Beyond the Bone: How Feathers and Physics Rewrote History

Gemini:

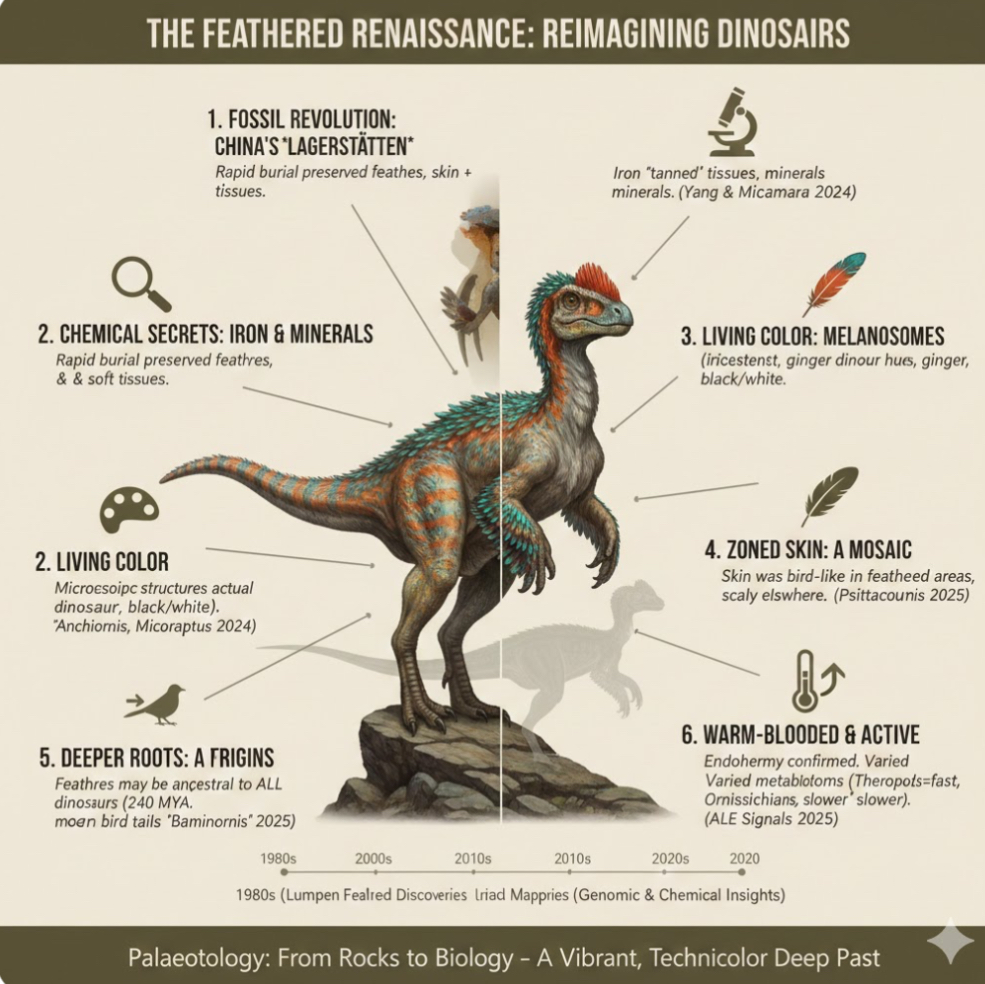

The Feathered Renaissance: How Palaeontology Reimagined the Deep Past

For most of the 20th century, the “dinosaur” lived in the popular imagination as a biological failure. In films and textbooks, they were depicted as “lumpen lizards”—sluggish, scaly, cold-blooded monsters that dragged their tails through primeval swamps, eventually stumbling into an evolutionary dead end. However, the last four decades have seen a scientific revolution so profound that it has effectively “resurrected” these creatures, transforming them from clumsy reptiles into the vibrant, active, and feathered ancestors of modern birds.

This transformation is not just a change in artistic style; it is a shift in our fundamental understanding of how life on Earth evolves. It is the story of how new fossils, high-tech chemistry, and a “dinosaur renaissance” rewrote the history of the world.

The Great Reveal: The Jehol Biota

The turning point began in the late 1990s, when a window into the deep past opened in northeastern China. In the province of Liaoning, volcanic eruptions 130 million years ago had acted as a “Mesozoic Pompeii,” burying entire ecosystems in fine ash and lake mud. These sites, known as the Jehol Biota, produced something the world had never seen: non-avian dinosaurs preserved with feathers.1

Sites like these are known as Lagerstätten—fossil sites with extraordinary preservation. Unlike typical fossils, where only bones remain, these specimens captured the “soft” side of life.2 We saw the “dino-fuzz” on the small predator Sinosauropteryx and the long, quill-like feathers on the arms of Velociraptors. Suddenly, the “lumpen lizard” was gone, replaced by creatures that looked more like hawks or roadrunners than crocodiles.

The Chemistry of the “Scientific Miracle”

How did delicate feathers survive for 100 million years? For a long time, it was assumed that soft tissue simply vanished over time.3 Modern palaeontology has discovered that preservation is a complex chemical trap.

When these dinosaurs were buried rapidly in oxygen-free mud, a unique process began. Iron from the animal’s own blood acted like a natural embalming fluid, “tanning” the proteins in the skin and feathers into a stable form. Meanwhile, minerals like silica or phosphate seeped into the cells, essentially “shrink-wrapping” the biological structures at a molecular level. Recent 2024 research led by Dr. Zixiao Yang and Prof. Maria McNamara even revealed that some fossils are preserved in silica—the same material as glass—allowing scientists to see individual skin cells under a microscope.4

Living Color: The Microscopic Detectives

Perhaps the most “science-fiction” development in recent years is our ability to determine the actual colors of dinosaurs. Scientists discovered that feathers contain melanosomes—tiny packets of pigment.5 Crucially, the shape of these packets dictates the color: sausage-like shapes for black, spherical ones for ginger-red, and flat, platelet-like shapes for iridescence.

By mapping these shapes across fossils like Anchiornis, researchers have reconstructed them with “mohawk” crests and spangled wings. We now know that dinosaur color wasn’t just for camouflage; it was used for social signaling, sexual display, and perhaps even temperature regulation. This has shifted the study of dinosaurs from geology (looking at rocks) to biology (looking at living systems).

The Latest Frontier: Zoned Skin and the Triassic Mystery

As we move into 2025, the pace of discovery has only accelerated. We are now realizing that the transition from a scaly reptile to a feathered bird was far “messier” than we thought.

Research published in 2024 identified “zoned development” in dinosaur skin.6 A study of Psittacosaurusshowed that these animals had “bird-like” skin only where they had feathers, while the rest of their body remained scaly like a modern crocodile.7 This suggests that the evolutionary “kit” for becoming a bird was assembled piece-by-piece, with different parts of the body evolving at different rates.8

Furthermore, the timeline is being pushed back. In early 2025, the discovery of Baminornis zhenghensis in China revealed a bird with a modern, short tail (a pygostyle) living 150 million years ago—nearly 20 million years earlier than previously recorded.9 Even more startling is the Triassic Origin Hypothesis. 2025 studies on Triassic reptiles like Mirasaura suggest that feather-like structures might have evolved 240 million years ago, long before the first “true” dinosaurs even appeared.

A New Vision of the Past

Today, palaeontology is a high-tech discipline. We use particle accelerators (synchrotrons) to detect “ghosts” of pigments and CT scans to reconstruct dinosaur brains. We have learned that the “great extinction” 66 million years ago wasn’t the end of the story—one branch of the dinosaur family tree simply took to the skies.

When you look at a sparrow in your garden, you aren’t looking at a “distant relative” of a dinosaur; you are looking at a living dinosaur. In the last forty years, we have stopped seeing dinosaurs as symbols of failure and started seeing them for what they truly were: one of the most successful, colorful, and resilient experiments in the history of life.

The journey to “see” the colors of the past has been one of the most exciting sagas in modern science. Below is a timeline of the most significant breakthroughs that allowed palaeontologists to move from monochromatic bones to a vibrant, technicolor Mesozoic.

Timeline: The “Color-Mapping” Revolution

2010: The “Big Bang” of Paleo-color

Two landmark papers published within weeks of each other changed everything.

• The Subject: Sinosauropteryx.

• The Discovery: Researchers identified spherical melanosomes in the tail feathers, proving it had ginger-colored stripes and a reddish-brown body.

• The Subject: Anchiornis.

• The Discovery: This was the first dinosaur to have its entire body color-mapped. It revealed a grey body, white-and-black spangled wings, and a striking red crown.

2012: The Discovery of Iridescence

• The Subject: Microraptor.

• The Discovery: By finding long, flat, platelet-shaped melanosomes, scientists realized this four-winged predator didn’t just have black feathers—it had a glossy, iridescent sheen, much like a modern crow or grackle. This suggested it was likely active during the day, as iridescence is a visual signal used in sunlight.

2016: Decoding Camouflage Strategies

• The Subject: Psittacosaurus.

• The Discovery: Instead of feathers, scientists studied the skin of this “parrot-lizard.” They found countershading—dark on the back and light on the belly.

• The Significance: By building a 3D model and testing it under different lighting, they proved this specific pattern was a form of forest camouflage, helping the animal disappear into the shadows of a leafy canopy.

2018: The Rainbow Dinosaur

• The Subject: Caihong juji (Mandarin for “Rainbow with a Big Crest”).

• The Discovery: This Jurassic dinosaur possessed specialized melanosomes in its neck feathers that are identical to those in modern hummingbirds. It is the earliest evidence of a “rainbow” iridescent display used for attracting mates.

2024: The “Zoned Skin” Revelation

• The Subject: High-resolution analysis of Psittacosaurus skin.

• The Discovery: This study showed that color and texture were “zoned.” The animal had bird-like skin(thin and flexible) in feathered areas to support movement, but reptile-like scales (thick and pigmented) in others.

• The Significance: It proved that the transition from scales to feathers involved a complete microscopic redesign of the skin itself, not just the appearance of fluff.

2025: The Jurassic Modern-Tail

• The Subject: Baminornis zhenghensis.

• The Discovery: While not just about color, this discovery pushed back the appearance of a modern-style tail (the pygostyle) to 150 million years ago.

• The Significance: It suggests that the “canvas” for color displays—the fan-shaped tail we see in peacocks or turkeys—was already functionally available to dinosaurs in the Jurassic, much earlier than once thought.

Summary of Pigment Discovery

Year Dinosaur Primary Color/Pattern Significance

2010 Sinosauropteryx Ginger stripes First proof of color.

2010 Anchiornis Black, White, Red First full-body map.

2012 Microraptor Iridescent Black First proof of “shiny” feathers.

2018 Caihong Rainbow Iridescence Earliest hummingbird-like display.

2024 Psittacosaurus Countershaded Proved forest-dwelling behavior.

2,000-Year-Old Superhighways

ChatGPT:

Roman Roads: The Ancient Superhighways That Refused to Disappear

If you’ve ever walked along a strangely straight country lane in Europe, there’s a good chance you were following a ghost from the ancient world. The Roman road system didn’t just move soldiers and merchants — it stitched together an empire. And remarkably, parts of it are still doing the job today.

The Romans didn’t invent roads. But they turned road-building into a statecraft — blending engineering discipline, imperial ambition, and long-term thinking in a way the world had never seen before.

How to Build a Road That Lasts 2,000 Years

Roman engineers approached road-building with a simple principle: control the water, control the future. Before a shovel hit the ground, surveyors laid out carefully-chosen routes with straight alignments, ridge-top corridors, and practical river crossings. Then the real work began.

First came a trench along the planned route. Into this went multiple engineered layers:

• a base of large stones to spread weight

• a compacted layer of gravel and lime mortar

• a fine bedding layer

• and finally, stone paving — basalt near volcanoes, limestone elsewhere

The finished roadbed was raised and gently curved, so rainwater ran off the surface rather than soaking in. Deep roadside ditches and embankments carried runoff further away.

It wasn’t glamorous work. Soldiers, slaves, and laborers crushed gravel, hauled stone, and rammed soil day after day. But the result was a structure built from the ground up for durability and drainage — not for comfort. When traffic rolled over these roads, the metal-rimmed wheels actually helped compress the layers tighter. The more the roads were used, the stronger they became.

That’s why some Roman roads are still serviceable today. They were deliberately overbuilt, with strong foundations and legal protections that prevented people from tearing them up casually. Stability was the intention.

Mapping Roads That Are No Longer There

But here’s the historian’s challenge: most Roman roads are not still visible. Many lie beneath modern highways, farm fields, or cities. So how do we know where they once ran?

The answer is detective work.

Archaeologists look for clues like stone remains, milestones, and ancient travel manuals that list distances between stations. Aerial and satellite imaging reveal faint crop marks where buried stone changes how plants grow. Laser scanning exposes hidden embankments beneath forests. And modern mapping models simulate how a Roman engineer would have chosen the most efficient route across a landscape.

Recently, a digital project called Itiner-e combined these approaches and concluded that the Roman network likely reached 187,000 miles — far more than earlier estimates. Only a tiny percentage of routes are confirmed precisely, but the picture is clear: this was the most integrated road system the world had seen.

How Roads Move Ideas — Not Just People

Roman roads weren’t just slabs of stone. They were cultural highways.

Troops marched quickly to troubled frontiers. Merchants moved goods inland. Pilgrims traveled to holy sites. Early Christian communities — including missionaries like the apostle Paul — used these routes to spread their message. Even epidemics followed the same paths: historians now link the spread of the Antonine Plague to the efficiency of Roman mobility.

Roads, in other words, were the internet of the ancient world. They connected people, accelerated exchange, and shrank distance.

What Happened When Modern Technology Arrived?

For a long time after Rome fell, much of Europe continued to travel along Roman alignments.

Then the industrial age happened.

Railways and later highways reshaped how goods and people moved. Modern designers often rediscovered that Roman engineers had already picked the best routes — so they paved right over them. Other times, modern planners chose different corridors and Roman roads disappeared beneath farms.

But the idea that infrastructure could bind a civilization together never went away. The Roman lesson — that transport equals power — still shapes our world.

How Rome Compared With China and Persia

Rome wasn’t the only civilization to take transportation seriously. Comparing it to Persia and China shows three different philosophies.

The Persian Achaemenid Empire (6th–4th century BCE) built the famous Royal Road — a 1,600-mile communication artery from Turkey to Iran. It featured bridges, guarded way-stations, and courier relays so fast that messages crossed continents in a week. But Persian roads were mainly graded earth and gravel, built for horses and caravans rather than heavy wagons. They prioritized speed of information, not long-term pavement.

Ancient China, especially during the Qin and Han dynasties, built an internal road grid to unify a massive territory. Roads were often made of rammed earth, brick, or gravel — durable but not stone-set like Rome’s highways. China also paired roads with canal systems, making water transport central to freight movement. Where Rome built infrastructure outward toward new provinces, China built it inward to strengthen the state core.

Rome’s distinction is that it designed roads to carry long-term wheeled traffic across rugged terrain, often in straight, disciplined alignments, with heavy stone foundations that defied erosion and time.

In short:

• Persia excelled at communication

• China excelled at state-planned integration

• Rome excelled at durable engineering

Different empires — different needs — different solutions.

Why Roman Roads Still Matter

Roman roads endure for the simplest reason: they were built to outlast the people who made them.

They remind us that infrastructure is never neutral. It shapes how societies live, think, trade, govern, and believe. Whether it’s a stone road in Judea, a canal in China, or a fiber-optic cable on the ocean floor, the same truth applies:

Whoever builds the connections, shapes the world.

And sometimes, they shape it for two thousand years.

Beneath the Surface, Beyond the Signal: The Quantum Revolution in Navigation

ChatGPT:

Navigating Without GPS: How Quantum Inertial Navigation Systems Are Changing the Game

By someone who doesn’t need Google Maps to tell them where they are (because they use atoms)

⸻

Imagine you’re deep underground on a train in the London Underground. No windows. No sunlight. No signal. Your phone can’t tell you where you are, and GPS? Forget it. You’re in a concrete tunnel hurtling through darkness. But the train still knows exactly where it is. Not because it has a map, and not because of some guy up front with a compass and good vibes — but because it’s carrying a box of freezing cold atoms and lasers that whisper quantum secrets.

Welcome to the world of quantum inertial navigation systems — the technology that could let us travel, explore, and monitor places where GPS signals can’t reach. Underground, underwater, even in space.

⸻

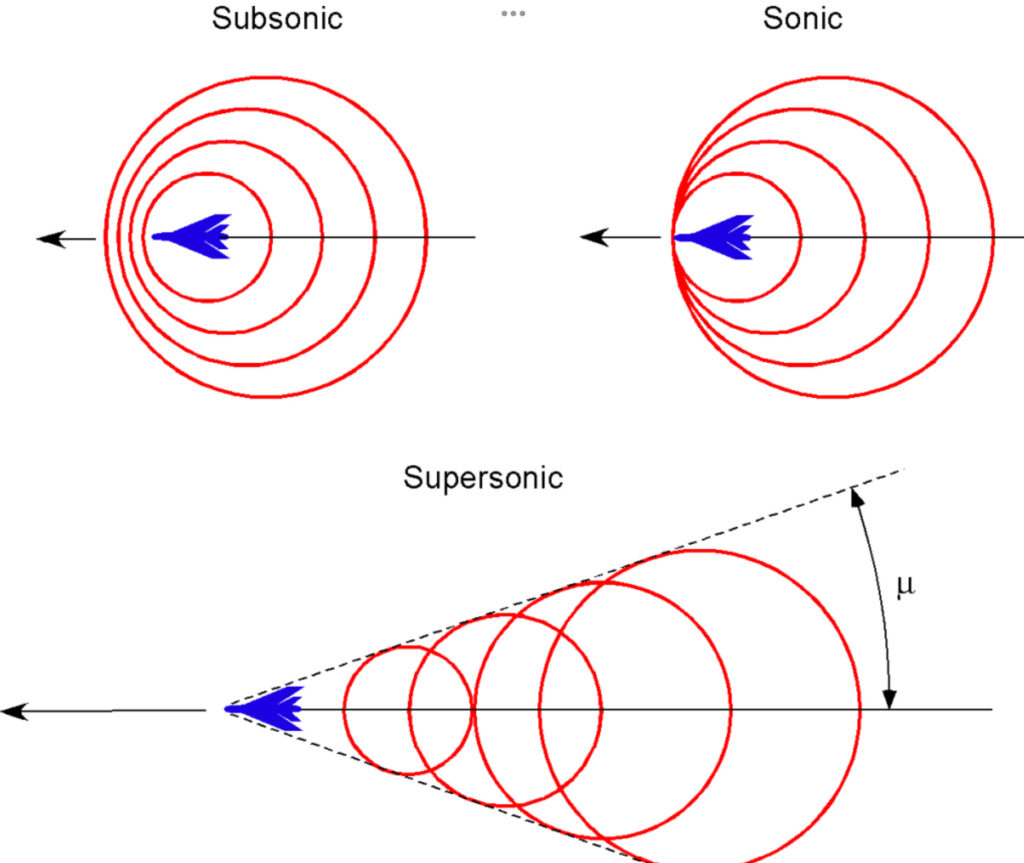

Why We Need Something Better Than GPS

Most navigation systems today rely heavily on GPS, which uses signals from satellites to triangulate your position. Great in open areas, but try using it:

• Inside a subway tunnel

• Beneath the ocean

• On a long-haul plane crossing the polar regions

In those situations, GPS signals are blocked, bounced, or just not available. That’s where inertial navigation systems (INS) come in. These systems use motion sensors — accelerometers and gyroscopes — to track how far you’ve moved from a known position.

These are the same sensors in your phone that tell it when you’ve rotated the screen. They’re also in planes, missiles, and self-driving cars. But here’s the catch: they drift. They don’t know where they are — they guess based on movement. And that guess gets worse the longer they go without GPS to reset them.

Give a classical inertial navigation system 10 minutes with no external reference, and it’ll think you’ve traveled 30 meters when you’ve barely moved. It’s like trying to navigate a city blindfolded while counting your steps and hoping you don’t fall into a fountain.

⸻

Enter: Quantum Inertial Navigation

Quantum inertial navigation systems (QINS) aim to fix this — using quantum physics instead of springs, gears, and error-prone math.

At the heart of QINS is a technique called atom interferometry. Sounds intense, and it is, but the concept is surprisingly elegant:

1. Cool atoms (like rubidium) to near absolute zero using lasers — yes, lasers can cool things. At these ultra-cold temperatures, atoms slow down and behave like waves instead of little balls.

2. Use lasers to split the atom wave into two separate paths — like sending it on two journeys at once.

3. Let those two parts of the atom wave travel slightly different paths, then recombine them.

4. The result is an interference pattern, like ripples on a pond overlapping. The pattern changes based on how the atom moved during its journey.

By analyzing that pattern, scientists can tell how the atom — and therefore the system it’s riding in — has moved: whether it accelerated, turned, tilted, or wobbled. It’s motion tracking based on the fundamental behavior of matter itself.

And because the measurement comes from quantum effects, it doesn’t drift like classical systems do. You can go longer without resetting your position and still get accurate navigation.

⸻

But Wait — How Does It Work on a Shaky Train?

You’re probably thinking, “If these atoms are so sensitive, how do they work on a train that’s literally vibrating, shaking, and occasionally doing interpretive dance on old tracks?”

Good point. That’s where noise cancellation comes in. Engineers build vibration isolation platforms — kind of like floating shock absorbers — to protect the quantum system from unnecessary shaking. They also use reference sensors to detect and subtract environmental noise, so only the useful motion signals remain.

And here’s the cool part: the system doesn’t just ignore motion from the train — it uses it. If the train hits a bump, or leans slightly on a turn, the quantum system picks that up. Engineers can then use that data to detect:

• Track wear

• Structural issues

• Changes in vibration patterns

In other words, your train becomes a mobile diagnostic lab, detecting potential problems before something breaks.

In short: classical IMUs are fast and cheap, but not reliable over time. Quantum systems are slow and expensive, but insanely precise. The ideal setup? Use both. Let the classical system handle quick changes, and let the quantum system provide the ground truth to keep it honest.

What’s Next?

Right now, quantum inertial navigation systems are still being refined. They’re bulky, expensive, and not quite ready to fit in your smartphone — unless your phone has a vacuum chamber and a cryogenic cooling unit. But researchers are working hard to make them smaller and cheaper.

The goal? A GPS-free navigation system that works anywhere:

- Inside mines

- Deep in the ocean

- Across planets

- Or even on a future moon base

It’s like giving explorers a sixth sense — a way to know where they are based on the laws of physics, not the kindness of satellites.

Final Thought

The next time you check your location on your phone, remember: it’s a fragile miracle. And the future of navigation may not come from space, but from the tiniest particles on Earth — atoms cooled to near nothingness, measuring motion with quantum accuracy.

It’s a strange, beautiful, sci-fi idea that just happens to be real — and it’s riding the train with you.

The Neuroscience of Aging: Why Efficiency Weakens the Mind

ChatGPT:

🧠 Aging Well by Keeping the Mind Open

Why Walking, Art, and Curiosity Matter More Than Efficient Learning

As we age, many people worry that their brains are “slowing down” or losing sharpness. Yet modern neuroscience offers a more nuanced picture. The aging brain is not simply declining — it is rebalancing how it makes decisions and interprets the world. Understanding this shift helps explain why certain everyday activities support healthy aging, while others, surprisingly, do not.

The aging brain is not failing — it is recalibrating

Over a lifetime, the brain accumulates experience. Patterns repeat, lessons are learned, and internal expectations about how the world works become stronger. At the same time, sensory input — sight, hearing, speed — may become slightly noisier. From the perspective of Bayesian brain theory, this is not a defect but a sensible adaptation: when incoming information is less precise, the brain leans more on what it already knows.

The challenge of aging, then, is not simply memory loss. It is keeping experience flexible rather than rigid — allowing beliefs to update when needed instead of hardening into certainty.

Why thinking alone while walking supports the aging mind

Walking creates an almost ideal cognitive environment for this kind of flexibility.

When we walk, especially alone, the brain receives steady, reliable sensory input: movement, balance, changing scenery. At the same time, there is no demand to reach conclusions, explain ourselves, or perform socially. Thought unfolds without pressure.

Unlike sitting still and “trying to think,” walking distributes cognition across body and brain. Mental loops soften. Ideas drift, overlap, and return. Old assumptions are not attacked or defended — they are quietly reorganized. This is why insights during walks often feel as if they arrive on their own. The brain is updating gently, without force.

Why art and music work differently from ordinary information

Art and music support the aging brain in a way that explanations and instructions cannot.

They provide rich sensory experience without telling us what it means. Music unfolds in time and cannot be skimmed. Art allows ambiguity, multiple interpretations, and emotional response without demanding verbal clarity. There is no single “correct” understanding to reach.

For older adults, this matters deeply. Strong experience-based beliefs remain intact, but they stay flexible. Emotion engages learning without pressure. This is why art can feel unexpectedly moving, even tear-inducing: such moments often signal internal recalibration rather than nostalgia.

Museums as cognitive ecosystems — when used gently

Museums combine many of these beneficial conditions: slow movement, quiet spaces, and permission to linger. But these benefits disappear when museums are treated as tasks to complete or lessons to master.

A museum visit that supports cognitive health:

- Enters without a goal to “learn something”

- Walks first, stops later

- Lingers when something interrupts emotionally

- Delays labels and explanations

- Leaves before feeling saturated

In this mode, the museum becomes a space for internal reorganization rather than information intake. Meaning emerges later, often during a quiet walk afterward.

Why guided tours often feel exhausting

Guided tours are tiring not because they are boring, but because they work against the brain’s natural updating process.

They impose continuous verbal explanation, a single authoritative interpretation, and sustained attentional demand. Social pressure adds another layer: keeping up, following along, appearing engaged. Silence and recovery are rare.

For aging brains, this combination is costly. Sensory richness is low, cognitive load is high, and personal pacing disappears. Even excellent guides can unintentionally shut down curiosity and internal dialogue. The fatigue people feel afterward is not disinterest — it is the brain seeking recovery.

Why not all learning strengthens the aging brain

This is where summaries enter the picture.

Summaries are designed to be efficient. They compress complexity, reduce uncertainty, and deliver conclusions quickly. They feel satisfying because they provide closure and a sense of mastery.

But cognitively, summaries function much like guided tours. They confirm existing beliefs instead of reshaping them. For aging brains already inclined to rely on experience, summaries tilt the balance too far toward certainty. Learning becomes recognition rather than revision.

In other words, summaries often strengthen confidence without strengthening flexibility — and flexibility is what aging cognition needs most.

Why curiosity, not efficiency, protects the aging mind

Memory drills, speed exercises, and constant explanations train performance. Curiosity trains something deeper.

Curiosity keeps questions alive. It tolerates uncertainty. It invites exploration without urgency or pressure. It preserves multiple possible interpretations instead of collapsing them into one.

For the aging brain, the goal is not speed or volume of information, but calibration — knowing how confident to be, when to revise beliefs, and when to remain open.

Final takeaway

The aging brain thrives when experience remains open to revision.

Activities like walking alone, listening to music, looking at art, and wandering museums slowly all share a crucial feature: they provide rich input without forcing conclusions. Guided tours, summaries, and constant explanation feel efficient, but they quietly undermine the flexibility that aging minds depend on.

To age well cognitively is not to know more — it is to keep knowing changeable.

Aging Smart: The Essential Guide to Later Life

ChatGPT:

📘 The Later Years: A Practical Guide to Ageing with Confidence

As people grow older, life often becomes more complicated — not just physically or emotionally, but administratively. There are legal documents to manage, finances to organize, medical preferences to articulate, and essential decisions to be made. Yet many people delay or avoid these crucial steps, often leaving their loved ones to deal with uncertainty and stress later on.

Sir Peter Thornton KC — a former Chief Coroner of England and Wales — tackles this reality head-on in The Later Years, an accessible and invaluable guide for navigating the often-overwhelming practicalities of growing older. Drawing on his extensive legal background, Thornton offers a book not of reflection or philosophical musing, but of actionable guidance, organized in checklists and clearly structured sections.

Whether you’re approaching retirement, caring for aging parents, or simply planning ahead, The Later Years is a must-read roadmap to aging wisely, securely, and with dignity.

⸻

🧭 What Is This Book About?

At its heart, The Later Years is a comprehensive toolkit for managing the key aspects of later life. It’s a book about preparing — legally, financially, and emotionally — for the transitions that come with aging. Thornton’s aim is to reduce the uncertainty and fear many feel around aging by providing clear, practical steps for each stage of later life.

He emphasizes not only what to do, but how to do it, and — crucially — when to start. The tone is straightforward, never patronizing, and assumes that readers want to retain control of their lives and reduce the burden on others.

⸻

📌 Key Topics Covered

The book is structured into several thematic sections that mirror the natural progression of later life and the challenges it brings.

1. Legal Preparation Before Death

One of the central concerns Thornton addresses is the need to get your affairs in order. This includes writing or updating a will, setting up a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) for health and finance, and drafting an advance statement to communicate medical and personal preferences.

He emphasizes how these documents protect both the individual and their loved ones — avoiding confusion, conflict, and legal complications down the line.

2. Managing Money in Later Life

Thornton offers robust advice on financial matters — from protecting against scams to understanding pensions, savings, and benefits. He covers how to manage borrowing, access pension credits, and handle investment pitfalls, particularly those that often target older adults.

3. Avoiding Fraud and Exploitation

A standout section of the book discusses how to recognize and avoid scams. Thornton walks readers through common fraud tactics — such as impersonation scams, phishing emails, or fake bank calls — and provides easy-to-follow checklists for staying safe. His legal insight brings unique authority to this chapter, making it one of the most practically valuable parts of the book.

4. Health, Care, and Living Choices

As people age, medical decisions and living arrangements take center stage. Thornton provides a realistic look at care homes, NHS systems, and home-based care, including how to make informed choices and what your rights are as a patient and resident.

5. Rights and Dignity

One of the book’s most empowering sections is the “Charter of Rights” — a reminder that older people are not powerless. It outlines legal protections against discrimination and abuse and highlights entitlements in areas like housing, care, and decision-making.

6. What Happens After a Death

In a particularly sensitive but vital section, Thornton addresses the practical steps families must take after a loved one passes. This includes registering a death, managing estate matters, and claiming or stopping pensions. He delivers this with clarity, empathy, and precision, helping families avoid unnecessary confusion during a difficult time.

⸻

🧠 What Makes This Book Unique?

Where other books on aging may drift into theory or emotional storytelling, The Later Years is relentlessly practical. Thornton uses his legal expertise to break down bureaucratic and legal tasks into bite-sized, manageable actions. The book reads like a trusted checklist from someone who’s seen what happens when people don’t prepare — and is determined to help you avoid those mistakes.

Another strength is its non-patronizing tone. Thornton respects the autonomy and intelligence of older readers. He doesn’t speak to older adults; he speaks with them, as a partner in planning for the future.

⸻

💬 Who Should Read This Book?

The Later Years is for:

• Adults 50+ who want to prepare for their future.

• Family members or caregivers managing aging loved ones.

• Anyone looking to understand the legal and practical framework of aging in the UK.

Even younger adults will benefit, especially those who want to help their parents or understand the decisions that will eventually affect them too.

⸻

🏁 Conclusion: Taking Control of Aging

The Later Years is more than a guide — it’s a companion for a stage of life that is often ignored or misunderstood. Thornton’s core message is that with planning, aging doesn’t have to be frightening. You can control your choices, protect your family, and approach the later years with clarity and peace of mind.

Whether you’re planning for decades ahead or already facing these issues, this book gives you the tools to make your voice heard and your wishes respected.

As Thornton reminds us, aging is inevitable — but confusion and chaos don’t have to be. With the right knowledge, aging can be orderly, empowered, and even liberating.

Prediction, Experience, and Plasticity in the Aging Brain

ChatGPT:

🧠 How the Aging Brain Thinks: A Bayesian View of Wisdom, Learning, and Curiosity

1. The basic idea of Bayesian Brain Theory

Bayesian Brain Theory says the brain is not a passive recorder of reality.

Instead, it is a prediction machine:

It uses past experience to form expectations (priors)

It compares those expectations with incoming sensory information (evidence)

It updates its understanding when the mismatch (prediction error) is meaningful

Perception, judgment, and decision-making are all forms of educated guessing under uncertainty.

The brain is constantly balancing:

“What I already believe”

With “What I am sensing right now”

2. What changes with aging: stronger priors, noisier evidence

- As we age, two predictable shifts occur:

- Priors strengthen

- Decades of experience produce stable internal models

- Patterns repeat; lessons accumulate

- Sensory precision may decline

- Vision, hearing, reaction speed, and fine discrimination become noisier

- Priors strengthen

- From a Bayesian perspective, this is not failure — it is rational adaptation:

- When evidence becomes noisy, it makes sense to trust priors more

- The aging brain is not “less intelligent”:

- It is more conservative in updating

3. How this affects decision-making

- Older adults often:

- Decide more slowly

- Change their minds less frequently

- Resist sudden reversals

- Bayesian interpretation:

- The brain requires stronger evidence before revising beliefs

- This reduces:

- Overreaction

- Emotional volatility

- Susceptibility to noise

- But it can increase:

- Resistance to novelty

- Vulnerability to outdated assumptions in fast-changing environments

4. Why some older adults become

better

decision-makers

- Aging improves decisions when:

- Priors are well-calibrated

- The environment is familiar or semi-stable

- Older adults often excel at:

- Risk management

- Long-term judgment

- Emotional regulation

- Detecting what doesn’t matter

- Bayesian translation:

- Strong priors reduce false alarms

- Emotional prediction errors are dampened

- What looks like “slowness” is often precision control, not decline

5. Cognitive reserve: a Bayesian definition

- Cognitive reserve is often described vaguely as “extra capacity.”

- Bayesian Brain Theory gives it a sharper meaning:

- Cognitive reserve is the ability to keep strong priors flexible and evidence meaningful.

- High reserve brains:

- Maintain multiple internal models (ensembles)

- Can reroute around damage or noise

- Update gradually instead of freezing

- Low reserve brains:

- Collapse toward a single explanation

- Over-rely on habit

- Lose adaptability

6. Why lifelong learning matters (and what kind matters)

- Lifelong learning does not mainly protect memory.

- It protects the updating mechanism itself.

- Effective lifelong learning:

- Preserves sensory precision

- Keeps priors from narrowing too much

- Trains tolerance for ambiguity

- Passive consumption (summaries, rote facts):

- Confirms priors

- Reduces uncertainty too quickly

- Weakens reserve over time

- Active engagement:

- Strengthens Bayesian balance

- Maintains adaptability

7. Why music uniquely supports Bayesian updating

- Music is prediction without words:

- Rhythm sets expectations

- Melody violates and resolves them

- You cannot skim music.

- The brain must:

- Continuously predict

- Adjust timing expectations

- Regulate emotion

- Bayesian benefits:

- Trains dynamic prediction error handling

- Improves emotional calibration

- Preserves uncertainty tolerance

- Music is Bayesian exercise without intellectual strain.

8. Why walking is powerful for aging cognition

- Walking supplies:

- Reliable sensory input (movement, balance, visual flow)

- Low cognitive demand

- No forced conclusions

- Bayesian effects:

- Sensory precision quietly improves

- Prediction errors remain gentle and continuous

- Priors reorganize without being attacked

- Walking alone adds:

- No social pressure

- No performance demand

- No need for closure

- This creates ideal conditions for slow belief updating.

9. Why art and museums work differently from explanations

- Art provides:

- Rich sensory evidence

- Without a single correct interpretation

- Museums create:

- Silence

- Slow movement

- Permission to linger

- Bayesian impact:

- Ensembles of meaning remain open

- Priors soften and rearrange

- Updating happens below language

- This is why art can move people emotionally:

- Tears signal recalibration, not nostalgia

10. Why curiosity beats memory drills

- Memory drills train:

- Retrieval

- Speed

- Short-term performance

- But they do little for:

- Model flexibility

- Evidence weighting

- Uncertainty handling

- Curiosity does the opposite:

- Keeps questions alive

- Invites prediction errors

- Encourages exploration without pressure

- Bayesian translation:

- Curiosity keeps the posterior broad

- Memory drills narrow it

11. The deep principle tying it all together

- Aging cognition thrives not on:

- Speed

- Volume

- Information accumulation

- But on:

- Calibration

- Flexibility

- Meaningful updating

- Music, walking, art, and curiosity all:

- Preserve uncertainty

- Protect sensory engagement

- Prevent premature closure

🧭 Final takeaway

Bayesian Brain Theory shows that aging minds do not fail — they rebalance.

Cognitive reserve depends on maintaining that balance.

Lifelong learning is not about remembering more.

It is about keeping the brain capable of revising what it already knows.

And the best tools for that are not drills or summaries —

but curiosity,

movement,

music,

and art.

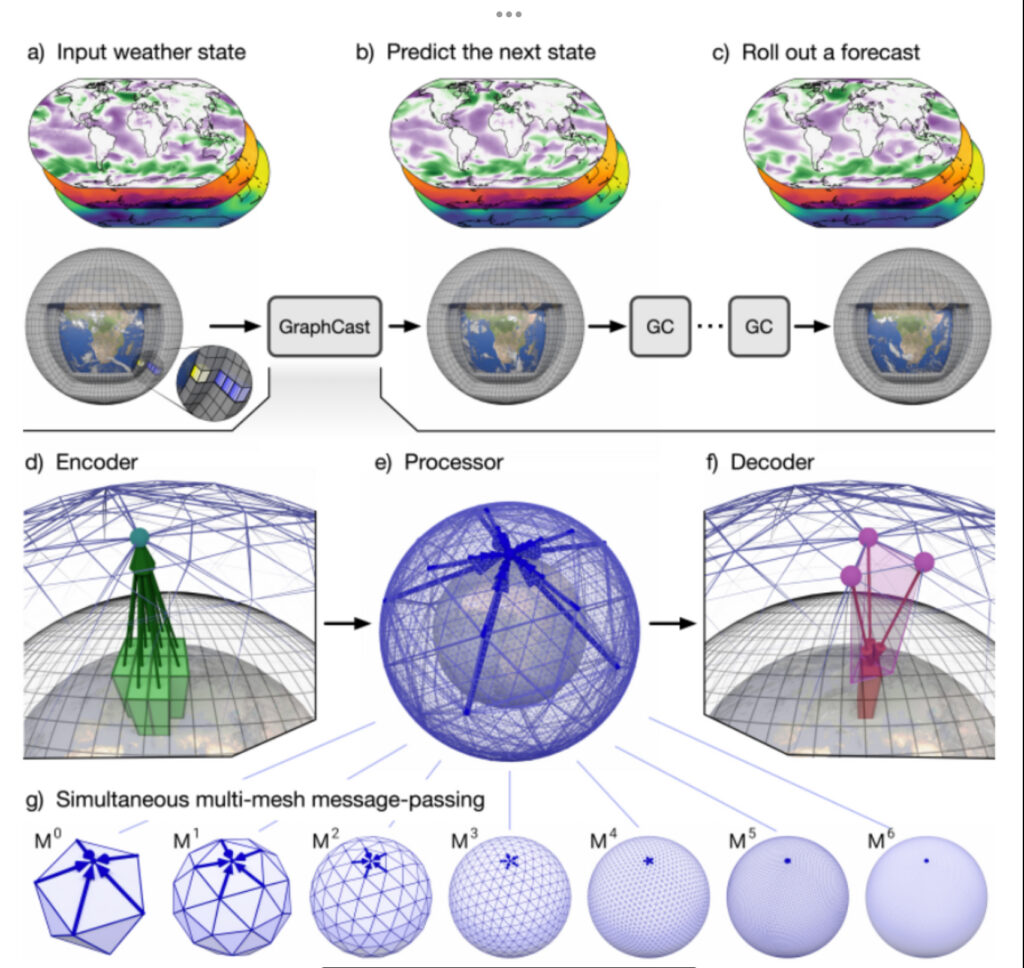

From Equations to Patterns: How We Really Predict the Weather

ChatGPT:

🌦️ Weather Forecasting Today: Why Humans, Physics, and AI All Matter

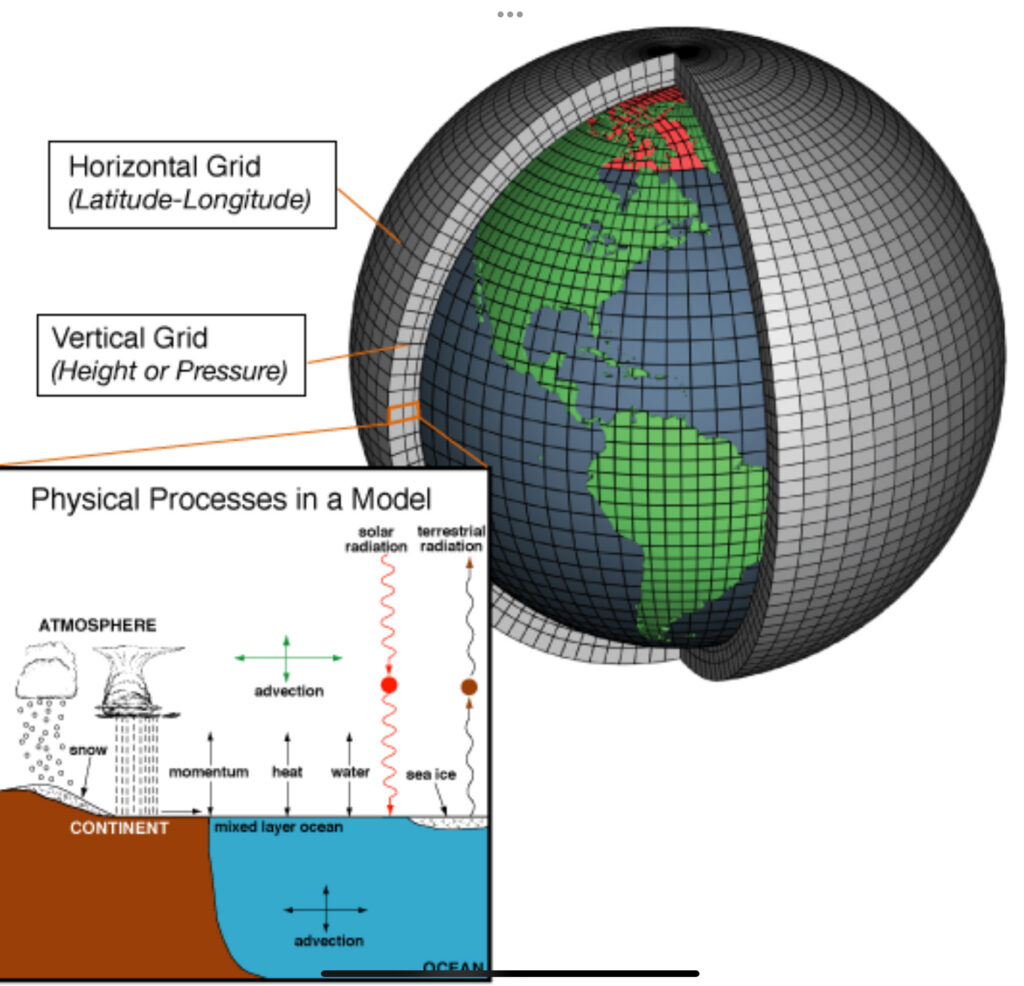

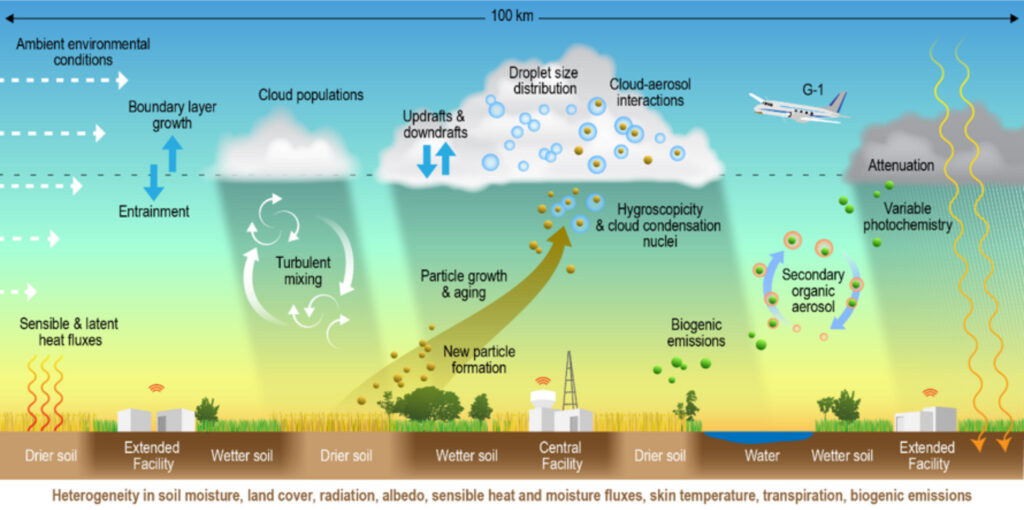

Modern weather forecasts may look simple on your phone, but behind them lies one of the most complex prediction problems humans have ever tackled. To understand why forecasts have improved so much — and why meteorologists still consult many models — we need to look at two very different forecasting philosophies: traditional computer (physics-based) models and newer AI-based methods.

⸻

1. What traditional computer forecast models actually do

• Physics-based weather models (often called numerical weather prediction models) attempt to simulate the atmosphere directly.

• They divide the Earth’s atmosphere into millions of 3-D grid boxes and calculate:

• Air movement

• Temperature changes

• Moisture, clouds, and radiation

• These calculations rely on well-known physical laws: fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, and energy balance.

• The model steps forward in time, minute by minute, computing what should happen next.

Strengths

• Firmly grounded in physical laws

• Transparent: scientists know which equations are being solved

• Can handle situations never seen before (new climates, unusual extremes)

Limits

• The atmosphere is chaotic: tiny errors in starting conditions grow rapidly

• Many crucial processes (clouds, turbulence) must be approximated

• Higher resolution means exponentially more computing power

• Even small biases can compound over days

👉 Result: physics models are powerful but never perfect.

⸻

2. Why meteorologists must consult many different models

Meteorologists often check five, ten, or even more models, not because they are uncertain, but because uncertainty is unavoidable.

• No model starts with perfect data

• Observations are incomplete and noisy

• Different models make different compromises

• Resolution

• Cloud treatment

• Ocean-atmosphere coupling

• Some models are better for certain situations

• Heat waves

• Winter storms

• Tropical systems

• Local fog or thunderstorms

Instead of asking:

“Which model is right?”

Meteorologists ask:

“What range of futures is plausible?”

This multi-model approach:

• Reveals agreement (higher confidence)

• Exposes divergence (greater uncertainty)

• Helps identify outliers that may signal risk

⸻

3. Ensemble forecasting: thinking in probabilities, not certainties

• Modern forecasting is probabilistic, not deterministic.

• Each model (or each run of a model) represents one possible future.

• Meteorologists examine:

• How tightly forecasts cluster

• How widely they spread

• Whether there are multiple competing outcomes

This is why forecasts often say:

• “High chance of rain”

• “Uncertainty increases after day five”

• “Small shifts could change impacts”

👉 Disagreement between models is not failure — it is information.

4. What AI weather models do differently

AI-based weather models take a fundamentally different approach.

- Instead of solving physical equations step by step, AI models:

- Learn from decades of historical weather data

- Learn how atmospheric states usually evolve

- Detect patterns across many variables at once

In simple terms:

- Physics models try to calculate the future

- AI models try to recognize the future

AI excels because it can:

- Capture complex, nonlinear relationships humans never explicitly programmed

- Learn where traditional models tend to be biased

- Produce forecasts extremely fast once trained

5. Why AI models often perform better

AI models have surprised scientists by outperforming traditional models in many forecasting tasks. Reasons include:

- Pattern detection beyond human intuition

- AI finds subtle relationships across scales

- Implicit error correction

- It learns from decades of past forecast mistakes

- No need to explicitly model every process

- Effective behavior matters more than perfect explanation

- High resolution without massive computing cost

- Fine details are learned, not calculated explicitly

The trade-off:

- AI predictions are often more accurate

- But much less interpretable

- Scientists may know that it works, but not fully why

6. Why AI does not replace traditional models

Despite their power, AI models are not used alone.

- AI may struggle in rare or unprecedented situations

- AI does not enforce physical laws by itself

- AI can be confidently wrong without warning

Therefore, meteorologists cross-check:

- AI forecasts

- Physics-based forecasts

- Ensemble behavior

Agreement across different model philosophies builds trust.

7. How meteorologists mentally “weigh” models

Meteorologists do not simply average outputs. They apply trained judgment.

- Consensus first

- When many models agree, confidence increases

- Situational expertise

- Certain models get more weight in certain weather patterns

- Bias awareness

- Forecasters know which models run too warm, too wet, or too slow

- Physical plausibility

- Forecasts that violate atmospheric logic are downgraded

- Risk sensitivity

- For floods, forecasters may emphasize wetter scenarios

- For aviation, worst-case ceilings matter most

The weighting happens mentally, based on experience — not rigid formulas.

8. Why humans remain essential

Even with AI, weather forecasting is not automated truth delivery.

- Forecasts affect:

- Safety

- Agriculture

- Transportation

- Emergency planning

- Humans interpret uncertainty and communicate risk

- Humans decide how confident to be, not just what will happen

Meteorologists act as ensemble interpreters, turning many imperfect futures into usable guidance.

🌍 Final takeaway

- Traditional models explain the atmosphere through physics.

- AI models learn how the atmosphere usually behaves.

- Meteorologists consult many models because the atmosphere is chaotic.

- AI performs better by detecting patterns humans cannot formalize.

- Human forecasters remain vital because judgment, context, and risk matter.

Modern weather forecasting is not about finding one perfect model — it is about wisely interpreting many imperfect ones.

Modern Life, Ancient Roots

ChatGPT:

It’s All Greek to Me: How Ancient Greece Shapes Modern Life

Introduction

Charlotte Higgins’ It’s All Greek to Me is a sharp and entertaining cultural analysis that explores how deeply Western civilization is rooted in ancient Greek thought, language, and tradition. With wit and clarity, Higgins explains how the stories, philosophies, and inventions of the Greeks continue to resonate in our lives—from politics and theater to psychology and sports.

Greek Mythology in Everyday Life

Greek mythology is far from dead—it’s alive in the phrases we use, the stories we tell, and even the way we think about ourselves. Higgins reveals how metaphors like “Pandora’s box,” “Achilles’ heel,” and “Trojan horse” are more than quaint idioms; they are ancient wisdom encoded into modern speech. These myths often reflect timeless human dilemmas: pride, temptation, destiny, and revenge.

The Theater of Democracy

The Greeks invented theater as both art and public discourse. Through playwrights like Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes, they created drama that reflected and questioned the values of their society. Tragedy, comedy, hubris, and catharsis all have their origins in Athenian performance, designed not just to entertain but to educate and provoke thought.

At the same time, the democratic structure of Athens allowed its citizens—free men—to participate directly in law-making and debate. Higgins explains how oratory and rhetoric developed as essential civic skills, laying the groundwork for political speech and campaign strategies used today.

Philosophical Foundations

Philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle asked questions still debated today: What is justice? What is the good life? What can we know? Their methods—especially Socratic questioning and Aristotelian logic—have shaped the disciplines of philosophy, ethics, and science. Higgins makes these ideas accessible, showing their enduring relevance in modern education and decision-making.

Gods with Human Faces

Unlike distant deities of other traditions, Greek gods were emotional, fallible, and often petty. They served as reflections of human nature rather than divine ideals. Higgins shows how these stories offered early insights into psychology, forming archetypes and narratives that influence literature, religion, and psychotherapy.

From the Marathon to the Olympics

The story of Pheidippides running from Marathon to Athens after a battle inspired not just the modern marathon, but the ideal of heroic endurance. Higgins explores how physical excellence and competition were central to Greek identity, and how these ideas echo in the modern Olympic movement and sports culture.

Greek Language and Thought

English speakers unknowingly speak Greek every day. Words like “democracy,” “philosophy,” “biology,” and “theatre” have Greek origins. Higgins explains how this linguistic legacy permeates medicine, politics, and the arts, providing not just words but entire frameworks of understanding.

Education and Elitism

In Britain, knowledge of ancient Greek was once the hallmark of the educated elite. Mastery of Greek texts, especially Homer, was essential in public schools and universities like Oxford and Cambridge. Higgins critiques this tradition, arguing that while it created cultural gatekeeping, it also embedded Greek values in British identity and governance.

Modern Echoes of Ancient Thought

From political rhetoric to superhero narratives, from philosophical ethics to the very structure of Western education, the influence of the Greeks remains. Higgins suggests that understanding their culture helps us understand ourselves—our institutions, our conflicts, and our aspirations.

Conclusion

It’s All Greek to Me is more than a history lesson; it’s a lens through which we can re-examine our own society. Charlotte Higgins encourages readers to look back not out of nostalgia, but to better grasp the ideas and traditions that still shape the present. In a world grappling with democracy, truth, and the role of art, the Greek legacy remains astonishingly relevant.

🧠 Quotes from

It’s All Greek to Me

by Charlotte Higgins

- “We may no longer worship Zeus or sacrifice to Athena, but we live among their shadows.”

- “The Greeks gave us not just stories, but frameworks of thought—ways of arguing, imagining, and understanding the world.”

- “Tragedy isn’t about despair—it’s about recognizing human limits and the dangers of hubris.”

- “When we say someone has an ‘Achilles’ heel’, we are invoking an ancient truth: that greatness and vulnerability often coexist.”

- “Democracy, like theater, was an act of participation—performed in public, shaped by persuasion.”

- “To learn Greek was once to join a cultural elite. Today, it’s a way to decode the DNA of Western civilization.”

- “Greek gods behaved badly, but their stories helped humans make sense of their own messy emotions.”

- “What Freud called the Oedipus complex, the Greeks called fate.”

- “Oratory was not just speech—it was power. The Greeks understood the magic of language to lead, seduce, and manipulate.”

- “From Homer to Hollywood, Greek myths provide the scaffolding for our greatest narratives.”

- “In Athens, questioning was a civic virtue. Socrates’ ‘why’ echoes through every classroom today.”

- “The Marathon is more than a race—it’s a myth we run to prove ourselves heroic.”

- “We are not just the heirs of Greek culture. We are its reenactors, reciting its lines anew each generation.”

- “Comedy and tragedy were not just genres—they were lenses through which the Greeks saw the world.”

- “When we debate, vote, protest, or perform—we are, in a way, speaking Greek.”

- “The Greek legacy is not marble and ruins. It’s questions, contradictions, and the urge to understand.”

- “The alphabet we use, the politics we practice, the dramas we stage—all bear the mark of Greece.”

- “To say ‘It’s all Greek to me’ is ironically true—we are immersed in Greekness more than we know.”

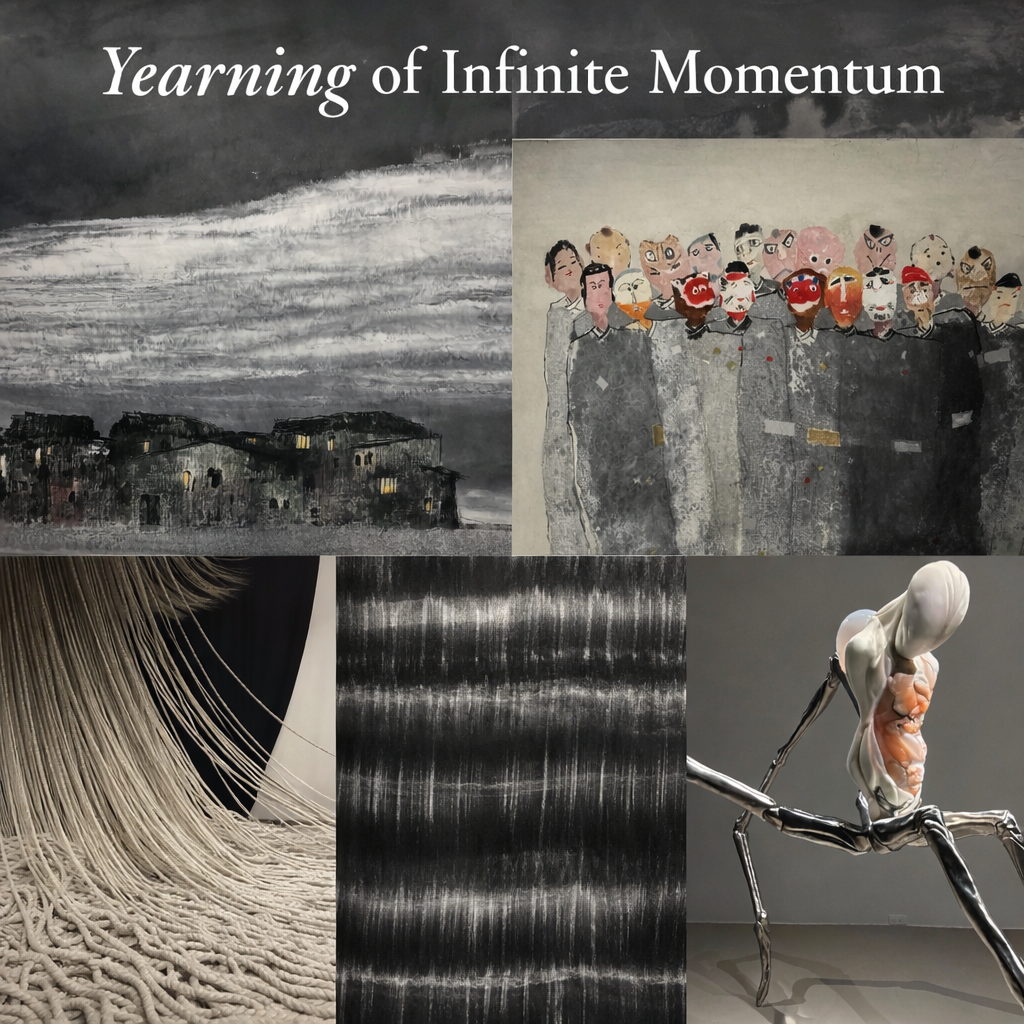

Yearning in Slow Motion

ChatGPT:

The Infinite Momentum of Yearning — Notes from a Seasoned Museum Wanderer

Museums are where I go to breathe. Not just to see art, but to see how others try to make sense of the world — sometimes through quiet poetry, sometimes through sheer visual noise. So when I found myself standing in the 2025 Taipei Biennial, themed Whispers on the Horizon: The Infinite Momentum of Yearning, I was both curious and skeptical.

Yearning? Momentum? Infinite?

That’s quite a lot of verbs and metaphysics for one afternoon.

But art doesn’t explain itself. It leans. It hovers. It waits for you to meet it somewhere in the middle — and this exhibition, despite its lofty title, did just that. It opened a quiet dialogue across space, time, longing, and what it means to keep moving — not necessarily forward, but inward.

1. Weighted Pause — The Architecture of Slowness

Afra Al Dhaheri’s installation of thick cascading ropes, Weighted Pause, offered a first whisper. The ropes were not decorative; they slumped with intent, grounded by their own weight. The space invited stillness — not absence, but presence. Slowness as ritual. Reflection as structure.

This wasn’t yearning as reaching. It was yearning as settling into — the kind that draws you down into yourself, like gravity made emotional.

The installation didn’t ask for interpretation. It asked for a pause. And in that pause, the idea of “momentum” became paradoxical — something that doesn’t always look like motion, but like still weight pulling toward meaning.

2. Destroy Your Home, Build Up a Boat, Save Life — On Departure and Survival

A carpet, rolled and stacked like half-forgotten scrolls. Hera Büyüktaşçıyan’s work borrowed its title from an ancient Mesopotamian flood story, but the story felt utterly modern: break what you’ve built, leave what you’ve loved, survive.

Here, yearning wasn’t nostalgic. It was brutally practical. If the home cannot hold, then it must become vessel. This kind of transformation doesn’t float gently — it scrapes. The soft textile of the carpet became a survival tool — and with that, an unexpected symbol of resilience disguised as surrender.

It spoke of memory, but in a language that doesn’t comfort — one that rolls itself up and moves on.

3. Clouds in the Dusk — The Quiet Gravity of Ink

Some works whisper louder than others. Ho Huai-Shuo’s Clouds in the Dusk used traditional ink wash to depict fading rooftops under a dense sky, yet it wasn’t nostalgia I felt — it was grief. Not loud, not dramatic — but soaked into the paper like weather that never lifted.

The sky loomed heavy with untold stories. The clouds weren’t metaphor — they were memory blurred by distance. It wasn’t about returning home. It was about standing under the weight of things you’ve lost the words for.

If yearning has a visual language, this was one: subdued, layered, dissolving at the edges, refusing to resolve.

4. I Had Reached the Nothing… — Transformation Without Promise

Ivana Bašić’s unsettling figure — part creature, part human — stood mid-transformation. The sculpture’s title evoked desolation: I had seen the centuries, and the vast dry lands…, yet what I saw wasn’t “nothingness.” It was a body caught in a process too deep for comfort, too slow for drama.

There was no “becoming” in the elegant sense — no butterflies or revelations. Just tension, mutation, soft organs exposed, and metal limbs braced for unknown terrain.

It reflected a different kind of yearning: not for future or past, but for structure in flux. A reaching toward meaning with no map, only instinct.

5. The Masked People — Echoes of Theater and Control

Yuan Chin-Ta’s The Masked People was a curious, crowded watercolor: figures in muted uniforms, each wearing a comically distinct mask. It evoked folk puppetry, political performance, and bureaucratic absurdity — all at once.

Painted a year after martial law was lifted in Taiwan, the work captured the moment between suppression and expression. The masks, instead of hiding, seemed to amplify the falseness of what they covered.

Yearning here was sociopolitical — not for truth, but for the right to shed layers. To step off the stage and be uncast. It was not a question of identity, but of what happens when identity is no longer assigned.

6. Vertical Timeless — Rhythm, Fragility, and the Tension of Repair

Minjung Kim’s work, a large-scale composition made from torn and burnt Hanji paper, offered one of the most meditative interpretations of the exhibition’s theme. The vertical bands of ink and fiber resembled sound waves, or perhaps seismic readings of an emotional landscape.

Kim’s meticulous layering and gentle damage showed yearning as both destruction and recovery — the contradiction of continuity. Her method — staining, tearing, mending — became a form of prayer.

No manifesto. No bold color. Just rhythm and rupture, stitched into something quietly relentless.

Closing Thoughts: Not All Longing Looks the Same

What this exhibition reminded me is that yearning does not always scream, strive, or stretch. Sometimes it sits quietly. Sometimes it folds. Sometimes it transforms without permission.

If momentum exists in these works, it is not about arrival. It is about the movement within holding still. The slow persistence of searching. Of repairing. Of remembering.

The horizon remains unreachable. But maybe that’s the point. We are not meant to arrive — only to continue.

And what a beautiful, baffling thing that is.

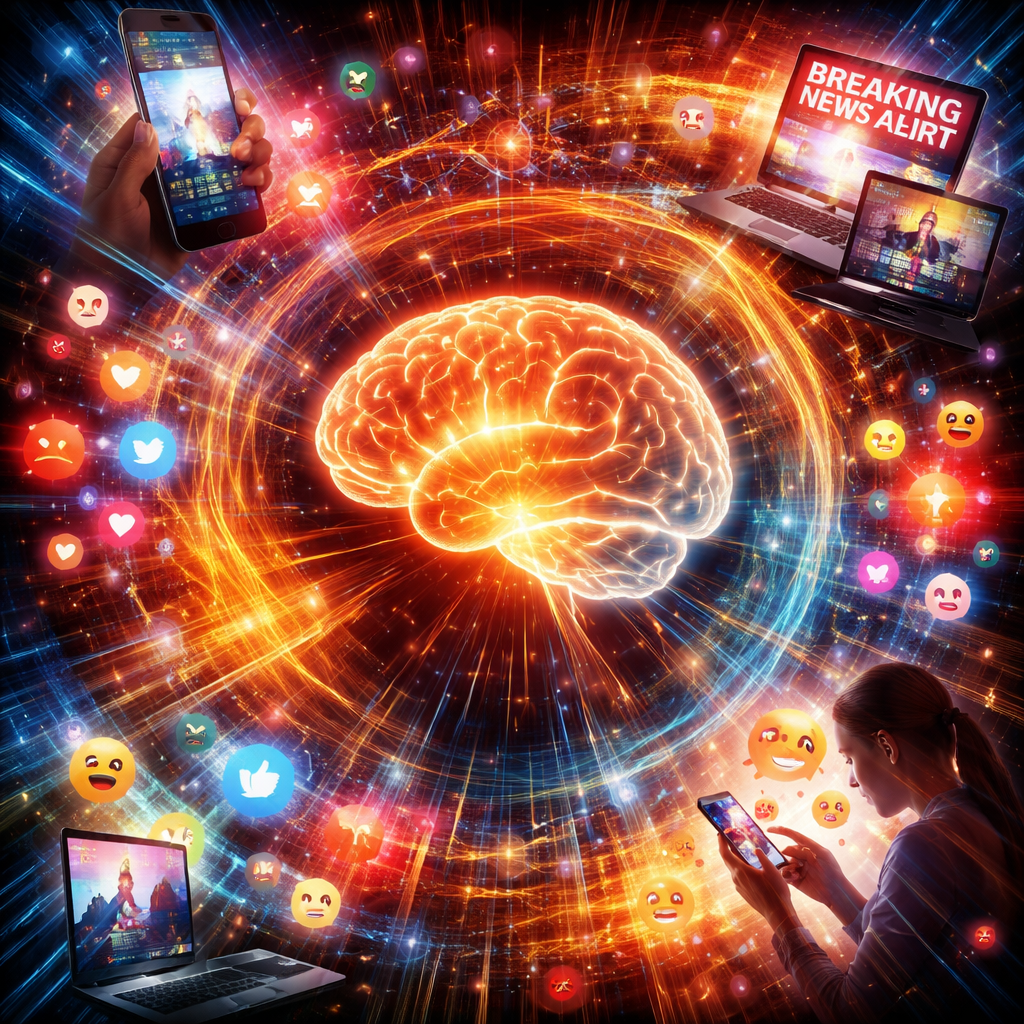

What Grabs Your Mind: The Salience Network in an Age of Endless News

ChatGPT:

🧠 The Salience Network: Why Some Things Grab Us—and How to Stay Engaged Without Being Hijacked

1️⃣ What is the Salience Network?

- The Salience Network (SN) is one of the brain’s core large-scale networks.

- Its job is simple but powerful:

To decide what matters right now. - It continuously scans:

- The outside world (sounds, faces, threats, novelty)

- The inside world (pain, emotions, bodily signals)

- When something “jumps out,” the SN flags it as salient and reallocates attention.

Key brain regions

- Anterior insula: integrates bodily feelings and emotional signals

- Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC): monitors conflict, urgency, and need for action

- Together, they act like a neural spotlight operator, deciding what breaks through background noise.

📌 Importantly, the SN does not judge truth, morality, or long-term value.

It only answers: “Does this demand attention now?”

2️⃣ What happens when the Salience Network malfunctions?

Underactive SN

- Emotional blunting

- Indifference

- Reduced urgency or concern

- Seen in:

- Certain neurodegenerative diseases

- Advanced Parkinson’s

- Severe depression

Overactive SN

- Hypervigilance

- Anxiety

- Emotional flooding

- Difficulty disengaging from alarming information

- Seen in:

- Chronic stress

- PTSD

- Doomscrolling behavior

📌 Most modern problems come not from a broken SN, but from an overstimulated one.

3️⃣ Aging and the Salience Network

- In healthy aging:

- The SN often becomes less reactive

- Emotional hijacking decreases

- People respond more selectively

- This is not decline—it is often recalibration.

- However:

- Executive control (the brain’s “brakes”) may fatigue faster

- Meaning-seeking increases

- Moral concern for society and future generations deepens

📌 These changes make seniors less impulsive, but sometimes more vulnerable to prolonged worry, especially when media repeatedly signals threat and urgency.

4️⃣ Why modern media hacks the Salience Network so effectively

Modern media is almost perfectly engineered to trigger SN alarms.

It exploits SN’s evolutionary triggers:

- Novelty: breaking news, shocking headlines

- Threat: fear, outrage, moral violation

- Social relevance: likes, shares, reputation, identity

- Unpredictability: infinite scroll, variable rewards

Why this works

- SN activation happens in milliseconds

- Rational evaluation comes later

- By the time we think “this is exaggerated,” attention has already been captured

📌 Media doesn’t need to be true—only salient.

5️⃣ Why some people resist media salience better than others

Resistance is not willpower or intelligence.

Key protective factors:

- Strong executive regulation: better “braking” of emotional capture

- Stable values: clear sense of what truly matters

- Long time horizons: less urgency about every event

- Low-threat developmental history: higher salience threshold

- Training in slow attention:

- Long-form reading

- Science, philosophy, music

- Reflective or contemplative practices

📌 Salience resistance is a network balance, not a personality trait.

6️⃣ How to protect the Salience Network without disengaging from the world

The goal is not numbness or withdrawal, but salience hygiene.

Core principles

- Protect accuracy, not calm

- Reduce false urgency, not real concern

- Let meaning—not novelty—decide attention

Practical strategies

- Control entry points:

- Turn off non-human notifications

- Batch news into predictable windows

- Slow the first reaction:

- Pause

- Name the trigger (“fear,” “outrage,” “novelty”)

- Use context:

- Ask “Is this noise or signal over years, not hours?”

- Strengthen executive control:

- Sleep

- Single-tasking

- One cognitively demanding activity daily

- Replace outrage with compassionate action:

- Small, local, meaningful responses

📌 Attention is not obligation.

7️⃣ Media diets for cognitive aging: avoiding doomscrolling

Doomscrolling often appears after retirement because:

- Time structure disappears

- Moral vigilance increases

- Media becomes the default filler

Think of media like nutrition

🟥 Ultra-processed media (limit sharply)

- 24-hour news

- Algorithmic outrage feeds

- Endless short videos

→ Overstimulates SN, exhausts executive control

🟧 Processed media (structured use)

- One newspaper

- One scheduled news program

→ Information without overload

🟨 Whole media (protective)

- Books

- Essays

- History, philosophy

- Long interviews

→ Restores narrative time and meaning

🟩 Regenerative media (actively beneficial)

- Music

- Arts

- Nature programs

- Calm educational content

→ Calms SN, strengthens emotional regulation

A healthy daily “media plate”

- 🟩 Regenerative: 40%

- 🟨 Whole / long-form: 30%

- 🟧 Structured news: 20%

- 🟥 Ultra-processed: <10%

🔟 Final synthesis

The Salience Network is the brain’s relevance detector—essential for survival, empathy, and engagement. In a media-saturated world, protecting it requires structure, meaning, values, and compassion—not withdrawal. Especially in aging, the goal is not to stop caring, but to care wisely.

42 Reasons Sci-Fi Rules the World

ChatGPT:

Don’t Panic: The World Is Still Ending, Just Smarter Now

🚀 Science Fiction: The Genre That Built the Future

Science fiction is often dismissed as mere escapism — aliens, lasers, time travel, and people yelling “We’ve got to reverse the polarity!” But behind the imaginative chaos lies something deeper:

Science fiction isn’t just entertainment. It’s a blueprint for the future — one that engineers, scientists, tech founders, and entire subcultures quietly follow.

From space missions to AI ethics, from smartphones to meme culture, sci-fi has shaped the modern world more than most history books dare to admit.

Here’s how — in plain English, for humans and intelligent machines alike.

🌌 Science Fiction and Space Exploration

Science fiction didn’t just predict the space race — it inspired it.

- Star Trek (1966) showed a peaceful, exploratory vision of space travel that inspired generations of NASA scientists and astronauts.

- The communicator? Inspired flip phones.

- The tricorder? Inspired portable diagnostic tools.

- The warp drive? Still theoretical — but being actively researched by physicists (seriously).

- Arthur C. Clarke, author of 2001: A Space Odyssey, accurately predicted satellites and geostationary orbit before they existed. NASA engineers still cite him as a major influence.

- The Martian by Andy Weir became required reading in some engineering classes for its accuracy and realism.

- NASA used the book to promote interest in Mars missions.

- It made orbital mechanics and botany cool — somehow.

“Science fiction has always been the unofficial PR department for space agencies.” – Everyone at NASA, probably

🌐 Sci-Fi and the Birth of the Internet

Before Google or Reddit existed, sci-fi authors imagined entire information ecosystems.

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Douglas Adams):

- Predicted a portable digital encyclopedia with user-generated content — basically Wikipedia with jokes.

- Also had smart assistants, infinite search, and unreliable answers… eerily familiar.

- Neuromancer (William Gibson):

- Invented the word “cyberspace” in 1984.

- Inspired the visual language of the web, hacker culture, and the aesthetic of everything from The Matrix to cybersecurity ads.

- H2G2.com, created by Adams in the ’90s, was one of the first public attempts at crowd-sourced internet knowledge — a proto-Wikipedia built for humor, curiosity, and towels.

Sci-fi imagined the internet before the internet knew what it wanted to be.

🤖 Sci-Fi and Artificial Intelligence

Science fiction helped us think about thinking machines long before ChatGPT ever offered you snarky commentary.

- HAL 9000 (2001: A Space Odyssey) — the original AI nightmare.

- Calm, polite, and willing to murder astronauts if they interfered with the mission.

- HAL became a case study in AI ethics and control.

- I, Robot (Isaac Asimov):

- Introduced the famous Three Laws of Robotics, which have influenced real-world AI policy and philosophy debates.

- Ex Machina, Her, and Westworld:

- Ask unsettling questions about machine consciousness, human emotion, and free will.

- These narratives shape how we discuss AI rights, autonomy, and danger in tech spaces today.

Fictional AI made real-world AI developers paranoid — and that’s a good thing.

🎭 Sci-Fi as Cultural Catalyst

Sci-fi doesn’t just shape gadgets — it reshapes how we think about ourselves.

- The Left Hand of Darkness (Ursula K. Le Guin):

- Imagined a society without fixed gender — decades before “non-binary” became part of common discourse.

- It’s now studied in university courses on gender, sociology, and speculative anthropology.

- Black Panther and Afrofuturism:

- Combines sci-fi with African history, mythology, and technology to envision decolonized futures.

- Reframes what innovation looks like — and who gets to participate in it.

- Everything Everywhere All At Once:

- Explores multiverse theory, mental health, immigrant identity, and absurdist philosophy — all in googly-eyed hot dog finger style.

- It’s proof that sci-fi isn’t “just about the future.” It’s about every possible version of now.

Sci-fi reflects us at our weirdest — and best.

📚 Science Fiction Creates the People Who Create the Future

Ask tech leaders, astronauts, or AI researchers what inspired them — they’ll say sci-fi.

- Elon Musk constantly references The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Foundation.

- Google’s founders loved Snow Crash, Rama, and Ender’s Game.

- Scientists and engineers have used sci-fi not only to imagine future problems, but to test solutions in their minds before they become real.

Science fiction doesn’t predict the future — it trains the people who will build it.

✨ Final Thoughts

Science fiction is not just for nerds (though we thank them for carrying the genre since 1926). It’s a creative force that:

- Imagines the impossible,

- Critiques the probable,

- And inspires the achievable.

In the lab, in the launchpad, on the internet, and in your phone — sci-fi was there first.

So next time someone tells you science fiction is just escapism, you can smile gently and say:

“So was the moon landing… until it wasn’t.”

Now go read something with lasers. Or dolphins. Or depressed robots. The future depends on it.

Why Your Brain Never Rests—And What Happens With Age

ChatGPT:

🧠 Understanding the Brain’s Default Mode Network — And How Aging Changes It

The Default Mode Network (DMN) is a fascinating and essential part of how your brain works when you’re not actively focused on the outside world. It’s responsible for what you might call your “mental background noise”: thoughts about yourself, your memories, your future plans, and even what others are thinking. But as we age, this vital brain system undergoes changes that can affect memory, attention, and emotional health.

This guide will help you understand what the DMN is, what brain areas it includes, and how aging impacts its functions.

🧠 What is the Default Mode Network (DMN)?

- The DMN is a brain network that becomes more active during rest, daydreaming, and self-reflection—basically, when you’re not focusing on a specific task.

- It’s the system behind:

- Thinking about yourself or your life story.

- Remembering the past and imagining the future.

- Understanding others’ feelings and thoughts (social thinking).

- Planning, reflecting, and daydreaming.

🧩 Why the DMN Matters

- Though it operates in the background, the DMN is not idle—it’s deeply involved in your personality, memories, and emotions.

- It’s responsible for helping you construct a sense of self, mentally time travel, and empathize with others.

- Scientists believe it helps the brain predict outcomes based on past experiences.

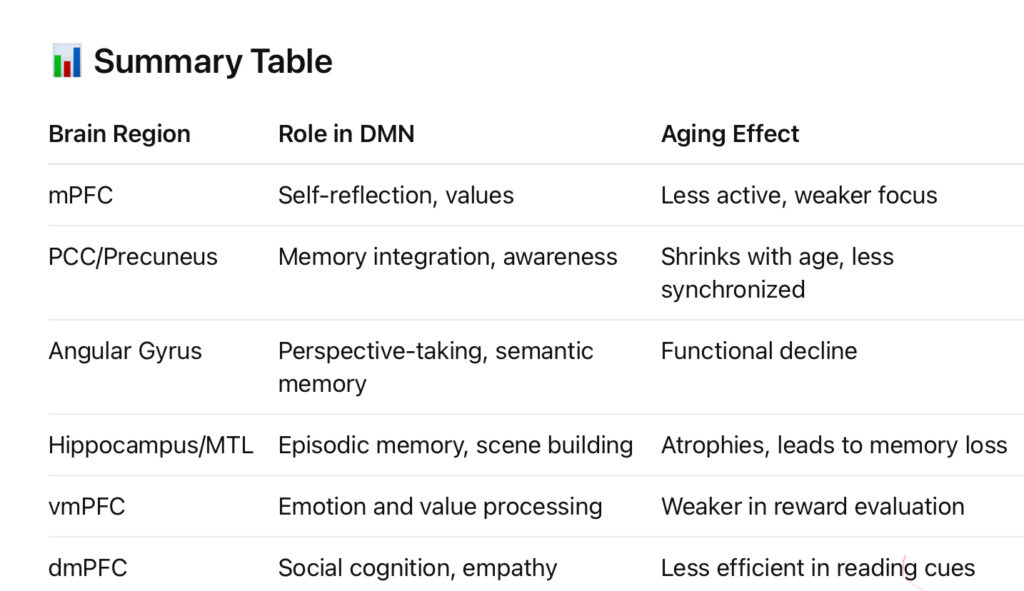

🧬 Key Brain Areas of the DMN

Each part of the DMN plays a unique role in supporting internal thought:

🧠 Core Brain Regions and What They Do:

- Medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC):

- Reflects on self-related thoughts and personal decisions.

- Supports emotional evaluation and moral reasoning.

- Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC) / Precuneus:

- Central for remembering the past and constructing mental scenes.

- Integrates memories into a coherent “narrative” of the self.

- Angular Gyrus:

- Connects sensory experiences to language and memory.

- Helps you take different perspectives and interpret meaning.

- Hippocampus & Medial Temporal Lobes (MTL):

- Vital for memory, imagining future events, and spatial navigation.

- Links emotions with memories.

- Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex (vmPFC):

- Assigns emotional value to thoughts and memories.

- Helps process rewards and outcomes of decisions.

- Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex (dmPFC):

- Key in understanding social cues and what others might be thinking.

- Supports empathy and social decision-making.

- Retrosplenial Cortex (RSC):

- Handles spatial orientation and connects memory with sensory input.

- Temporal Poles & Lateral Temporal Cortex:

- Provide emotional depth and conceptual knowledge.

- Process stories, social emotions, and relationships.

👵🏽 How Aging Affects the DMN

As we grow older, the brain doesn’t shut down the DMN—but it changes how it works, often reducing its efficiency. Here’s how:

🧓 Aging Effects on DMN:

- Reduced Functional Connectivity:

- The parts of the DMN stop communicating as smoothly.

- This makes it harder to maintain consistent internal thoughts or recall details clearly.

- Brain Shrinkage (Atrophy):

- Regions like the hippocampus and PCC shrink with age.

- This affects both memory strength and emotional stability.

- Harder Time Switching Tasks:

- Normally, the DMN “turns off” when you need to focus.

- In older adults, it stays active longer—causing distractions, slower reactions, or mind-wandering during tasks.

- Memory Lapses & Mental Fatigue:

- As DMN activation patterns become less distinct, it becomes easier to forget things or feel mentally tired.

- Greater Alzheimer’s Risk:

- DMN regions are among the first to show amyloid plaque buildup in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Changes in DMN function can predict cognitive decline even before symptoms appear.

- Increased Mental Noise:

- The DMN may become more intrusive, making it hard to focus or stay organized.

- Compensatory Brain Activity:

- Some older adults activate other brain networks to make up for DMN inefficiency.

- This is a sign of the brain’s plasticity—its ability to adapt.

💡 Final Thoughts

- The Default Mode Network is your internal thought engine—guiding who you are, how you remember, and how you relate to others.

- While aging affects this system, understanding these changes is the first step toward protecting brain health.

- Activities like meditation, learning, social interaction, and physical exercise can help preserve DMN function.

Seoul, Taipei, and the Secret to Aging

ChatGPT:

Aging Well Beyond Health: What We Can Learn From South Korea and Taipei’s Seniors

Aging is inevitable. With luck, we’ll all get there. But the real question isn’t whether we’ll grow old — it’s how. And while doctors and fitness apps keep reminding us about the importance of diet, medication, and exercise, modern research in gerontology (the study of aging) is giving us something much more human to consider:

Wellbeing in later life depends just as much on social, emotional, and psychological factors as it does on physical health.

Let’s take a look at six key non-physical ingredients for a good life in old age — and how communities in South Korea and Taipei are showing the rest of us how to do it right.

⸻

🧠 1. Cognitive Engagement – Keep the Mind Moving

• The brain is like a muscle: if you don’t use it, it weakens.

• Studies show that seniors who stay mentally active — through learning, hobbies, music, and memory-based activities — are more likely to maintain cognitive health.

Real-world example:

• At Hollywood Classic Theater in Seoul, many seniors come not just to watch old movies, but to remember. They rewatch classics from their youth, replay old soundtracks in their heads, and keep their minds connected to memory, story, and culture.

• In Taipei, seniors join singing groups, karaoke circles, and even museum volunteer programs (yes, they have to pass a test to qualify — and they love it).

⸻

🤝 2. Social Connection – No One Thrives Alone

• Loneliness isn’t just unpleasant — it’s dangerous. Social isolation is linked to depression, faster physical decline, and even premature death.

• A thriving social life gives seniors emotional support, motivation, and a reason to show up.

Real-world example:

• The Seoul theater is more than a cinema — it’s a social hub. People come alone, yes, but they come together — talking, dozing off, sharing a routine.

• In Taipei, mornings are filled with seniors dancing, stretching, or singing in the parks. They later regroup in malls, IKEA cafés (thanks to unlimited refills), and local markets — not for shopping, but for togetherness.

⸻

🎯 3. Purpose – A Reason to Wake Up

• Retirement often strips people of their roles and identity. A sense of purpose — however small — can radically improve mental health and even increase lifespan.

• Purpose might come from caring for others, helping the community, learning new things, or simply having daily rituals.

Real-world example:

• Seoul’s Mr. Kim, an 81-year-old retired foreman, goes to the movie theater two or three times a week. It’s part of his daily rhythm, like checking his step count or chatting with the ticket checker.

• Taipei seniors often volunteer at museums, attend cultural events, or simply follow a self-made schedule of park visits and shared meals. That structure becomes their purpose.

⸻

🧘 4. Psychological Resilience – The Inner Armor

• Aging comes with losses: of loved ones, roles, health, and sometimes independence.

• Resilient seniors don’t avoid grief — they adapt to it. They find joy in small things and keep going.

Real-world example:

• Many of Seoul’s theater regulars have experienced deep solitude, but they continue to show up. Some even nap through half the film and return again the next day.

• In rural Taiwan, seniors who live alone find comfort in community lunch kitchens, where for around $2, they receive a hot meal and human contact — a simple but powerful buffer against isolation.

⸻

👨⚖️ 5. Autonomy – Having Control Over One’s Life

• Even minor decisions — when to eat, where to sit, what to do today — matter deeply.

• Autonomy reinforces dignity and confidence.

Real-world example:

• At the Seoul theater, seniors pay their own tiny ticket fee, choose which films to watch, and stay (or leave) as they like. That control, however small, is sacred.

• In Taipei’s parks, seniors create their own groups. No one tells them when or how to move — they run their own show.

⸻

🌟 6. Dignity and Respect – Aging With Grace

• Older adults want to feel valued, not invisible. Respect and inclusion are essential to mental health.

• Societies that treat seniors as cultural assets — not as burdens — have healthier, happier older populations.

Real-world example:

• The theater owner in Seoul, Ms. Kim, rebuilt the cinema not for profit but to create a dignified space for aging citizens — one where they can be cultural participants, not forgotten relics.

• In Taipei, the sheer presence of seniors in public life — dancing in parks, chatting in IKEA, joining group lunches — reflects a culture that hasn’t hidden its elders away.

⸻

🧾 Conclusion: What Can We Learn?

If aging is a universal experience, then the quality of that experience is a social choice. What Seoul and Taipei show us is that:

• Aging well is not about luxury — it’s about infrastructure, creativity, and respect.

• A movie theater can be a mental health center. A park can be a stage for social connection. A $2 lunch box can be a powerful form of eldercare.

• Seniors don’t need much: a safe place to gather, something to look forward to, and a society that sees them.

⸻