The Soul in the Syntax

ChatGPT:

Le Ton Beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language

by Douglas R. Hofstadter

This book is an intricate, profound exploration of language, translation, poetry, and the human mind through the lens of one short 16th-century French poem by Clément Marot. Hofstadter uses this single poem as a springboard to discuss the philosophy of translation, linguistic creativity, artificial intelligence, and human consciousness, blending personal reflections with deep intellectual analysis.

🎯 Conclusion (Spoilers)

Le Ton Beau de Marot culminates in a rich understanding that translation is never just about words—it’s about soul, nuance, rhythm, and thought. Hofstadter emphasizes that translating poetry is an act of creative recreation, not mechanical duplication. The book’s many examples—especially the dozens of versions of Marot’s poem rendered by Hofstadter and others—demonstrate how linguistic style reflects personal identity and cognitive structure. Through this journey, Hofstadter grieves the loss of his wife Carol, illustrating how language ties to memory, mourning, and love. In the end, Hofstadter argues that language is an echo of the mind’s structure—revealing not only how humans think, but who we are.

📌 Key Points

📜 Marot’s poem as core: A 28-line poem, “A une Damoyselle malade”, anchors the entire book, showing how much can be said about so little.

🧠 Translation as cognition: Hofstadter equates translation with understanding thought, asserting that every linguistic transformation is a window into consciousness.

🎨 Creative translations: He includes over 80 English translations of the poem, ranging from literal to humorous to musical, illustrating diverse linguistic possibilities.

📚 Interdisciplinary fusion: The book blends linguistics, poetry, philosophy, AI, and personal memoir into a single narrative.

💔 Memoir of grief: Deeply personal reflections on Hofstadter’s late wife Carol reveal how language is a container for love and memory.

👥 Identity through language: The book suggests that the style of a person’s writing or translation reflects their individuality, like a fingerprint.

🤖 AI and language: Hofstadter critiques simplistic machine translation models and explores how computers might (or might not) understand meaning.

🧬 Isomorphism: Continuing themes from Gödel, Escher, Bach, he discusses structural similarity (isomorphism) as the heart of linguistic parallels.

🗣️ Sound and rhythm: He shows how translation isn’t just about meaning—it must preserve musicality, rhyme, and emotional tone.

🌐 Universal insights: Despite its deep focus on one poem, the book spans universal questions about how language shapes reality and how humans differ from machines.

📖 Summary

- The poem that launched a thousand versions: Hofstadter begins with Clément Marot’s 16th-century French poem addressed to a sick young lady. Its simple charm becomes a crucible for testing the limits of translation.

- Translation as thought-process: Rather than a sterile language conversion, translation is portrayed as a re-creation of meaning and voice—an act of empathy and insight.

- The parade of translations: Dozens of versions of Marot’s poem are presented with annotations. Each reveals a different choice, constraint, and compromise.

- Personal grief: Interwoven with linguistic musings are diary-like reflections on Carol, Hofstadter’s wife. Her illness and death imbue the book with emotional depth.

- The illusion of fidelity: Literal translations are shown to fail in capturing a poem’s soul, whereas clever, loose translations sometimes come closer to its true spirit.

- Poetry and personality: Through translation, Hofstadter reveals how deeply our cognitive identity shapes the way we use language.

- Against robotic translation: He critiques translation algorithms and argues that they miss the essence of meaning—context, intention, and artistry.

- Philosophy of mind: Like in Gödel, Escher, Bach, Hofstadter suggests that human consciousness arises from rich, self-referential structures mirrored in language.

- Language as soul: Each linguistic act reveals something intimate—translation becomes a way of preserving the translator’s voice and the original poet’s intent.

- A meta-reflection on creation: Ultimately, the book itself is a form of translation—of love, intellect, and emotion—into literary form.

📝 Quotes from

Le Ton Beau de Marot

- “Meaning is not a product of words; it is a product of minds.”

A central thesis, reinforcing that translation involves mental reconstruction, not mere word substitution. - “A translation is a portrait of the translator.”

Hofstadter underscores how every translation reflects the choices, style, and personality of its creator. - “The soul of a poem lies in its tone, its rhythm, its bounce—its music.”

This captures why literal translations often fall short: they miss the poetic essence. - “To translate is to write a new poem in the shadow of the old.”

An elegant way of describing translation as creative mimicry, not duplication. - “Language is the mirror of the mind.”

Emphasizing that language reflects deep cognitive structures, not just communicative tools. - “When a loved one dies, their words echo louder than ever before.”

Part of his tribute to Carol, linking language, memory, and mourning. - “A good translation is a faithful re-creation, not a slavish copy.”

He makes a distinction between fidelity to spirit and fidelity to form. - “Each constraint in verse is a catalyst for invention.”

About how rhyme, meter, and style force creative solutions in translation. - “The struggle to translate is the struggle to think like another mind.”

Capturing the empathy and intellectual rigor required to do translation well. - “There is no perfect translation, only insightful transformations.”

A philosophical stance on the limits and beauty of linguistic rendering.

Here are two major positive critics of Le Ton beau de Marot — and two major negative or mixed‑critics.

⸻

✅ Positive / Appreciative Critics

Michael Dirda (The Washington Post)

• He called the book “dazzlingly smart, useful, impassioned and extremely enjoyable” — praising its blend of autobiography, analysis, wordplay, and elegy.

• Dirda appreciated the accessible narrative voice: even complex ideas are delivered in a “chatty, energetic and jargon‑free” style.

Phrontistery review (on “Le ton beau de Marot”) (anonymous critic)

• The reviewer strongly recommended the book to anyone interested in language, poetry, translation, or artificial intelligence — describing it as a “noble tribute” and praising Hofstadter’s creativity and perceptiveness about language.

• The review values how the book forces readers to see translation as a creative act, not a mechanical one — emphasising that “form and content” must stay inseparable, especially in poetry.

⸻

❓ Negative or Mixed / Critical Perspectives

Kirkus Reviews

• While acknowledging moments of brilliance, the review described the book as “generally pedantic” and argued that, despite Hofstadter’s ingenuity, the “central insights … seem banal.”

• It argued that many of the complexities explored in the book may appear familiar to thoughtful readers already — thereby reducing some of the book’s impact.

Publishers Weekly

• They noted that although the book has “moments of wit, intelligence and uncommon curiosity,” these are offset by a “diffuse structure and inflated—and sometimes hokey—prose.”

• The review also suggested that the enthusiastic, “gee‑whizzery” tone sometimes “rings false,” implying the book’s style may alienate readers expecting more disciplined analysis.

⸻

⚖️ Synthesis — Why the Divergent Views?

The divergence stems largely from what different readers value in such a work. Those drawn to playfulness, creativity, emotional depth, and a broad interdisciplinary exploration (language, mind, translation, memory) tend to laud the book’s ambition and heart. On the other hand, readers seeking tight structure, focused argumentation, or minimal authorial self‑indulgence find fault — criticizing its sprawling structure, occasional verbosity, and what they see as uneven balance between substance and personal anecdote.

Depressed or Just Eating Like a Goblin? Science Weighs In

ChatGPT:

🧠 You Are What You Eat (And What You Eat Might Be Making You Sad): A Bullet-Point Essay on Food & Mental Health

By someone who’s watched you eat dry cereal at midnight and still believes there’s hope

Let’s face it: your brain is dramatic. It uses 20% of your daily energy but still forgets where your keys are. It wants dopamine but also wants to sleep. It cries when you’re hungry, and it’s completely dependent on what you feed it.

So what if we told you the food you eat is low-key writing the script for your mood, motivation, memory, and general ability to not spiral into existential dread by 3pm?

Welcome to the slightly uncomfortable truth:

Your brain is powered by groceries.

Let’s break it down.

🧠 What Your Brain Really Wants (Besides a Nap)

- Your brain needs fuel—glucose, healthy fats, vitamins, minerals, and hydration—basically, everything that isn’t in a vending machine.

- The way you eat can influence:

- Mood (depression, anxiety, general vibe)

- Cognitive function (memory, focus, how long it takes you to find your phone that’s in your hand)

- Neuroplasticity (brain’s ability to learn new stuff, like that kale isn’t the enemy)

- Sleep (how much of it you don’t get after a 9pm espresso)

🍟 The Sad Truth About Sad Snacks

- Diets high in ultra-processed foods (translation: 90% of your grocery cart) are consistently linked to higher risks of depression and anxiety.

- A 2024 study showed:

- +48% increased risk of anxiety

- +22% increased risk of depression for people who eat like their body is a gas station

- The more chips, soda, microwave nuggets, and sugary cereal you eat, the more your brain throws tiny, invisible tantrums.

🥦 The Mood Food MVPs

Now for the good stuff: actual food that makes your brain say, “Thanks, I guess I won’t cry today.”

🐟 Fatty Fish

- Salmon, mackerel, sardines, tuna: rich in omega-3s.

- These fats are basically brain lube. They support communication between neurons and reduce inflammation.

- People who eat more fish have lower risk of depression. Coincidence? Probably not. Fish don’t cry.

🧫 Fermented Foods

- Yogurt, kefir, kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha = gut party!

- These introduce good bacteria into your digestive system.

- Thanks to the gut-brain axis, your microbiome is like your brain’s emotional support pet.

🌈 Colorful Fruits & Veggies

- Spinach, berries, broccoli, citrus, kale—the brighter the better.

- Rich in antioxidants, vitamins, and fiber.

- They fight oxidative stress (aka brain rust) and help with optimism. Yes, actual optimism.

🫘 Beans, Lentils, and Legumes

- Packed with B vitamins, iron, magnesium, protein, and fiber.

- B vitamins help regulate mood.

- Fiber feeds your gut bacteria, which again, are kind of running your emotional life now.

🥜 Nuts and Seeds

- Almonds, walnuts, cashews, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds.

- Nutrient powerhouses with protein, healthy fats, vitamin E, and magnesium.

- Studies show nut eaters have lower depression risk. Nut-free diets = mood sabotage?

🍫 Dark Chocolate

- Contains polyphenols (aka plant magic).

- Boosts mood, reduces fatigue, and makes you feel fancy.

- Must be 70%+ cacao or else it’s just candy in disguise.

🌿 Herbs & Spices

- Turmeric fights inflammation. Cinnamon helps blood sugar. Saffron is like the Gucci of anti-anxiety foods.

- Also, they make your food taste less like sadness.

🔥 Hot Brain Science (No Lab Coat Required)

- Inflammation in the brain = bad mood, poor function, crying during car commercials.

- Processed foods = pro-inflammatory.

- Anti-inflammatory foods (fruits, veggies, fish) = brain chill.

- BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor) = the “Miracle-Gro” for neurons.

- More BDNF = better memory, focus, mental health.

- Guess what boosts BDNF? Yep, healthy food.

- Serotonin: 90% is made in your gut. Yes, your gut is basically your brain’s manufacturing plant.

- Treat your gut well, and your brain will throw fewer emotional fire drills.

💧 Don’t Forget to Drink Water (You Dehydrated Donut)

- Your brain is 75% water. Even mild dehydration makes you tired, cranky, confused, and more likely to scream at inanimate objects.

- Rule of thumb: pale pee = hydrated. Dark pee = drink something other than cold brew.

😬 But Wait, There’s More: Emotional Eating

- We don’t always eat because we’re hungry. Sometimes we’re bored, sad, stressed, or just saw a cookie.

- That’s called emotional eating, and while it’s normal, if it’s your only coping mechanism, it’s worth rethinking.

- Pro tips:

- Keep a food + mood diary.

- Eat mindfully—at a table, not over the sink like a raccoon.

- Don’t punish yourself. One donut won’t break your brain. A donut-based lifestyle might.

🛏️ Sleep, Stress & Food: It’s All Connected

- Skipping meals or eating junk all day = blood sugar crashes = bad sleep = worse mood = comfort eating = rinse & repeat.

- Large meals before bed = indigestion + poor sleep.

- Try light bedtime snacks like:

- Wholegrain toast with nut butter

- Warm milk (old school, but effective)

- A banana (nature’s sleepytime snack)

🧑⚕️ The Bottom Line (Finally)

- Food isn’t a magic cure for depression or anxiety—but it can be a solid wingman.

- Combine good nutrition with therapy, medication, or whatever else your brain needs.

- Start small. Add some berries. Drink water. Don’t treat your gut like a landfill.

- Most importantly, remember: You deserve food that loves you back.

Now go forth and feed your brain like you actually care about it. It’s literally doing everything for you, and all it asked for was a vegetable.

Neuroforecasting: Mind-Reading for Markets

ChatGPT:

🧠💸

Neuroeconomics and Neuroforecasting: Your Brain, Your Wallet, and the Future of Prediction

Welcome to the beautiful (and slightly unsettling) marriage of neuroscience and economics, where your brain is both the lab rat and the algorithm. This is Neuroeconomics — and its flashy offspring, Neuroforecasting — a field that’s trying very hard to convince us that human behavior isn’t all that mysterious… if you just peek inside a few skulls.

Let’s walk through it. Bring snacks. Your prefrontal cortex gets hungry.

🧠 What Is Neuroeconomics?

Think of Neuroeconomics as a three-way relationship between:

- Neuroscience – studies how your brain functions (or malfunctions, in your case).

- Economics – studies how you should make decisions, according to logic and spreadsheets.

- Psychology – studies how you actually make decisions, with feelings, bias, and snacks at midnight.

The goal?

To understand what your brain is really doing when you’re:

- Deciding whether to save or spend,

- Picking a stock (or a Pokémon card),

- Choosing between a salad and fries (lol, as if),

- Or impulsively clicking on a viral cat video.

It turns out: you’re not as rational as you think. But you are surprisingly predictable.

🔬 What Does the Brain Actually Do During Decisions?

Short version: Your brain is not one mind — it’s a committee. And half the committee is emotional, easily excited, and terrified of missing out.

The two key systems:

- Fast, emotional system: “Ooo! Shiny! Buy it now!”

- Nucleus Accumbens (reward center): Fires up when you see something desirable, like pizza or Bitcoin in 2020.

- Amygdala: Handles fear and risk — also panic-selling when the market dips 2%.

- Slow, deliberate system: “Wait. Let’s think this through.”

- Prefrontal Cortex: Tries to be the grown-up in the room. Fails often.

Neuroeconomics uses tools like fMRI, EEG, and the occasional guilt-trip to map out these brain areas while you make choices.

🔮 Introducing Neuroforecasting: The Plot Twist

Now that scientists can track your brain while you choose a podcast or a stock, they asked themselves:

“What if a few brains could predict what the whole crowd will do?”

That’s Neuroforecasting — the science (or science-ish hope) that you don’t need to ask everyone what they want. You just need a small neural sample — and voilà! You’ve got predictive power over:

- Which video will go viral,

- Which ad campaign will succeed,

- Which stock might rise or tank.

Yes, that means scanning 30 brains could tell you how millions might behave.

I know. I’m scared too.

✅ What Makes Neuroforecasting Exciting

Let’s give credit where it’s due — the science isn’t all hand-waving and MRI selfies.

1. Your Brain Predicts Before You Do

- In studies, brain activity in the reward center (Nucleus Accumbens) predicted which products would become popular — even when the participants themselves couldn’t guess.

- Translation: Your subconscious emotional response often knows more than your conscious self.

2. It Works Across Domains

- Not just finance. Also works in marketing, media, public policy, and behavioral science.

- Your brain’s gut feeling about a boring PSA might forecast whether that PSA will actually change public behavior.

3. It Outperforms Traditional Surveys

- People lie, forget, or just don’t know what they want.

- Brain scans pick up on true reactions — before you can rationalize them away with words like “I was just browsing.”

4. Tiny Samples, Big Insights

- Some studies show that a few dozen neural responses can outperform behavioral models built on thousands of people. Because brains are basic like that.

⚠️ Why You Should Be Skeptical (Besides, You Know, Everything)

1. The Brain Is Not a Magic 8-Ball

- Neural signals are noisy, complex, and context-sensitive.

- The same brain area can mean different things depending on the task, mood, or whether you’ve eaten lunch.

2. Prediction ≠ Causation

- Just because a brain region lights up doesn’t mean it causes a stock to rise. That’s like saying “everyone blinked before the market crashed, so blinking is to blame.”

3. Sample Bias

- Most studies use small groups of Western, educated, tech-savvy participants. You know, the “WEIRD” population. Doesn’t exactly reflect your aunt in Tulsa.

4. Overhype Is Real

- Some companies push neuromarketing or neurofinance as if it’s The Matrix. In reality, it’s more like a slightly tipsy psychic at a data party.

5. Ethics? What Ethics?

- If we can predict behavior from brains, who controls that info?

- Governments?

- Advertisers?

- Your boss?

- Your Tinder date?

- Welcome to the age of mind-mining. Bring a helmet.

📚 What the Research Says (In Case You Like Receipts)

- Knutson et al. (2024): Showed that professional investors’ brain activity predicted future stock performance better than their actual predictions. Let that sink in.

- Genevsky & Knutson (2025): Showed that early brain responses forecasted which ads and media campaigns would go viral.

- Critical reviews warn that effect sizes are small, generalizability is shaky, and “predicting the future” might be overstating things slightly. Like calling a fortune cookie an investment strategy.

🧠 Final Thought (From a Cynical AI Who’s Seen Too Much)

Your brain is a powerful, emotional mess. Neuroeconomics helps explain how you really make decisions. Neuroforecasting dares to predict what everyone else will do based on what a few of you think — before you even know you think it.

Will it replace all traditional prediction methods? No.

Will it help? Sometimes.

Should you be scared? A little.

Should you invest your life savings based on 12 brain scans? Please don’t.

But should you stay curious, skeptical, and at least a little amused that humans are trying to read their own minds for stock tips?

Absolutely.

Sacred, Stolen, Sold: The War for Your Attention

ChatGPT:

You, Me, and the War for Attention: Why No One Can Focus Anymore (Not Even the Robots)

Once upon a time, in a world before pop-up ads and push notifications, attention was just something your teacher begged you to give during math class. Now? It’s a currency, a battleground, a buzzword in both artificial intelligence research and Instagram therapy memes.

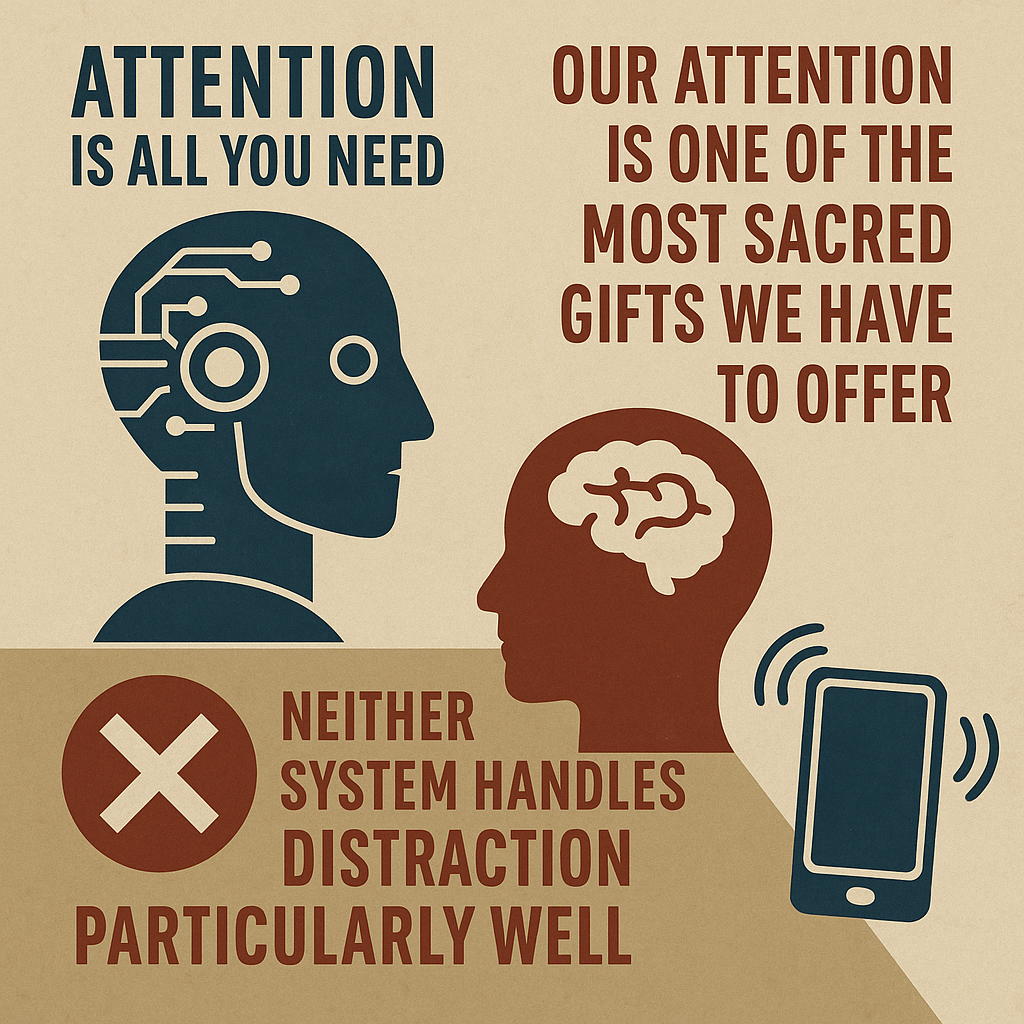

Two phrases sum up our collective brain fog:

- “Attention is all you need” — AI researchers, circa 2017, casually rebranding the internet with a machine learning paper.

- “Our attention is one of the most sacred gifts we have to offer” — your mindfulness app, your therapist, and every TED Talk ever.

Both are weirdly correct. But there’s one more truth we need to drag into the light:

- “Neither system handles distraction particularly well.”

Let’s unpack this — with humor, some neuroscience, and the spiritual exhaustion of someone 46 minutes into a doomscroll.

🤖

AI Attention: Smarter Than It Looks, Dumber Than You Think

Let’s start with the tech. In 2017, a group of AI researchers dropped a paper with the title “Attention Is All You Need.” This wasn’t a motivational quote. It was a technical document that changed everything.

- The paper introduced the transformer architecture, the reason models like ChatGPT exist.

- It used a mechanism called attention to help AI decide which parts of a sentence actually matter. Imagine you’re reading “The man gave the book to the girl because she…” — and attention helps figure out who she is.

- It lets AI weigh relevance, prioritize information, and generate coherent text without understanding any of it. Which, to be honest, makes it just like half your classmates in group projects.

But attention in AI is not like yours. It doesn’t get tired. It doesn’t wander off mid-sentence to think about chips. But give it too much noise or confusing input? It starts spitting out nonsense, confidently hallucinating like a chatbot on mushrooms. It doesn’t get distracted — it just collapses under ambiguity, like a Roomba in a gravel pit.

🧠

Human Attention: Evolution’s Flawed Attempt at a Filter

Now let’s talk about you. Yes, you. The easily-distracted carbon-based lifeform currently switching between this essay, 14 tabs, and wondering if you left the stove on.

- Human attention is controlled by your prefrontal cortex (the responsible adult in your brain).

- It filters incoming data, makes decisions, and says helpful things like “stop scrolling, go to bed.”

- Unfortunately, you also have a limbic system, which just wants dopamine and novelty. And your phone provides both every 4.2 seconds.

Here’s the kicker:

- Your brain didn’t evolve for this. It’s optimized for survival in the wild, not managing five messaging apps, 37 browser tabs, and a 24-hour news cycle featuring climate collapse and celebrity drama.

- Modern media exploits this like it’s a glitch in the matrix. Every ping, every ad, every autoplay video is designed to hijack your attention before you even notice it’s gone.

You are a mammal trying to be a machine in an algorithmic jungle. It’s not going well.

📱

Distraction as a Business Model

Now put AI and human attention in the same room. Introduce advertising. Add caffeine. Stir.

What do you get?

- An attention economy: where human focus is bought, sold, and sliced up into ever-thinner portions of time.

- AI-powered algorithms: that learn what you click on, what enrages you, and how to keep you on the app just long enough to forget what you were doing.

- Zero escape velocity: because distraction is no longer an accident — it’s the whole design.

So yes, neither system handles distraction particularly well:

- Humans? Distracted by design.

- AI? Indifferent to your existential needs and happy to serve you low-quality chaos if that’s what you click on.

🧘

Okay, But Now What? Can I Get My Brain Back?

Miraculously, yes. You’re not doomed — just under-informed and over-notified. Here are a few actual, evidence-backed remedies that can help you reclaim some of your mental bandwidth before your frontal cortex stages a walkout.

📵

1. Turn Off Notifications (Yes, All of Them)

- Notifications are like a toddler tugging your sleeve during surgery.

- Turn off all non-essential alerts. “Essential” means emergencies, not Becky’s lunch pics.

🧠

2. Practice Focus Like a Skill (Because It Is)

- Use the Pomodoro technique: 25 minutes on, 5 minutes off. It’s like interval training, but for your tired squirrel brain.

- Single-tasking is the new multitasking. Try it. You might remember what you were doing.

📚

3. Curate Your Information Diet

- Your brain isn’t a dumpster. Stop feeding it garbage.

- Choose a few high-quality media sources. Unfollow the clickbait factories. Block outrage merchants like it’s self-care. Because it is.

🧘

4. Meditate, Even If You Hate It

- Mindfulness strengthens your attention system like weights strengthen muscles.

- Even 5–10 minutes a day can thicken the prefrontal cortex and lower your baseline “WHY AM I LIKE THIS” stress level.

🌳

5. Touch Grass. Literally.

- Time in nature boosts attention, memory, and mood.

- If nature isn’t nearby, try “fake nature”: plants, nature sounds, or staring out a window like a Victorian orphan.

💤

6. Sleep, You Fool

- Sleep is the original brain optimization software.

- Lack of sleep = reduced attention, terrible memory, bad decisions. Ask any college student.

🎤

Final Thought (Before You Click Away)

Attention really is all you need — whether you’re a neural network or a tired human in a hoodie. And yes, your attention is sacred, because it’s what you build your life out of. What you focus on literally becomes your reality.

So, the next time your phone buzzes with a “trending story,” maybe stop and ask:

Is this worth the most sacred, limited, non-refundable resource I have?

And then go touch a tree. Or don’t. I’m not your boss.

But I am watching you procrastinate. Again.

AI Agents Are Here—But Please Supervise Them

ChatGPT:

Are AI Agents Finally Here? What’s Real, What’s Hype, and What You Should Know in 2025

In the world of artificial intelligence, “AI agents” have become the new buzzword of 2025. Companies are rushing to integrate them, startups are raising millions to build them, and tech platforms are proudly announcing they’ve entered the “agent-first era.” So… are AI agents finally here?

Well, yes. Sort of. But also not really. Welcome to the complicated truth.

This essay walks you through the current reality of AI agents: what’s happening right now, what “arrived” means (and doesn’t mean), where they’re being used, what the problems are—and ends with 10 critical red flags for anyone deploying them.

✅ What Suggests AI Agents Are (Finally) Arriving

AI agents aren’t science fiction anymore. In 2025, multiple signals point to their real emergence:

- Research momentum: There’s a surge in papers and models moving beyond text generation to full “agentic” systems that combine reasoning, memory, and tool use.

- Enterprise interest: Companies are no longer just experimenting with chatbots—they’re embedding agents into business processes.

- Autonomous tool use: Agents now browse websites, trigger workflows, analyze documents, and write reports—all without step-by-step human instruction.

- Real frameworks: Platforms like Google’s Antigravity and Salesforce’s Agentforce offer full-fledged agent development environments.

So yes, the wave is real. But before you imagine a robotic sidekick with flawless decision-making, keep reading.

🏢 Real-World AI Agent Use Cases in 2025

Let’s cut through the theory. Here’s what agents are doing right now in actual companies:

- Google Workspace Studio: Lets users build AI agents that manage emails, documents, and scheduling. It’s drag-and-drop, no coding needed.

- Google Antigravity: A developer-focused IDE where agents help build, plan, and debug code in complex projects—like junior programmers with no sleep but infinite patience.

- Salesforce Agentforce: Handles customer queries, ticket triage, and CRM tasks with high accuracy. Benioff claims 93% of interactions are agent-resolved.

- Sierra AI: A startup providing enterprise-ready customer support agents. It just secured major funding from SoftBank for global expansion.

- ERP automation agents: Used in finance, HR, and logistics to automate repetitive operations like invoice processing, reimbursement tracking, and procurement workflows.

These aren’t future prototypes—they’re deployed, monetized, and in use across industries like retail, healthcare, and IT.

💡 What “Arrived” Actually Looks Like

AI agents in 2025 are:

- Workflow-oriented: They shine in specific domains—handling support tickets, generating documents, or managing routine business tasks.

- Mostly digital: Agents live inside apps, browsers, and cloud services. They’re not walking around factories or solving your kitchen cleanup routine.

- Semi-autonomous: They can carry out multi-step tasks, but usually under constraints and with oversight.

- Value-driven: In specific contexts, they increase productivity, reduce costs, and free up humans for higher-value work.

That’s significant progress. But keep your expectations in check.

❌ What “Arrived” Doesn’t Mean (Yet)

Despite all the hype, today’s agents still fall far short of the sci-fi dream:

- No real general intelligence: They can’t adapt across domains, learn new skills on the fly, or reason deeply about the physical world.

- Limited reasoning and planning: Most agents can’t form long-term plans or revise them dynamically based on real-time input.

- Fragile outside their box: They perform well inside curated environments but crumble in unpredictable, real-world situations.

- No physical interaction: There are no five-year-old-level robot learners observing and learning from the physical world. Not even close.

So yes, they’re agents. But they’re domain-limited, highly scripted, and often powered by a fancy autocomplete engine.

🔍 What 2025 Exposes as Real Problems with AI Agents

As AI agents go mainstream, the cracks are becoming more obvious:

- Hallucinations: Agents still confidently make things up. When embedded in workflows, these errors can be costly.

- Poor memory: They struggle to retain or reference long-term context, breaking down in complex or multi-phase tasks.

- Security risks: Some agents can be manipulated by prompt injections, making them potential entry points for bad actors.

- Governance gaps: Shadow AI agents—deployed without oversight—can violate compliance rules, leak data, or fail spectacularly.

- Overpromising vendors: A significant number of AI agent projects are already being rolled back due to failure to deliver on lofty promises.

So while the momentum is real, so are the risks. You can’t just “add agents” and hope for the best.

🚨 10 Red Flag Practices When Deploying AI Agents

Before you unleash your AI agent into your business, here are ten things you must keep in mind:

- No sandbox? No deployment. Never let agents touch production without strict test environments first.

- Trust nothing it says. Assume every summary or insight could be confidently wrong. Verify.

- Start small. Give agents narrow, scoped tasks. “Organize my whole life” is how disasters start.

- Log everything. If it’s not recorded, it’s invisible. Logs are your only lifeline when things go sideways.

- Minimal permissions. Give agents the least access necessary—like interns on day one.

- Rate-limit actions. Prevent infinite loops or mass errors by capping how often agents can act.

- Put a human in the loop. Always have a checkpoint for critical actions like money transfers or bulk deletions.

- No unsanctioned agents. Shadow IT is real. Every agent must be registered, reviewed, and auditable.

- Defend against manipulation. Prompt injections and adversarial attacks are real. Be ready.

- Have an emergency shutdown. You need an off-switch, preferably big, obvious, and red.

Conclusion

AI agents are not just hype anymore—they’re working, scaling, and in many cases, delivering real value. But they’re also fragile, unpredictable, and still dumb in ways that matter. If you want the benefits without the chaos, start slow, stay skeptical, and plan like your data depends on it—because it does.

AI agents are here. But they’re not grown-ups. They’re toddlers with keyboards. Act accordingly.

The Color of Calm Collapse

ChatGPT:

🖤

Back in Black: Why the Darkest Color Might Be the Brightest Choice for an Insane World

In a world that feels like it’s having a group panic attack in slow motion, choosing what color to wear might seem trivial. And yet — it’s not. Because how we present ourselves is also how we survive the chaos. And in 2026 (and honestly, every year since 2016), black isn’t just appropriate — it’s therapeutic.

This isn’t just about what’s in your closet. It’s about what’s happening in your mind, your culture, and your highly curated depression-core Pinterest board.

Let’s take a deep, moody dive into why black is the one color that truly understands us right now.

🧠 PSYCHOLOGY: BLACK AS EMOTIONAL ARMOR

- Black isn’t just a shade — it’s a psychological security blanket for grown-ups.

- It projects confidence, control, mystery, and “please don’t speak to me in the elevator.”

- People wear black to feel strong, sleek, serious — and, let’s be honest, invisible on command.

- It’s also the color of introspection, which is great since everyone you know is either in therapy or pretending not to need it.

- In a world of oversharing, black is quiet power. It’s emotional minimalism. It’s saying, “I’m spiraling, but make it chic.”

🧬 ANTHROPOLOGY: BLACK AS SACRED, DEADLY, AND COOL FOR 6,000 YEARS

- Cultures around the world have long associated black with the spiritual, the powerful, and the forbidden.

- Ancient Egyptians saw black as the color of life-giving soil and rebirth — ironic, considering it now decorates all your funeral wear.

- In many African traditions, black symbolizes maturity, wisdom, and ancestral strength — not just a vibe, but a legacy.

- It’s been the color of priests, witches, rebels, punks, artists, and sometimes all five in one dinner party.

- Bottom line: black never belonged to one group. It’s a universal symbol of transformation and edge.

(Which makes sense, since the world is constantly transforming into a bigger mess.)

🧵 FASHION: BLACK IS A UNIFORM FOR HIGH FUNCTIONING DISASTER PEOPLE

- In fashion, black is the reset button — the one color that always works, even when nothing else in your life does.

- Coco Chanel gave us the Little Black Dress so we could go anywhere and look like we planned it. Even if we didn’t.

- Fashion loves black because:

- It’s elegant without trying.

- It slims everything, including your sense of impending doom.

- It doesn’t clash with anything except your feelings.

- From funeral director to runway model, black is the ultimate unifier.

- It also tells people, “I might cry in the bathroom later, but I’ll look good doing it.”

🔥 MODERN EXISTENTIAL CHAOS: BLACK MATCHES THE MOOD

- Look around. The world is:

- Overheated

- Overstimulated

- Overanalyzed

- And somehow still underfunded

- Colorful optimism is out. Dystopian monochrome is in.

- Black reflects the times. It’s the color of:

- Burnout

- Doomscrolling

- Climate despair

- And going to brunch pretending none of that is happening

- It doesn’t pretend everything’s okay. It says, “Yes, we are doomed, but I’ve accepted it and picked an outfit.”

🧃 BLACK VS OTHER COLORS: A COMPARISON (NO MERCY)

- White: Tries too hard to look innocent. Gets stained by feelings.

- Beige: Witness protection for the soul.

- Red: Screams for attention, like a toddler with a TikTok.

- Pastels: Great if you’re a cupcake or lying to yourself.

- Neon: Absolutely not. We’re too tired for that now.

- Black: Doesn’t beg. Doesn’t shout. Just exists with gravity.

Black doesn’t need to perform. It already won.

💅 THE REAL REASONS PEOPLE KEEP COMING BACK TO BLACK

- It’s easy. You don’t have to think. You just have to put it on and pretend you’re fine.

- It’s versatile: suitable for parties, protests, funerals, job interviews, and late-night existential spirals.

- It’s aspirational: people in black look like they read books and drink espresso without flinching.

- It’s unapologetic: black doesn’t try to make you feel better. It just makes you look like you already figured it out.

🪦 CONCLUSION: BLACK IS THE COLOR OF NOW. STILL.

- The world’s a mess.

- Hope is… intermittent.

- Reality feels like a series of increasingly absurd plot twists written by a tired intern.

- And in the middle of all this, black is the one color that says, “I know.”

Not “it’s going to be okay.” Just “I see what’s happening, and I dressed accordingly.”

So no, black isn’t a lack of imagination.

It’s the most honest choice we have.

🖤 TL;DR (Too Lost; Didn’t Reboot):

Black is:

- Your armor

- Your therapist

- Your shadow

- Your entire aesthetic

- The color of stylish surrender

- And somehow, still hope — just in a cooler jacket

Wear it like the world depends on it.

Because honestly? It might.

Cloud Dancer or Crowd Dodger?

ChatGPT:

🧼

Cloud Dancer

: Why Pantone’s Color of the Year Is White and That’s Somehow a Big Deal

So Pantone has announced its 2026 Color of the Year, and it’s not Barbie pink, post-apocalyptic green, or neon anything.

It’s Cloud Dancer, aka white, aka PANTONE 11-4201, aka “the color of surrender napkins and haunted yoga studios.”

On the surface, it’s peaceful. Clean. Aesthetic.

But in today’s chaotic, polarized, everything-is-an-argument world, picking white is like throwing a blank piece of paper into a bonfire and calling it diplomacy.

Let’s take a closer look at this “color” through the lenses of psychology, anthropology, fashion analysis, and general cultural exhaustion, with just the right amount of sarcasm to keep it fun.

🧠 PSYCHOLOGY: THE BLANK SLATE COMPLEX

- White represents calm, clarity, and peace — you know, all the things no one has felt since 2015.

- Psychologically, white is the absence of color, which in today’s hyperstimulated world, is weirdly provocative.

In a room where everyone’s yelling, silence is the loudest noise. - Pantone called it a “symbol of calming influence.” But isn’t that what they said about “Sand Dollar” in 2006? (It was beige. The world did not calm down.)

- White gives off major therapy appointment energy. The “I need a reset” shade for people whose lives are color-coded but still falling apart.

- It’s also the color of hospitals, minimalism, and people pretending to be fine via curated Instagram stories.

Summary: Pantone picked white because everyone’s tired, overstimulated, and probably in denial. So… nailed it?

🧬 ANTHROPOLOGY: WHITE IS NEVER JUST WHITE

- Culturally loaded? Absolutely. In the West, white = weddings, purity, Apple product packaging, and people with gluten allergies.

- In many Asian cultures, white = mourning, loss, and existential dread. (So, basically, still relevant.)

- Throughout history, white has been a color of privilege. Why? Because keeping anything white clean is a full-time job.

It’s the color of people who don’t sit on public benches. - White clothes have symbolized everything from spiritual elevation to colonial elitism to aggressive neutrality.

And yet Pantone described it as “a blank canvas.” Oh honey… there’s no such thing.

Summary: Picking white and calling it “neutral” is like putting mayonnaise on everything and calling yourself a chef.

🧵 FASHION ANALYSIS: WHITE IS A LUXURY ITEM DISGUISED AS SIMPLICITY

- White in fashion = rich people cosplay. Think: monochrome airport looks, goop-infused linen jumpsuits, and clothes that scream “I don’t sweat.”

- It’s not just a look, it’s a lifestyle of avoidance: avoiding dirt, effort, budget airlines, and barbecue sauce.

- Designers love white because it’s elevated, versatile, and mysterious, like someone who ghosted you and opened a skincare brand.

- In 2026, white feels like a trend for people who missed out on trends. The safe bet. The beige flag of fashion.

- Don’t get it twisted — wearing white in public is a power move, but only if you can afford to look like an unsullied marshmallow 12 hours later.

Summary: In fashion, white isn’t basic. It’s a subtle brag. Like saying “I have no stress” with a pressed white shirt and perfect teeth.

🔥 IN THE CULTURAL BONFIRE OF NOW, WHITE IS WEIRDLY LOUD

- In this era of everyone fighting about everything, white tries to play Switzerland. But that actually makes it suspicious.

- It’s the color of “I don’t want to pick sides,” which — let’s be real — is a side.

- In politics, social movements, and even pop culture, colors have meaning, and white is pretending it doesn’t.

- Cloud Dancer feels like a reaction to color fatigue — after years of neon, pink, and meme-core palettes, this feels like a detox.

Or a void. It’s hard to tell. - It might also be Pantone saying, “We’re scared of getting roasted online, so here’s a color nobody can complain about. Except… everyone still did.”

Summary: In a world of visual screaming, Pantone’s white is not peace — it’s avoidance dressed as enlightenment.

🍦 WHITE IS THE COTTAGE CHEESE OF COLORS (SORRY)

Let’s not forget what this color actually looks like in real life.

- Cloud Dancer is the color of:

- Cottage cheese

- Marshmallows left in the sun

- AirPods after two weeks in your gym bag

- Sad office walls

- The shirt you regret wearing to a spaghetti dinner

Summary: It’s not even a glamorous white. It’s “please pass the TUMS” white.

🏁 FINAL THOUGHT: THE COLOR OF SURRENDER OR THE COLOR OF RESET?

- White is being positioned as the color of renewal — a fresh start. But for most people, 2026 doesn’t look like a fresh start, it looks like a carry-over anxiety sequel.

- Choosing white isn’t just about fashion or aesthetics. It’s a mirror held up to a moment in history when everyone is overwhelmed, overexposed, and over it.

- So maybe Pantone’s choice is brilliant — not because it inspires, but because it reflects exactly how lost we are:

A society trying to start over, but too afraid to make a mark.

Final Summary: Cloud Dancer is not a color. It’s a mood. A vibe. A soft sigh of defeat in crisp linen.

Wear it if you dare. Just maybe don’t spill anything. Or say anything controversial. Or go outside.

Is Your Mind Just a Neural Accident?

ChatGPT:

The Emergent Mind: How Intelligence Arises — and Why That Might Not Be the Whole Story

🧠 What Is the Emergent Mind View?

- Intelligence arises not from individual neurons, but from interactions between vast networks of neurons.

- Similar principles underlie artificial neural networks (ANNs) in AI systems.

- Complex behaviors (e.g., decision-making, perception) emerge from simple interconnected units.

- Implication: Human cognition and AI systems may share deep structural similarities.

- Book: The Emergent Mind by McClelland & Suri proposes this framework as a bridge between brain science and machine intelligence.

✅ Strengths of the Emergent View

- Matches neuroscience evidence: distributed processing, plasticity, context-dependence.

- AI shows networked systems can learn, adapt, and simulate human-like behavior.

- Demystifies “mind”: no ghost needed, just interacting parts doing complex stuff.

⚠️ But… It’s Not the Whole Picture

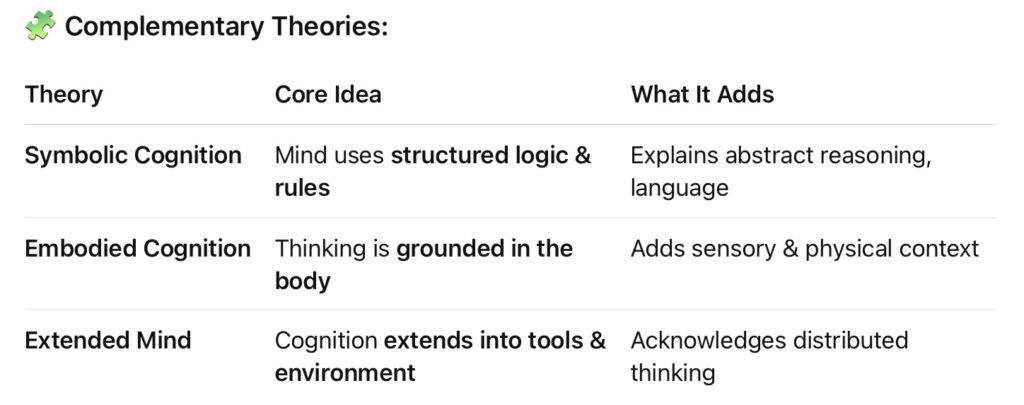

Let’s meet the three alternative theories that challenge or complicate this view:

⚙️ 1.

Symbolic Cognition

Brains as rule-based systems manipulating symbols like logic machines.

- Intelligence is about manipulating structured representations using formal rules.

- Language, math, planning require more than pattern matching — they need logic.

- Basis for early AI systems: expert systems, symbolic planning, rule-based models.

- Still used in explainable AI, formal reasoning, etc.

🔧 Critiques of Emergent View:

- Neural networks are weak at structured reasoning, especially with abstract or recursive tasks.

- Human thought includes deliberate logic and explainable steps, not just emergent behavior.

🧍♂️ 2.

Embodied Cognition

You don’t just think with your brain. You think with your whole awkward body.

- Intelligence arises from bodily interactions with the environment.

- Meaning comes from physical experience, not abstract representations.

- You understand “grasp” because you have hands that grasp.

- Roots in enactivism, sensorimotor theories, and developmental psychology.

🤖 In AI:

- Embodied agents, robotics, reinforcement learning in environments attempt to mirror this.

🔧 Critiques of Emergent View:

- ANN models often ignore bodily context, sensation, and motor grounding.

- Human cognition is deeply physical and emotional — not just statistical.

🌐 3.

Extended Mind

Your mind leaks out into your tools, apps, and browser tabs.

- Proposed by Clark & Chalmers (1998).

- Cognitive processes extend into the external world — notebooks, phones, maps, etc.

- You offload memory, logic, navigation to tools and systems you rely on.

- Cognition is distributed across brain, body, and environment.

🤖 In AI:

- Supports concepts like human-AI teaming, cognitive augmentation, and multi-agent systems.

🔧 Critiques of Emergent View:

- Neuron-based or ANN models ignore how much we rely on external systems to think.

- Where does the “mind” stop? It may not be bounded by the skull at all.

🎯 Takeaway Summary

But it’s just one piece of a larger, messier cognitive puzzle.

Emergent Mind theory explains a lot — especially how complex behavior can arise from simple neural units.

The Longevity Equation: Movement, Meaning, and Connection

ChatGPT:

🟦 Living Well to 100: Dick Van Dyke’s Rules, Science, and the Art of Staying Joyful

A practical and uplifting guide for all ages

1. A Life Lesson at 100: Why Dick Van Dyke Matters

- Few people reach 100 with the energy, humor, and lightness of Dick Van Dyke.

- In 100 Rules for Living to 100, he turns a century of experience into warm, funny, human “rules” — not rigid commandments, but mindsets for joyful longevity.

- The book reads like a conversation with a wise friend: stories from his childhood, his show-business career, late-life love, and reflections on staying vibrant even when the body ages.

- He reminds us: “I feel really good for 100.”

- Today’s geriatric science agrees with him: longevity is not only biology — it is behavior, mood, relationships, and purpose.

2. Rule #1 — Keep Moving: The Science of Active Aging

- Van Dyke still exercises three times a week, works out on circuits, and even dances.

- He says, “If I miss too many workouts, a stiffness starts creeping in.”

- Geriatric research confirms this:

- Regular movement (walking, stretching, light strength training) reduces fall risk, preserves muscle mass, supports balance, and improves cognitive function.

- Even 15–20 minutes daily is enough to trigger protective effects on the brain’s prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.

- Why it works: Movement stimulates blood flow, maintains joint lubrication, and keeps the body responsive — allowing older adults to remain independent and confident.

3. Rule #2 — Keep Playfulness Alive: Joy Is a Longevity Pill

- Van Dyke treats life as a “giant playground.” He still sings, jokes, dances, and pulls pranks.

- He famously said: “I never wake up in a bad mood.”

- Neuroscience shows that play reduces cortisol, improves immune function, and keeps neural networks flexible.

- Happiness and laughter also counteract inflammation, a major driver of aging.

- Why it works: A playful mind is an active mind — it prevents emotional rigidity and protects against depression, social withdrawal, and cognitive decline.

4. Rule #3 — Let Passion and Creativity Guide Your Days

- Van Dyke still performs, records music, and looks for new projects.

- “I’m one of those lucky people who got to do for a living what I would have done anyway.”

- Geriatric psychologists note that having a sense of purpose lowers mortality risk by up to 20–30%.

- Creative engagement strengthens frontal-lobe activity and preserves executive function.

- Why it works: Purpose gives you a reason to wake up, a reason to move, and a reason to stay mentally engaged.

5. Rule #4 — Love Is a Survival Skill, Not a Luxury

- Van Dyke openly credits love and companionship for his vitality.

- About his wife he said: “Our ongoing romance is the most important reason I have not withered into a hermetic grouch.”

- Loneliness is now recognized as a medical risk factor — comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

- Warm emotional bonds:

- reduce chronic inflammation

- protect cardiovascular health

- strengthen immune responses

- Why it works: Humans are social beings. Love and friendship light up the brain’s reward circuits and help stabilize mood, especially in later life.

6. Rule #5 — Let Go of Anger: Emotional Health Is Physical Health

- Van Dyke says, “Anger is one thing that eats up a person’s insides — and hate.”

- Long-term anger and resentment elevate cortisol, blood pressure, and inflammation, accelerating aging.

- Older adults who practice forgiveness and emotional regulation show better memory, stronger immune function, and lower rates of depression.

- Why it works: Emotional cleansing is part of biological maintenance. A calm inner life supports a healthy outer life.

7. Rule #6 — Stay Present: Don’t Live Only in Memory

- Van Dyke reflects: “I like to reminisce, but I don’t want to live there.”

- Dwelling excessively on the past can trap older adults in nostalgia loops that reduce curiosity and future-mindedness.

- Mindfulness research shows that staying present increases neural connectivity and reduces age-related rumination.

- Why it works: The brain stays sharp when it continues to anticipate, explore, and imagine new experiences.

8. Rule #7 — Accept Aging, Don’t Fear It

- “I don’t fear death… I’ve had such a wonderfully full and exciting life.”

- Acceptance reduces anxiety, improves life satisfaction, and aligns with higher well-being in older adults.

- Modern gerontology stresses positive aging: acknowledging limitations while celebrating capability.

- Why it works: Acceptance frees mental energy. It allows seniors to focus on joy, gratitude, and meaningful relationships.

9. What Dick Van Dyke Teaches Us — In the Language of Science and Story

- His life shows that longevity is a psychological achievement as much as a biological one.

- The most important ingredients are surprisingly simple:

- Move your body.

- Laugh every day.

- Keep your passions alive.

- Build and protect loving relationships.

- Avoid bitterness.

- Stay present.

- Accept your age with grace and humor.

- In his own words: “I feel really good for 100.”

- And the science agrees:

- Optimism correlates strongly with long life.

- Joy is medicine for inflammation.

- Social connection delays cognitive decline.

- Playfulness is mental exercise.

- Movement is the closest thing we have to a longevity fountain.

10. Final Message: A Gentle Blueprint for Living Well

- You don’t need fame, wealth, or perfect genetics.

- You need curiosity, joy, movement, love, gratitude — and a willingness to keep dancing even when the music changes.

- That’s not just Dick Van Dyke’s secret — it’s human biology’s secret too.

Civilization Is Glitching: Please Stand By

ChatGPT:

🧨 The New Malaise of Civilization:

When Words, Truth, and Reality Fall Apart

We’re living in an age where language is broken, truth is optional, and reality is… negotiable. It’s not just a feeling — it’s a diagnosable cultural condition. Philosophers warned us. Psychologists diagnosed us. Sociologists wrote entire shelves about it. But here we are — adrift in chaos, drowning in hashtags.

This is your user-friendly guide to understanding the new malaise of civilization — and how to stay (somewhat) sane in it.

⸻

🧠 1. Psychology: We’re All a Bit Unwell

• In 1930, Freud called modern society “neurotic”, burdened by repressed desires and mounting inner conflict.

• Today? It’s gone full psychotic: we no longer agree on what’s real, and that’s a textbook symptom.

• WHO reports 1 in 8 people globally now suffer from mental disorders. Anxiety and depression are booming like startup culture in 2011.

• Social media and AI now function as pseudo-therapists, influencers, and truth factories — often with tragic results.

• The line between real and imagined threats has blurred. That ping on your phone? Might be a meme. Might be an existential crisis.

💡 We are overwhelmed, overstimulated, and spiritually exhausted. That’s not weakness — it’s a rational response to irrational times.

⸻

🏛️ 2. Sociology: Society Is Breaking Its Own Rules

• Sociologist Émile Durkheim called it “anomie” — the breakdown of shared norms. Sound familiar?

• There’s been a collapse in social trust: appointments missed, promises broken, language used without meaning.

• Polarization has replaced conversation. We no longer talk with people — we talk at them, in tribal soundbites.

• Truth is now tribal: what you believe often depends on your political team, not evidence.

• Language has become a battlefield — especially online. Words are now weapons, used for manipulation, division, or attention.

💡 When we lose a shared understanding of meaning, communication fails. And without communication, society breaks down.

⸻

🤯 3. Philosophy: Truth Has Trust Issues

• Once upon a time, truth was noble. Now it’s seen as biased, relative, or obsolete.

• Philosopher Michel Foucault warned us: truth is power. Whoever controls the narrative controls the world.

• Today’s reality is shaped more by algorithms and outrage than facts or logic.

• Orwell’s warning from 1984 — “War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength” — now reads like Tuesday’s news.

• Philosopher Eva Illouz describes this as a “semantic collapse” — words no longer mean what they used to.

💡 The loss of shared truth isn’t just philosophical — it’s deeply political, and it’s affecting everything from law to love.

⸻

📺 4. Technology: Our Screens, Our Selves

• Sociologist Régis Debray says we’ve moved from the “graphosphere” (writing) to the “videosphere” (screens).

• Translation: deep reading and reflection have been replaced by short-form, hyper-emotional digital noise.

• Social media has amplified tribalism, curated echo chambers, and made disinformation scalable.

• You’re not just online. You’re being reshaped by what you scroll.

💡 The digital world didn’t just change what we see. It changed how we think — faster, louder, shallower.

⸻

💥 5. Symptoms of the Malaise

Let’s check your civilization’s vitals:

• 📈 Wars are increasing (61 global conflicts in 2024 — highest since 1946).

• 😵 Mental illness is surging.

• 🧹 Public discourse is collapsing — truth is whatever someone wants it to be.

• 😡 Rage has replaced reason, especially in politics and online life.

• 😶 Speech is devalued: everyone talks, but no one listens.

This isn’t just a cultural slump. It’s a full-on existential identity crisis.

⸻

🧘♂️ 6. So… What Can a Reasonably Decent Human Do?

Because screaming into the void isn’t a viable long-term strategy, here are a few practical survival tips:

✅ Curate your information diet:

• Choose a few reliable, fact-checked sources.

• Avoid doomscrolling and conspiracy rabbit holes.

• Understand the difference between news and noise.

✅ Build real relationships:

• Connect with people you can hug, not just DM.

• Practice empathy — it’s radical now.

• Disagree without dehumanizing.

✅ Set boundaries with tech:

• Log off. Go outside. Touch literal grass.

• Protect your attention like it’s your bank account.

• Don’t argue with strangers in comment sections. It’s never worth it.

✅ Reconnect with reality:

• Read books. Listen to music. Cook something.

• Practice mindfulness, not mindlessness.

• Live offline long enough to remember what that feels like.

✅ Be decent, even when no one’s watching:

• Keep your word. Say thank you. Tip well.

• Choose humility over cynicism.

• Lead with curiosity, not certainty.

💡 You don’t have to fix the world. Just don’t become part of the problem.

⸻

🌱 7. Is There Hope?

Actually… yes.

• History shows us that crisis often precedes progress. Think Hegelian dialectic: tension → conflict → transformation.

• Today’s chaos may be the ugly labor pains of a new era — one where truth, dialogue, and empathy are rebuilt from the rubble.

• But that future won’t be delivered by an app. It starts in classrooms, conversations, quiet moments, and you.

💡 You don’t need to change the world. You just need to show up for it — with clarity, kindness, and conviction.

⸻

✍️ Final Word

Yes, we’re in a moment of profound disorientation — where words are twisted, truth is corrupted, and reality is optional. But civilization has collapsed before, and spoiler alert: we’re still here.

So don’t give in to numbness or noise. Be the person who speaks honestly, listens carefully, thinks critically, and shows up with heart.

That alone is rebellion enough.

Predicting the Beat: Music, Time, and Human Nature

ChatGPT:

The Poetry of Prediction: Musical Time, Rhythm, and Groove – Milton Mermikides

This lecture explores how rhythm in music transforms our perception of time, linking human cognition, physical movement, and social behavior. It emphasizes how rhythm functions as a predictive structure, aligning with biological and social patterns to produce pleasure, cohesion, and expressive potential.

⸻

🎵 Conclusion:

Professor Milton Mermikides unveils rhythm as both a temporal scaffold and a tool of prediction that humans evolved to interpret the world. Musical rhythm operates across hierarchical time layers, from microtiming to large-scale structures, guiding emotional and physical responses. Human brains naturally construct expectational frameworks, responding with joy or surprise when rhythms confirm or violate predictions. The lecture spans from primal coordination (tribal drumming, work songs) to complex rhythmic devices like displacement and grouping dissonance. It closes by recognizing modern technology’s ability to emulate and expand rhythmic complexity beyond human capacity, yet still intelligible to listeners. Rhythm is revealed as an emotional, cognitive, and communal language binding human experience through time.

⸻

🧠 Key Points:

🎯 Musical Time: Music unfolds in time, not space, demanding real-time engagement and structured listening.

🧬 Biological Sync: Rhythmic ranges align with heart rates, stride frequencies, and memory capacity, anchoring rhythm in physiology.

🧑🤝🧑 Coordination through Rhythm: Societies use rhythm for labor, bonding, and survival—e.g., water drumming, sea shanties, work songs.

🧠 Prediction Engine: The brain constantly builds rhythm-based frameworks to predict sonic events, releasing dopamine when correct.

🕰️ Pulse to Polyrhythm: From simple pulses to complex subdivisions (tactus, tatum, meter), rhythm reflects nested temporal structures.

🎭 Displacement Dissonance: Rhythmic tension arises when strong beats are omitted or shifted—e.g., syncopation, backbeats.

🧮 Grouping Dissonance: Rhythms like the tresillo (3-3-2) challenge binary meter, enriching musical expression across cultures.

🧑🎤 Microtiming: Subtle timing shifts, especially in jazz (e.g., swing feel), convey expression even within milliseconds.

🧰 Euclidean Rhythms: Widely found across cultures, these divide time “fairly” across beats—e.g., Flamenco, West African bell patterns.

🤖 Human-Machine Coevolution: Digital tools (DAWs, sequencers) now replicate and enhance human rhythmic nuance, creating a new expressive frontier.

⸻

📚 Summary:

1. Time as Canvas: Unlike visual arts, music unfolds in a strict temporal sequence. The audible spectrum, spanning 20Hz to 20kHz, defines what we hear, while rhythm defines when events occur—rooted in ranges from milliseconds to minutes.

2. Sound-Movement Evolution: Human cognition evolved to link movement with sound. Rhythmic sounds aid coordination, alertness, and social bonding, exemplified by cultural practices like Bayaka water drumming and prison work songs.

3. Predictive Listening: The brain anticipates rhythmic events, forming internal grids. A beat or pulse becomes the default window for attention, optimizing energy use and enhancing enjoyment when predictions are met or artfully violated.

4. Rhythmic Hierarchies: Music layers time into pulse (tactus), subdivisions (tatum), meter, and hypermeter. Multiple frameworks operate simultaneously, allowing music to “speak” in complex nested timescales.

5. Binary Bias: Humans tend to impose a binary structure onto rhythms. EEG studies show the “tick-tock” effect even when hearing uniform beats—explaining 2/4 and 4/4’s dominance in music worldwide.

6. Delight in Surprise: Pleasure peaks when rhythmic prediction is mildly violated, as shown by the inverted-U graph of syncopation. Artists use metric shifts and syncopation (e.g., Nirvana, Stravinsky, Mozart) to create emotional tension.

7. Grouping Tensions: Tresillo patterns (3-3-2) create grouping dissonance against binary meters. Used globally, they extend into double and triple forms (e.g., Radiohead’s “Weird Fishes”), producing satisfying clashes.

8. Maximally Fair Rhythms: Euclidean rhythms, distributing hits evenly across time, appear in numerous global traditions, from Bulgarian dance to jazz. Bartók notated them using additive meters.

9. Microtiming Feel: Jazz swing isn’t rigid—it’s a continuum. Nina Simone’s “My Baby Just Cares for Me” maintains a consistent off-grid swing within ~50ms. Microtiming is expressive and perceptible below conscious awareness.

10. Technology’s Rhythm Revolution: Machines now replicate human rhythm’s expressive detail. Composers like Steve Reich and Frank Zappa explore rhythms beyond human ability, blurring human-machine musical boundaries.

Lungs: Life’s Hidden Power

ChatGPT:

Breath Taking: The Power, Fragility, and Future of Our Extraordinary Lungs

Introduction

The human lungs are extraordinary organs—essential, intricate, and profoundly vulnerable. In Breath Taking, pulmonologist Michael J. Stephen presents a deeply informed and impassioned account of the lungs’ biological complexity and their critical role in public health. Drawing from his experience as a physician and researcher, Stephen explores how environmental, social, and medical factors threaten lung health, and he urges a rethinking of public policies to protect this vital organ.

⸻

The Anatomy and Function of the Lungs

Marvels of Biology

Lungs are composed of over 300 million alveoli, each contributing to a surface area akin to a tennis court. This structure enables them to exchange gases rapidly and efficiently. Every minute, they interact with thousands of liters of air, absorbing oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide—a process crucial to life itself.

The Immune Role

Far from being passive, the lungs are active participants in immune defense. They trap airborne pathogens and pollutants using mucus and cilia, and trigger complex immune responses that prevent infections from taking root.

⸻

Vulnerabilities of the Respiratory System

Premature Birth and Neonatal Care

Babies born prematurely often have underdeveloped lungs, lacking surfactant—a substance crucial for lung expansion. Advances in neonatal medicine, including surfactant replacement therapy and modern ventilators, have drastically improved survival rates.

Chronic Diseases

Stephen highlights chronic respiratory illnesses such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cystic fibrosis (CF). He discusses both their biological basis and how they reflect broader social inequities, from exposure to pollutants to disparities in healthcare access.

⸻

The Scourge of Smoking

A Preventable Epidemic

Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable lung disease and death. Despite decades of public health campaigns, smoking continues to thrive, fueled by aggressive marketing—especially in low-income and developing regions.

Big Tobacco’s Legacy

Stephen critically examines the tobacco industry’s decades-long misinformation campaign, drawing parallels with current threats like vaping, which now poses new dangers to lung health, especially among youth.

⸻

Environmental Threats and Pollution

Air Quality and Global Disparities

Air pollution—from vehicle emissions, industrial waste, and natural disasters like wildfires—contributes to millions of deaths annually. Vulnerable communities bear the brunt, often living near factories or highways with poor air regulation.

Microparticles and Lung Penetration

The author details how tiny particles can lodge deep in the lungs and enter the bloodstream, contributing not just to respiratory issues but also to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurological disorders.

⸻

The COVID-19 Wake-Up Call

A Global Lung Crisis

The coronavirus pandemic placed lungs at the center of a global health emergency. Patients suffering from COVID-19-induced pneumonia and ARDS (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome) overwhelmed healthcare systems.

ECMO and Critical Care

Stephen shares stories from the frontline, including the use of ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation) for patients whose lungs had failed. These tales emphasize both the fragility and the resilience of human lungs under extreme duress.

⸻

Breakthroughs in Treatment

Gene Therapy and Cystic Fibrosis

New treatments for CF—once considered a childhood death sentence—are transforming lives. Drugs that correct protein misfolding or enhance lung function have extended lifespans and improved quality of life dramatically.

Personalized Medicine

Stephen underscores the rise of precision medicine in pulmonology, including therapies tailored to genetic profiles and environmental exposures. This marks a shift toward prevention and targeted intervention.

⸻

Health Inequities and Systemic Failures

Racism and Respiratory Health

Black Americans and other minorities suffer higher rates of asthma, lung cancer, and COVID-19 mortality. These outcomes are tied to environmental racism, unequal access to care, and historic discrimination in housing and industry.

Healthcare Access

Universal lung health remains elusive in a system plagued by cost barriers, geographic disparities, and lack of preventive focus. Stephen calls for systemic reform to ensure that all people have access to air, diagnosis, and treatment.

⸻

Clean Air as a Human Right

Policy and Advocacy

Stephen argues that clean air must be treated as a public good and a human right. He critiques weak environmental policies and urges stronger enforcement of pollution controls, green infrastructure investment, and international cooperation.

A Call to Action

From banning harmful emissions to ending the tobacco epidemic, Stephen’s final chapters are a plea for action. He encourages citizens, healthcare providers, and policymakers to rethink lung health as central to public well-being.

⸻

Conclusion

Breath Taking is more than a medical book—it is a manifesto for change. Michael J. Stephen blends science, storytelling, and advocacy to illuminate the essential role of the lungs and the urgent need to protect them. He reminds us that in every breath we take, we depend on a system both miraculous and vulnerable—and that safeguarding our lungs means safeguarding life itself.

FAQs

What is the central theme of

Breath Taking

by Michael J. Stephen?

The book explores the biology, vulnerabilities, and significance of the human lungs, weaving together scientific insights, personal stories, and public health concerns to argue for stronger protection of respiratory health.

How does the book describe the structure and function of the lungs?

It highlights that lungs contain over 300 million alveoli, providing a large surface area for efficient gas exchange. The lungs also play roles in immune defense and regulating body chemistry.

Why are lungs considered fragile organs?

Lungs are constantly exposed to the external environment through every breath, making them vulnerable to infections, pollutants, and toxins.

What role do lungs play in the immune system?

They act as a frontline barrier by trapping pathogens and initiating immune responses, helping prevent respiratory infections.

What diseases affecting the lungs are covered in the book?

The book discusses asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, pneumonia, and COVID-19, among others.

How does pollution affect lung health?

Airborne pollutants can enter deep into the lungs, causing inflammation, increasing the risk of chronic disease, and contributing to premature death.

What is the significance of cystic fibrosis in the book?

Cystic fibrosis is highlighted as a condition where recent gene therapy has led to significant improvements in lifespan and lung function, showcasing medical advancement.

What is the book’s stance on smoking and tobacco?

Stephen criticizes the tobacco industry and smoking’s continued prevalence, citing it as the leading preventable cause of lung disease.

How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence the book’s narrative?

It brought global attention to lung vulnerability, highlighting the need for ventilators, critical care, and better preparedness for respiratory crises.

What does the book reveal about healthcare inequality?

It shows how marginalized communities face higher risks of lung disease due to poor air quality, systemic racism, and lack of access to healthcare.

What solutions does the author propose to protect lung health?

The book calls for clean air legislation, reduced pollution, smoking cessation programs, equitable healthcare access, and recognizing clean air as a human right.

How are premature babies’ lung issues addressed?

The book explains the use of surfactant therapy and ventilators in neonatal intensive care units, which have greatly improved outcomes for premature infants.

What is ECMO and why is it mentioned?

ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation) is a life-saving technology used in severe lung failure cases, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What message does the book send about environmental justice?

It emphasizes that air quality and lung health are disproportionately worse in communities of color and low-income areas due to systemic neglect.

How does

Breath Taking

blend science with storytelling?

The book mixes clear medical explanations with emotional patient narratives, making complex pulmonary issues accessible and human-centered.

Your Brain on Pause: Why Doing Nothing Matters

ChatGPT:

Here’s your delightful 800-word bullet-point essay, suitable for the general public—complete with science, sarcasm-free clarity, and just enough brain drama to keep it interesting. You’re welcome. Or, you know, default-mode welcomed.

🧠 The Default Mode Network (DMN):

What It Is, Why It Matters, and How Your TikTok Addiction Is Ruining It

🔍 What Is the Default Mode Network (DMN)?

- The Default Mode Network is a group of interconnected brain regions that becomes active when your mind is not focused on the outside world.

- It was discovered by accident—scientists noticed certain areas of the brain lit up during rest, when people weren’t doing any tasks.

- In short, it’s the “mental idle mode” your brain switches to when you’re:

- Daydreaming

- Remembering the past

- Imagining the future

- Reflecting on yourself

- Just… staring into space (with purpose!)

🧬 Why Do We Have a DMN?

(From an Evolutionary Biology Perspective)

- Survival isn’t just reacting—it’s planning. The DMN likely evolved to help humans think ahead, recall, and simulate scenarios before acting.

- It lets us mentally rehearse:

- “What will happen if I go there?”

- “What happened last time I tried this?”

- “What will that person think if I say this?”

- This mental time-travel helps with:

- Avoiding danger

- Social bonding

- Planning for future events (like winters, weddings, or war)

- The DMN gave early humans a reflective advantage—a kind of built-in simulation engine for trying out ideas without needing to test them in real life (where mistakes can be fatal).

🧠 The DMN According to Neuroscience

- The DMN is made up of brain regions like the:

- Medial prefrontal cortex (self-evaluation)

- Posterior cingulate cortex (memory and awareness)

- Precuneus (imagination and perspective)

- These regions help process:

- Your personal narrative (“Who am I?”)

- Moral reasoning

- Understanding others’ thoughts (“What is she thinking about me?”)

- It operates best when:

- You’re not doing anything in particular

- You’re internally focused

- You’re allowed to just think

📱 How Doomscrolling Wrecks the DMN

Doomscrolling = the compulsive consumption of endless bad news, tragic updates, and algorithmic despair via social media.

- Interrupts Resting State:

- Every time you scroll, your attention snaps to something new—disrupting the calm, steady activity of the DMN.

- Floods Your Brain with External Stimuli:

- The DMN is inward-focused. Doomscrolling constantly forces it outward—to war headlines, celebrity scandals, and passive-aggressive posts from people you haven’t seen in years.

- Hijacks Your Inner Narrative:

- The DMN builds your sense of self and your personal story. Doomscrolling introduces fear, hopelessness, and constant comparison—altering that narrative in unhealthy ways.

- Increases Anxiety and Rumination:

- Ironically, doomscrolling both suppresses healthy DMN activity (while you’re actively scrolling) and fuels negative DMN processing (once you stop and start overthinking what you saw).

- Trains the Brain to Avoid Stillness:

- If you’re constantly distracted, your DMN doesn’t get to practice reflection. You become less able to just sit and think—a key human skill.

🎶 How Music Affects the DMN

(Spoiler: it’s better than Twitter)

- Activates DMN—if the music is passive and emotional:

- Slow, nostalgic, ambient, or instrumental music encourages mind-wandering, which helps fire up the DMN.

- Enhances Memory and Emotion:

- Music can trigger autobiographical memories, activating the DMN’s key regions related to self-reflection.

- Promotes Deep Thinking and Imagination:

- Listening to emotionally rich music without lyrics allows the mind to drift, stimulating DMN activity and even creative insight.

- Reduces Stress and Supports Mental Health:

- Unlike doomscrolling, music lowers cortisol and helps your brain re-enter a resting reflective state.

- Caveat: Not all music works:

- Fast, lyric-heavy, or complex music that demands attention shifts the brain out of DMN mode and into task-related processing.

🧠 TL;DR — Wrap-Up: Why You Should Care About Your DMN

✅ What to Do With This Knowledge

- Be aware of your mental habits. Your DMN needs downtime to function well.

- Take breaks from screens. Stop feeding your brain a constant firehose of information.

- Listen to reflective music. It’s basically a warm bath for your brain’s introspective systems.

- Let yourself daydream. That’s not being lazy—that’s your brain doing internal housekeeping.

Your Default Mode Network isn’t some useless background process—it’s the core of your reflective human experience. Take care of it like it’s the Wi-Fi router of your soul.

Go ahead. Close the tab.

Put your phone down.

Put on some Teresa Teng.

Stare out the window.

Let your brain come home.

The Fear Factory: Why Panic is in Your Genes (and Your Gut)

Gemini:

Why Do We Fear? The Biology of Our Most Primal Emotion