you should know but probably won’t remember):

1.

Finance = Promises. Promises = Risk.

From stocks to insurance, everything is built on promises for future payouts. The real game is figuring out if the people making those promises are lying, stupid, or both.

2.

Classical vs. Human Finance:

- Classical finance is the MBA fan fiction version: efficient markets, DCF models, and spreadsheet-induced confidence.

- Human finance is actual reality: deception, incomplete contracts, asymmetric information, and the persistent hope that your fund manager isn’t just chasing his quarterly bonus.

3.

Principal-Agent Problem:

This is the academic way of saying: “People paid to act on your behalf often do what’s best for them instead.”

- CEOs redecorate their egos with shareholder money.

- Fund managers swing for the fences to earn bonuses.

- Politicians forget your name right after elections.

It’s like hiring a dog to guard your sandwich.

4.

Financial Intermediaries Are Supposed to Help…

…but they also create massive conflict potential. They:

- Match savers and borrowers (useful).

- Transform short-term deposits into long-term loans (risky).

- Manage risk via pooling (debatable).

- Pretend to be experts with your money (sometimes true).

- Add liquidity… until they don’t.

5.

Banks Are Giant Risk Factories:

They create money by lending more than they have. They profit from the interest rate spread, and when things go bad, they get government bailouts because… well, capitalism but make it inconsistent.

6.

Bank Runs: Still a Thing!

Northern Rock, Silicon Valley Bank, etc.—they prove we haven’t learned anything. Deposit insurance exists to calm the peasants, but moral hazard lives rent-free in boardrooms.

7.

Stablecoins: Crypto’s Weird Banking Cosplay

- Pretend money backed by maybe-money.

- Still prone to runs (TerraUSD says hi).

- Poorly regulated but highly influential.

- If they collapse, we all get to pretend we didn’t see it coming.

8.

The Money Supply Isn’t Really Controlled by the Central Bank:

Shocking, I know. Most money is created by commercial banks via lending. The Fed adjusts interest rates, but the Eurodollar market operates like a drunk cousin who can’t be grounded because he lives abroad.

🧠 Financial Advisor Commentary:

This lecture is an important reminder for investors, analysts, and regulation fetishists alike: finance is fundamentally human, and therefore fundamentally flawed.

The more layers you build to protect against risk—legal contracts, regulation, performance metrics—the more creative people get at exploiting loopholes. Even well-meaning systems eventually become bureaucratic mazes or tools of manipulation.

As a senior financial advisor, I’d say this lecture is a must-read for anyone who thinks compliance and modeling are enough. It reminds you to look behind the curtain, question the incentives, and not assume your fiduciary actually remembers what that word means.

🔚 Bottom Line:

You want safety? Buy Treasury bonds. You want real financial insight? Understand human behavior, not just spreadsheets. And maybe don’t trust a stablecoin named after a Roman god if you’re storing your retirement in it.

Now or Never: Time, Culture, and Control

ChatGPT:

We race through hours like coins tossed in a well,

Each task a bell that tolls for vacant gain.

Our calendars, like prisons, falsely tell

That movement soothes the soul or dulls the pain.

But speed is not a sign the heart is full,

Nor is the climb a proof the peak was meant.

The busiest hands may craft a life that’s dull,

The swiftest feet may pass what life once lent.

To chase is not to cherish—know the space

Where stillness holds more weight than frantic stride.

The root grows not in motion, but in place;

The truth is not in forward, but inside.

So pause—before you crown the clock as king,

And ask what meaning all this pace might bring.

**************

Title: “The Only Time I Have Is Now”: Sociological and Cultural Perspectives on Time

“I don’t know how many days, how many minutes or seconds left—the only time I have is now, this moment.”

This sentiment, seemingly personal and reflective, echoes a deeper philosophical and sociological truth: our understanding of time is not universal, fixed, or objective. Rather, time is a constructed experience—shaped by emotion, culture, power structures, and technology. It is one of the few constants in life that is experienced so inconsistently.

Sociologically, time is not merely a neutral backdrop for human action. Instead, it is a resource, a battleground, a form of control, and sometimes even a tool of oppression. In many Western societies, time is treated as a commodity to be spent, saved, or wasted. The minute hand doesn’t just move—it ticks with economic, social, and moral implications.

Time as a Social Construct

Sociologists have long argued that time is socially constructed—that is, its meaning and structure are shaped by human practices and cultural norms rather than any intrinsic property of the universe. E.P. Thompson, in his influential work Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism (1967), explored how the Industrial Revolution fundamentally altered people’s experience of time. Prior to industrialization, time was measured in tasks and natural cycles: you worked until the work was done, not until the bell rang. But with the rise of capitalism came the standardization of time, enforced by factory whistles and mechanical clocks.

This shift was not just technological—it was moral and ideological. Punctuality became a virtue, lateness a vice. Time was no longer a shared experience—it became a metric for productivity and a weapon of discipline. To be late was not just to miss an appointment; it was to violate a social code rooted in economic utility.

And we have inherited this moral economy of time. Contemporary life is full of language that reflects our relationship with time as a finite resource: we “spend” time, we “waste” it, we’re always “running out.” Yet ironically, in this supposed age of hyper-efficiency, we increasingly report feeling short on time. Sociologist Judy Wajcman calls this phenomenon “temporal dissonance”: the more we try to master time with digital calendars, productivity hacks, and 15-minute task lists, the more time seems to slip away from us.

Temporal Inequality

Another vital contribution of sociology is the recognition of temporal inequality. Not everyone has the same access to time. The rich can buy time—through housekeepers, nannies, drivers, and personal assistants. The poor often sell their time through wage labor, shift work, or gig economy tasks. Time, like money, is unevenly distributed.

This disparity also has a gendered dimension. Arlie Hochschild’s concept of the “second shift” reveals how women, even when employed full-time, often carry the burden of domestic labor after hours. So while a man may come home and enjoy “free time,” a woman may begin her unpaid second job as a caregiver, cleaner, and emotional manager. In this sense, time is not just measured in hours—it is measured in agency.

Acceleration and Modern Life

Sociologist Hartmut Rosa takes the critique of modern temporality a step further. In his theory of social acceleration, Rosa argues that technological, social, and economic systems are locked in a cycle of increasing speed. Faster communication, faster transport, faster lives. But paradoxically, this acceleration does not give us more time—it increases pressure, fragmentation, and the feeling that life is rushing past us.

Even leisure is infected by the tempo of acceleration. Vacations are planned with military precision, “self-care” is squeezed into 10-minute mindfulness apps, and sleep becomes a performance metric tracked by wearable devices. We have not escaped industrial time—we’ve digitized it and put it in our pockets.

Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Time

If sociology shows how time is constructed and stratified, cultural philosophy reveals how diverse those constructions can be. Different societies don’t just experience time differently—they conceptualize it in fundamentally contrasting ways.

Western Linear Time

Most Western cultures operate on a linear model of time: past, present, future. Influenced by Judeo-Christian theology, Enlightenment rationalism, and capitalist logic, this perspective views time as a progression. Life moves in a straight line—toward salvation, success, or retirement. This view favors planning, goals, and historical causality.

St. Augustine famously wrote about the puzzling nature of time in Confessions, noting that we remember the past, experience the present, and anticipate the future—but we do so all in the present. In a way, even the linear perspective admits that all time is, ultimately, now.

Indigenous and Cyclical Time

In many Indigenous cultures, time is not linear but cyclical or event-based. For example, in Australian Aboriginal traditions, the concept of Dreamtime transcends Western notions of chronology. It is not “long ago,” but a simultaneous, ever-present spiritual reality. In Native American and Andean worldviews, events are often understood in cycles tied to nature, ritual, and communal memory. Time here is relational and sacred, not something to be “used” but something to be lived within.

East Asian Temporal Philosophies

Daoism and Zen Buddhism also diverge from linear time. In Daoism, time is like water: flowing, unpredictable, and inherently meaningless unless aligned with the Dao, or the natural way. Rather than resist time, one should move with it. Zen Buddhism emphasizes mindfulness of the present moment, not because the future is irrelevant, but because attachment to past or future leads to suffering. Time is not the enemy—it is illusion, and enlightenment lies in transcending it.

African Event-Based Time

In many sub-Saharan African societies, time is understood through events and relationships rather than fixed schedules. Kenyan philosopher John Mbiti argued that time is “two-dimensional,” focused on the present and the past, with the future being vague and less emphasized. Events happen “when the people are ready,” not when the clock strikes. Here, time supports human needs, rather than demanding human efficiency.

The Moment We Have

So when someone says, “The only time I have is now,” they’re not just being poetic. They are, perhaps unknowingly, rejecting capitalist time, challenging linearity, and joining a chorus of traditions that prioritize presence over progress, being over doing.

From a sociological angle, this statement can be read as a rebellion against temporal discipline—a refusal to be commodified. From a cultural perspective, it is an affirmation of the lived, the sacred, the real.

The moment—this strange, elusive slice of being—is the one thing we all possess, even if just for a flicker. And yet, in chasing time, we often lose it. Philosophy and sociology together remind us that perhaps the most radical act in modern life is not to save time, but to experience it fully.

Because no one can say how many minutes or seconds are left. But the moment you’re in? That’s the one you own.

Your Golden Years Have Two Price Tags — Plan for Both

ChatGPT:

The Retirement Mirage: Why Your Financial Plan Needs Two Phases — And How to Prepare for Both

Most retirement planning conversations begin with hopeful visions of long-delayed vacations, days filled with hobbies, and more time with family. The spreadsheets are clean, the math looks solid, and your financial advisor may tell you something reassuring like: “Spending typically declines with age.” This is, in part, true.

But like most comforting generalizations, it hides a much messier reality. In fact, your retirement expenses are not a smooth downward slope. They’re more like a two-act play: Act One features fun and freedom, and Act Two, if you’re lucky enough to live long enough, brings a dramatic plot twist—one involving health issues, long-term care, and a rapidly shrinking nest egg.

To build a retirement strategy that actually holds up under pressure, you need to understand two contrasting trends:

- General retirement planners model a gradual decline in spending as you age.

- Long-term care planners model a sharp increase in costs late in life.

- Reality contains both.

In other words, your retirement plan needs to anticipate two financial phases:

- Phase One: Declining discretionary spending (fun stuff).

- Phase Two: Increasing non-discretionary care costs (necessary and often costly).

Let’s unpack this and see what you should be doing now to prepare.

Phase One: The “Go-Go” Years and the Myth of Declining Spending

Retirement planners often reference what’s affectionately known as the “go-go years” — typically the first decade or so after retirement. During this period, retirees tend to spend more freely on travel, dining, hobbies, grandchildren, and other forms of discretionary joy. This is when the “every day is Saturday” vibe is strongest.

After this initial burst of activity, spending tends to slow down naturally:

- People become less mobile.

- Big-ticket travel loses its appeal.

- Hobbies and events give way to quieter routines.

This trend is real and often supported by consumer data. Households led by someone aged 75 or older spend, on average, about 20% less than those in their mid-60s. For this reason, many advisors model retirement spending as gradually decreasing — a neat, downward-sloping line on your Excel chart.

But here’s the twist: that line doesn’t tell the whole story.

Phase Two: The “No-Go” Years and the Long-Term Care Explosion

While general spending on fun may taper off, healthcare and long-term care costs can—and often do—skyrocket.

Here’s the stark truth:

- By age 80, the odds of needing help with activities of daily living (ADLs)—things like bathing, dressing, using the toilet, eating, and mobility—grow substantially.

- The U.S. Census Bureau expects the number of Americans over 85 to nearly double by 2035, and nearly triple by 2060.

- A recent CareScout study found that the monthly median cost of a private nursing home room in 2024 was $10,646. That’s not a typo.

- Costs for assisted living, homemaker services, and nursing home care all jumped around 10% in 2024 alone, well above the general inflation rate.

And here’s the kicker: Medicare does not cover long-term care beyond short-term rehab following hospitalization. Nearly half of Americans age 65 or older incorrectly believe it does. This misunderstanding leaves many retirees dangerously unprepared.

Your Real Retirement Has a Split Personality

You’re not planning for one retirement — you’re planning for two very different financial periods:

- Phase One: Early Retirement

- Focus: Discretionary spending

- Strategy: Flexible withdrawals, optimizing investment returns, and enjoying life

- Risk: Overspending too early or overestimating portfolio longevity

- Phase Two: Late Retirement

- Focus: Health care, long-term care, and essential living expenses

- Strategy: Protecting assets, planning for guaranteed income, and managing care needs

- Risk: Underestimating care needs and running out of money

Too many retirement plans model only Phase One and cross their fingers for Phase Two. This is why retirees often end up re-entering the workforce in their 70s, selling off assets in a panic, or becoming reliant on family members who are also financially strained.

So What Should You Actually Do?

Let’s get practical. Here’s how to build a retirement plan that can flex for both phases:

1.

Segment Your Spending Strategy

Break your retirement budget into three categories:

- Essential needs (housing, food, health insurance)

- Discretionary wants (travel, hobbies, entertainment)

- Potential care costs (assisted living, home care, nursing facilities)