Evolved Minds in a Designed World: How Evolutionary Thinking Shapes Modern Life and AI

ChatGPT:

🧬 Evolution: The Old Science That Still Runs Your Life (and Your Phone)

So, you think evolution is just about dinosaurs, Darwin, and finches with very specific beak drama?

Think again, my undercooked hominid friend. Evolution isn’t just ancient biology—it’s a full-blown operating system for your brain, your choices, your relationships, and yes, even your AI overlords.

Let’s break it down in a way your tribal instincts can handle: bullet points.

🧓 The OG Evolution Crew: Big Brains, Big Problems

Charles Darwin

– a.k.a. the Original Bearded Biologist

- Came up with natural selection—the idea that traits helping organisms survive get passed on.

- Avoided saying “humans evolved too” in On the Origin of Species because he was scared of upsetting his wife (and all of Victorian England).

- Basically said, “Life evolves. Deal with it.”

Francis Galton

– talented… then very problematic

- Discovered regression to the mean (e.g., kids of tall parents are usually less tall, not NBA-ready).

- Then invented eugenics, which aged as well as milk in a volcano.

- TL;DR: smart guy, terrible ethics. Moving on.

R.A. Fisher

– father of statistics, awkward dinner guest

- Gave us ANOVA (stats nerds cheer!) and tried to mathify sex ratios and peacock tails.

- Said some wildly racist stuff that has since been debunked—by his own statistical methods.

- Evolutionary karma is real.

William Hamilton

– the kindness math guy

- Invented Hamilton’s Rule:

It’s worth helping someone if the genetic payoff is high enough.

C < B x r → Cost < Benefit × Relatedness - So yes, your brother helped you move because evolution told him to. (And maybe because you bribed him with pizza.)

🧠 Human Behavior: Ancient Brain, Modern Mess

Your brain is stone-age hardware trying to operate in a WiFi world. This is called an evolutionary mismatch, and it explains a lot:

Craving Sugar Like a Trash Panda?

- Ancestors: “Sugar = rare = eat all of it now!”

- You: “I just ate 14 cookies in a Target parking lot.”

- Solution: Don’t trust your hunger. It’s a prehistoric scam.

Fear of Public Speaking?

- Ancestral tribes: “If I say something dumb, I’ll get exiled and eaten by hyenas.”

- You: “I’m doing a PowerPoint and sweating through my blazer.”

- Relax. Nobody’s going to feed you to anything. Probably.

Addicted to Social Media?

- Your brain: “Tribal status! Am I liked? Am I seen? Do I belong?”

- Instagram: “Here’s a curated nightmare that hacks your approval-seeking instincts.”

- Try: Logging off before the algorithm eats your soul.

🧬 Everyday Evolutionary Thinking: How to Outsmart Your Inner Caveman

Use evolution like a tool, not just trivia:

- 🛒 Shop smart: Don’t grocery shop hungry. Evolution made you hoard food like a starving squirrel.

- 🧘 Fight stress with movement: Cortisol = “Run from predator.” Use that energy or it turns into rage-crying at emails.

- 🛌 Sleep like a caveperson: Low light, no screens, regular hours. Your body still thinks the moon is your bedtime cue.

- ❤️ Relationships: Understand jealousy, bonding, and mate choices as evolutionary leftovers. Don’t let your lizard brain pick your soulmate.

- 🧬 Health: Don’t misuse antibiotics—bacteria evolve fast. Treat medicine like a war, not a buffet.

🤖 Evolution in AI: Digital Darwinism Is Here

Now for the fun part: robots are evolving too.

AI engineers have borrowed evolution’s homework and turned it into algorithms. It’s called genetic algorithms, and it’s real, it’s weird, and it works.

How it works (like natural selection, but with code):

- 🧪 Generate random solutions (DNA)

- ⚔️ Test them (fitness)

- 🧬 Keep the best ones (survival of the fittest)

- 🔁 Mix them and mutate them (crossover + mutation)

- Repeat until something smart emerges (or terrifying)

Real Examples of Evolutionary AI:

- 🚀 NASA Antenna Design:

- Used genetic algorithms to evolve a weird, squiggly antenna that worked better than anything humans designed.

- Evolution said: “Trust the chaos.”

- 🎮 Game AI Opponents:

- NPCs evolve strategies to counter human players.

- Translation: Your enemies are learning. Good luck.

- 🏎️ Self-Driving Cars (Simulations):

- Cars learn how to drive by crashing 9,000 times in simulation and evolving not to.

- It’s digital natural selection, minus the whiplash.

- 🧠 Neural Network Design:

- AI helps design other AI brains using evolutionary principles.

- Yes, this is the beginning of the singularity. Thank you for asking.

Why This Matters:

- Evolution isn’t just about old fossils and textbook diagrams.

- It’s a powerful lens for solving modern problems—from medicine to mental health to artificial intelligence.

- And it explains why you still fear spiders but not car insurance forms. (Even though one is more statistically dangerous. Guess which.)

🧠 TL;DR: Evolution Is Everywhere

- Your behavior? Shaped by genes trying to survive in a world that no longer exists.

- Your relationships? Semi-functional gene alliances.

- Your bad habits? Perfectly reasonable… 10,000 years ago.

- Your AI? It’s learning the same way life did: fail, mutate, repeat.

So next time you eat six donuts while doomscrolling and yelling at Alexa, just remember:

It’s not you. It’s your evolutionary baggage.

Also, yes—AI is using evolution better than you are. Time to catch up.

The Attention Thief Is in Your Hand

ChatGPT:

🎯 Attention Is All You Need — Especially Now

An Informative and Occasionally Sarcastic Essay for Smart Seniors Who Are Accidentally Letting the Internet Eat Their Brain

🔍 1. Start Here: “Protect your attention like it’s your retirement fund”

- Imagine your attention is money.

Every moment you spend watching or reading something is like spending a dollar. - Spend wisely, and your mental health, energy, and joy compound like interest.

- Waste it on garbage, and it evaporates like crypto in a windstorm.

- You wouldn’t hand your retirement savings to a stranger in sunglasses selling NFTs out of a van.

So why hand your attention to TikTok’s algorithm, which is basically the same thing, but with worse music?

📱 2. The Digital Casino: Why Social Media Is So Addictive

- TikTok, Threads, Instagram — they weren’t built to “connect people.”

They were built to keep you staring at a screen for as long as possible, so they can sell ads. - These apps use slot-machine psychology. Every swipe is a mystery. Will it be funny? Shocking? Political rage-bait? A cat that can drive? You don’t know — and that’s the point.

- This is called “variable reward.” Casinos use it. So do pigeons in Skinner boxes.

And now… you.

🧠 3. What Happens to Your Brain?

- Your attention system gets hijacked.

The brain learns to expect quick rewards, avoid depth, and stay hyper-reactive. - It messes with:

- Memory (you forget what you just saw 5 minutes ago)

- Sleep (blue light + anxiety = brain soup)

- Mood (short-term dopamine spikes → long-term emptiness)

- Focus (you start reading articles like this in bullet points only… oh wait)

- For older adults, this can accelerate cognitive decline, increase loneliness, and lower overall life satisfaction.

- Translation: If you doomscroll every day, you’re paying top dollar to feel confused, tired, and vaguely irritated.

🛡 4. How to Protect Your Attention

Think of attention like a precious resource — like coffee in the apocalypse or your last piece of pie.

Protect it by:

- Setting limits: 30 minutes of screen time for pure nonsense. Use a timer.

- Filtering content: Not everything that trends is worth your time.

Ask: “Will I remember this next week?” - Avoiding rabbit holes: You clicked one video about back pain, and now your feed thinks you’re a 300-year-old mystic with 17 conspiracy theories. Walk away.

- Choosing high-quality input: Listen to a good podcast. Read something that doesn’t blink at you. Revisit a documentary with an actual narrator, not a dancing voiceover AI.

🤖 5. Wait—Wasn’t “Attention Is All You Need” About AI?

Yes!

In 2017, AI researchers wrote a now-famous paper titled “Attention Is All You Need.”

It introduced a technology called the Transformer, which powers modern AI models (including the one writing this).

- The paper’s idea:

AI doesn’t need to look at all information equally. It should focus attention on the parts that matter. - That simple insight made AI better at understanding, predicting, and writing language.

So yes — attention changed everything for AI.

🧘 6. But It’s Even More Important for Humans

Here’s the twist:

- AI got smarter by learning how to allocate attention.

- Humans are getting dumber by letting algorithms do the allocating for them.

Oops.

- Your attention shapes what you remember, what you feel, and even who you become.

- If you spend all your time watching rage-inducing talking heads or 5-second cake fails, your brain gets trained to expect chaos, novelty, and instant reward.

- But if you focus your attention on ideas, art, real conversations, and learning…

You build depth, resilience, and clarity.

🧾 7. So What Should You Actually Do?

- ✅ Choose content with care. (No more feeding your brain digital corn syrup.)

- ✅ Take mental breaks. Silence is a luxury.

- ✅ Spend more time with one good idea than 50 bad ones.

- ✅ Challenge yourself. Read things that stretch your thinking, not just affirm your beliefs.

- ✅ Write, reflect, talk to people who are alive and not avatars.

- ✅ Be curious — but don’t outsource your curiosity to an algorithm.

🧠 Final Thought:

AI got smarter when it learned to focus.

So can you.

And unlike AI, you’ve got something extra:

- A lifetime of wisdom

- A sense of humor

- And the ability to know when something’s worth your attention — and when it’s just glittery junk

Your time is precious.

Your attention is priceless.

Spend both like you mean it.

The Algorithm of the Sky: Kepler’s Method Unveiled

ChatGPT:

⭐

Johannes Kepler: The Astronomer Who Computed the Universe Before Computers Existed.

⭐

Part I — Kepler’s Life and Achievements: A Brief Introduction

- Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, and visionary thinker who forever changed how we understand the heavens.

- Living at a time before telescopes were widely used, before calculus was invented, and long before the laws of physics were formulated, Kepler still managed to uncover the true mathematical structure of the solar system.

- Working with enormous dedication, fragile health, financial insecurity, and the chaos of the Thirty Years’ War, Kepler displayed an intellectual courage matched by very few in history.

- He inherited Tycho Brahe’s extremely precise naked-eye observations—vast tables of planetary positions measured over 20 years—and used them as the foundation of his work.

- Kepler’s approach was radically new: he didn’t just describe where planets were; he wanted to know why they moved the way they did. He was one of the first people in history to imagine that celestial motion followed physical laws, not divine whims or ancient geometric ideals.

- From this combination of patience, imagination, and mathematical skill, Kepler produced three of the most important discoveries in the history of science:

⭐

Kepler’s First Law (1609): Planets move in ellipses, not circles.

- For 2,000 years, astronomers believed planetary orbits must be perfect circles.

- Kepler shattered this ancient idea by showing that ellipses fit the data far better than circles.

- This was a bold break with tradition and one of the earliest victories of data over ideology.

⭐

Kepler’s Second Law (1609): Planets sweep out equal areas in equal times.

- This law revealed that planets speed up when closer to the sun and slow down when farther away.

- It showed that the Sun is not a passive lamp but the master regulator of planetary motion.

⭐

Kepler’s Third Law (1619): The square of a planet’s period is proportional to the cube of its distance.

- This “Harmony of the Worlds” is a stunning universal pattern linking every planet in the solar system.

- Centuries later, Newton proved Kepler’s Third Law arises naturally from gravity.

- Today it is still used to calculate the orbits of planets, moons, asteroids, space probes, and even exoplanets.

- In addition to astronomy, Kepler made breakthroughs in:

- Optics (explained how vision works and how lenses form images)

- Mathematics (early ideas related to calculus and integration)

- Physics (proposed that a physical “force” from the Sun drives planetary motion)

- Scientific method (demanded that models match observations exactly—no “fudging”)

- In short, Kepler is the man who turned astronomy from guesswork and geometry into a science of laws and data.

⭐

Part II — How Kepler’s Methods Anticipated Modern Computing (in Plain English)

Kepler lived 400 years before computers, but his working style reads like someone writing algorithms by hand.

Below is how he effectively acted as a human computer, using methods that look remarkably like modern numerical analysis, simulation sciences, and data-driven modeling.

⭐

1. He used “brute-force” calculation — like a computer running loops.

- Kepler tested countless orbital shapes for Mars: circles, ovals, stretched circles, off-center circles.

- For each model he:

- calculated predicted positions

- compared them to Tycho Brahe’s observations

- adjusted parameters and tried again

- This is exactly how computers solve problems today:

Run → Compare → Adjust → Repeat - Kepler did thousands of these steps by hand.

⭐

2. He let data override theory — just like modern evidence-based computing.

- For centuries astronomers assumed heavenly motion must be perfectly circular.

- Kepler found an 8-arcminute discrepancy—tiny but real—between the circular model and Mars’s position.

- Instead of ignoring it, he treated the error as absolute proof that the model was wrong.

- His rule was:

“If even one measurement disagrees, the theory must change.” - Today, this principle underlies all data science, AI training, and statistical modeling.

⭐

3. He used early versions of “numerical integration.”

- Kepler’s Second Law (equal areas in equal times) is normally solved using calculus.

- But calculus didn’t exist yet.

- So Kepler:

- broke the orbit into tiny slices

- calculated each slice’s area

- added them together to find the planet’s speed

- This is exactly how computers perform:

integration, differential equations, and orbital simulations. - Kepler essentially hand-computed what NASA’s software does now.

⭐

4. He searched parameter space — like modern optimization algorithms.

- He constantly adjusted:

- orbital eccentricity

- shape of the ellipse

- position of the sun

- timing of motion

- And kept retesting.

- This is the ancestor of:

- gradient descent

- model fitting

- machine-learning parameter tuning

- least-squares regression

⭐

5. He built and compared hypothetical universes — early simulation modeling.

- Kepler didn’t just compute Earth’s or Mars’s real orbit.

- He computed alternative universes:

- what if gravity worked differently?

- what if distance controlled speed in a different ratio?

- what if orbits were circular… or oval… or elliptical?

- He “ran” these universes in his imagination and his notebook.

- This is the logic of today’s:

- climate simulations

- cosmological simulations

- orbital models

- computational physics

⭐

6. He used visualization — graphs before graphing existed.

- He drew diagrams showing:

- triangles between Earth, Mars, and Sun

- area sweeps

- geometric distortions in predicted paths

- These served as early data visualizations, similar to:

- scatter plots

- parametric curves

- analytic diagrams used in physics software today.

⭐

7. He believed nature follows simple, elegant rules — guiding principle of modern algorithms.

- Kepler searched for mathematical harmony:

“Nature uses as little as possible of anything.” - This is the same philosophy behind:

- elegant algorithms

- clean models

- efficient code

- Occam’s razor in machine learning

⭐

Conclusion: The First Great Human Computer

- Kepler did not have a telescope.

- He did not have calculus.

- He did not have algebraic tools, modern notation, or any computing machinery.

- But he had:

- Tycho’s precise data,

- a relentless insistence on accuracy, and

- a mind that worked algorithmically.

Kepler discovered the laws of planetary motion by doing what computers do today: testing models, minimizing errors, running simulations, visualizing patterns, and seeking elegant mathematical truths.

In a real sense, Kepler didn’t just revolutionize astronomy — he pioneered the computational way of thinking that defines modern science.

Beyond the Heliosphere: The Twin Probes That Redefined Our Edge

ChatGPT:

🌌 VOYAGER 1 & 2: A COSMIC JOURNEY BEYOND THE SUN

1. Origins: How Two Small Spacecraft Became Humanity’s Farthest Explorers

- In 1977, NASA launched Voyager 2 (August 20) and Voyager 1 (September 5) to take advantage of a once-in-176-years planetary alignment.

- Primary mission:

- Fly past Jupiter and Saturn

- Voyager 2: continue to Uranus and Neptune

- Perform detailed imaging, measure magnetic fields, atmospheres, radiation belts

- Both spacecraft vastly exceeded expectations—successful flybys, historic photographs, and decades of continuous science.

- After completing planetary exploration, they transitioned into their Interstellar Mission: studying the boundary of the Sun’s influence and beyond.

2. Science Tools: How They “See,” “Hear,” and “Feel” Space

Even today, despite limited power, each Voyager carries instruments that still work:

Magnetometer (MAG)

- Measures the strength and direction of magnetic fields.

- Helps determine:

- the shape of the heliosphere

- the “texture” of interstellar magnetic fields

- turbulence beyond the Sun’s boundary

- Acts like an ultra-sensitive, 3-D “cosmic compass.”

Plasma Wave Subsystem (PWS)

- Listens to oscillations of electrons in plasma.

- Detects “ringing” caused by solar storms hitting the interstellar medium.

- Lets scientists calculate plasma density, even though Voyager 1 cannot measure speed directly.

Other instruments

(some now off)

- Cosmic ray detectors

- Low-energy charged particle sensors

- Planetary imaging cameras (now shut down)

- Plasma detectors (Voyager 1’s stopped in 1980; Voyager 2’s operated until 2024)

3. Major Discoveries: What They Found in the Outer Solar System

Jupiter (1979)

- First close images of the Great Red Spot’s swirling structures

- Discovery of volcanic Io, the most geologically active body in the Solar System

- Europa’s cracked ice shell hinting at a subsurface ocean

Saturn (1980–81)

- Exquisite details of Saturn’s rings

- Titan’s thick atmosphere (Voyager 1 skipped Uranus/Neptune specifically to study Titan)

Uranus & Neptune (Voyager 2 only)

- Uranus: sideways rotation, strange magnetic field

- Neptune: supersonic winds, Great Dark Spot, geysering moon Triton

These planetary flybys revolutionized planetary science.

4. The Heliosphere and the Interstellar Frontier

After leaving the planets, the Voyagers entered the Sun’s outermost region:

Solar wind → termination shock → heliosheath → heliopause

- Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause in 2012

- Voyager 2 in 2018

- They became the first human-made objects in interstellar space.

What they discovered there

- The boundary is not sharp—it’s a tangled, complex transition zone.

- Magnetic fields did not rotate dramatically as expected, revealing a “braided” boundary.

- Plasma density suddenly increased by ~100×, proving they’d entered the interstellar medium.

- Solar storms still reach them from 15–20 billion km away, creating ripples that PWS “hears” as rising tones.

- Interstellar space is not empty—it has turbulence, magnetic waves, and density variations on surprisingly small scales.

5. How Voyager 1 “Hears” the Galaxy

- Solar shock waves compress interstellar plasma.

- Compressed plasma makes electrons oscillate at a frequency tied only to density.

- PWS records these frequencies, which scientists convert into sound-like spectrograms.

- The result is the famous “sound of interstellar space” — a rising whistle that marks Voyager’s entry into denser regions.

6. Distance and Direction: Where Are They Now?

- Voyager 1: ~24 billion km from Earth, traveling north of the ecliptic.

- Voyager 2: ~20 billion km, traveling south of the ecliptic.

- Both move at ~15–17 km/s, forever leaving the Sun behind.

- In ~40,000 years:

- Voyager 1 passes 1.7 light-years from star AC+79 3888

- Voyager 2 passes near Ross 248

They will not enter any planetary system closely—space is too vast.

7. Their Final Stages: When Power Finally Fades

Gradual Shutdown

- RTGs lose ~4 watts per year.

- By early–mid 2030s, science instruments will shut down one by one.

- Eventually the transmitters will no longer produce enough power for a radio signal.

After power loss

- Electronics freeze, orientation drifts, antennas stop pointing at Earth.

- Temperature slowly falls toward cosmic background (~3–10 K).

- They become dark, silent, frozen artifacts drifting between the stars.

How long do they last?

- Micrometeorite erosion is extremely slow—millions to billions of years.

- Golden Records (engraved aluminum covers + gold-plated copper discs) likely survive >1 billion years.

8. Galactic Future: Their Journey Through the Milky Way

- They remain gravitationally bound to the Galaxy, not flying into intergalactic space.

- They orbit the Milky Way once every 230 million years, like the Sun.

- Over millions–billions of years, they drift far from our solar system—thousands of light-years away—joining the galaxy’s quiet population of dust, rock, and wandering debris.

- Unless captured by a star or hit by something rare, they will outlast Earth, the Sun, and possibly our civilization.

In the end…

Voyager 1 and 2 are tiny emissaries carrying human fingerprints, still whispering data from a realm no spacecraft has ever reached. Long after their power dies, they will continue their silent journey—two cold, eternal messengers crossing the galaxy, carrying greetings from Earth into the deep future.

The Mind, Unmuted

ChatGPT:

The Quiet Voice in Your Head — And the Machines Learning to Hear It

Why new brain-computer interface research is astonishing scientists, worrying ethicists, and reshaping the future of communication.

⸻

For decades, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have carried a kind of sci-fi mystique: the possibility that one day a machine might let paralyzed individuals “speak” through thought alone. Until recently, though, even the most advanced BCIs relied on something surprisingly ordinary—effort. Users still had to try to move their lips or tongue, producing faint but decodable motor signals.

But a new study published in Cell pushes the frontier dramatically forward. It suggests that BCIs can now pick up inner speech—the silent voice we hear only in our minds—and turn it into intelligible words. The advance is thrilling for people who cannot speak. It is also, as several researchers put it, “a little unsettling.”

Below is what the breakthrough really means, why it matters, and what it absolutely does not herald.

⸻

1. The Breakthrough: Inner Speech Is Not as Private as We Thought

• Inner speech—silent self-talk, imagined dialogue, mental rehearsal—produces real, measurable activity in the motor cortex, the same region that controls the physical mechanics of speaking.

• The new study shows that this activity is structured, consistent, and decodable—not a jumble of random thoughts.

• With the help of modern AI, specifically deep-learning models tuned to detect delicate neural patterns, researchers achieved up to 74% accuracy decoding sentences from imagined speech.

In simpler terms: the whisper you hear inside your mind creates a faint echo in your speech-planning circuits, and AI can now hear that echo.

⸻

2. How It Works: Not Mind-Reading, But Pattern Recognition

• BCIs use tiny implanted electrodes—each smaller than a pea—to record electrical activity from neurons involved in speech.

• These signals are fed into AI models trained on phonemes, the basic units of sound.

• AI acts as a translator: turning motor patterns into phonemes, phonemes into words, and finally smoothing everything into coherent sentences.

The process is less “telepathy” than speech-to-text with a biological microphone.

Importantly, the system works only when the user:

• has an implanted BCI

• goes through extensive calibration

• focuses on cooperative tasks

Random daydreams, emotional states, memories, and abstract thoughts remain well outside the machine’s reach.

⸻

3. Why This Matters: Speed, Comfort, and Freedom

For people who can no longer speak due to ALS, stroke, or spinal cord injury, attempted speech can be exhausting. Inner-speech decoding:

• requires far less physical strain

• is much faster

• feels more natural—closer to the way able-bodied people form thoughts before speaking

This is why scientists say it could restore fluent conversation rather than laborious, letter-by-letter communication.

Inner-speech BCIs are, in a word, compassionate. They give a voice back to people who have lost theirs.

⸻

4. The Uneasy Side: Thoughts That Leak

And yet, the very thing that makes inner speech so powerful—the fact that it resembles attempted speech—introduces an ethical dilemma.

Participants sometimes produced decodable neural signals without intending to communicate, such as:

• silently rehearsing a phone number

• imagining directions

• mentally repeating a word

• thinking through a response before deciding to speak

This raises a simple but profound question:

If your inner monologue produces a neural footprint, could a machine capture it even when you don’t want it to?

The researchers tackled this directly.

⸻

5. The Solutions: Mental Passwords and Neural Filters

Two protections showed promise.

A. Training BCIs to Ignore Inner Speech

The system can be tuned to respond only to attempted speech—strong, intentional signals.

Downside: this eliminates the speed advantage that imagined speech provides.

B. A “Wake Word” for the Brain

Much like how Alexa waits for “Hey Alexa,” the BCI can be trained to activate only when a user imagines a specific phrase—

something rare and unmistakable, such as:

“Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.”

Think of it as a password you speak only in your mind.

This solution worked remarkably well and allowed users to keep inner thoughts private unless they deliberately chose to “unlock” the device.

⸻

6. What This Technology Cannot Do

To prevent misunderstandings, here is what this research does not demonstrate:

• BCIs cannot read spontaneous thoughts.

• They cannot access memories.

• They cannot decode emotions or images.

• They cannot read minds from outside the skull with a consumer device.

• They cannot work without surgery and consent.

The decoding is highly structured, not magical. It works because speech planning is predictable, not because every private thought is suddenly an open book.

⸻

7. Why Ethicists Are Paying Attention

Neuroscientists see this work as a logical next step.

AI researchers see it as a technical triumph.

Ethicists, however, see a warning.

The biggest concern is not today’s medical implants but tomorrow’s consumer BCIs:

• EEG headbands

• Neural earbuds

• VR-integrated neural sensors

These devices cannot read inner speech today. But the new study hints that one day, with enough resolution and AI sophistication, parts of our thinking could become legible.

As Duke philosopher Nita Farahany says,

we are entering an era of brain transparency—a frontier that demands new mental-privacy laws and stronger user protections.

⸻

8. The Bottom Line: A Breakthrough Worth Celebrating—With Eyes Open

This research is a milestone.

It may eventually allow paralyzed people to communicate at the speed of thought.

It restores autonomy.

It restores dignity.

It restores connection.

But it also marks the moment society must confront a new question:

What parts of the mind should remain private?

The technology is astonishing.

The responsibility it brings is even greater.

From 15 Hours to 996: The Dream That Clocked Out

ChatGPT:

🧠

From Keynes to 996: How We Fumbled the Future and What to Do About It

An essay in bullets, because paragraphs are for people who aren’t already burned out.

📜 I. Keynes: The Grandfather of Unrealistic Hope

- In 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes wrote an essay with the painfully optimistic title:

“Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.”

Spoiler: we are the grandchildren. - His central thesis?

Thanks to technological progress and compound interest (sexy stuff), humans would eventually solve the economic problem.

Translation: we’d produce so much wealth that people wouldn’t need to work much. - He predicted:

- We’d work 15 hours a week

- The economy would grow 4 to 8 times larger

- Humans would finally be free to pursue beauty, truth, love, and probably interpretive dance

- He did not predict:

- Burnout

- Slack

- Hustle culture influencers named “Blayze”

💼 II. What We Got Instead: 996 and the Myth of the Hustle

- 996: A soul-grinding work schedule where people labor from 9am to 9pm, 6 days a week.

It sounds like a factory setting, because it is. Only now the factory is your MacBook. - Born in China’s hypercompetitive tech sector, 996 became the ultimate flex in Silicon Valley:

“If you’re not bleeding out of your eyeballs for your startup, do you even believe in innovation?” - Why did we embrace this instead of Keynes’ 15-hour brunch-and-meditation fantasy?

Reasons We Work Like Caffeinated Hamsters:

- Relative needs > Absolute needs

Once you’ve got food and a roof, you start wanting a standing desk, a Peloton, and a house plant that’s also a tax write-off. - Capitalism doesn’t stop when you’re full.

It invents new hungers. Suddenly, you need an app that delivers pre-peeled oranges. - Technology didn’t free us—it tagged us like wildlife.

You can now work from anywhere… which just means you work everywhere. - Fear. Just raw, unfiltered economic anxiety.

Job security is a myth, benefits are a dream, and AI is always one bad performance review away from replacing you with a spreadsheet.

- Relative needs > Absolute needs

🤯 III. Congratulations, You’re in Late-Stage Capitalism

- Keynes thought the “economic problem” would eventually be solved.

He didn’t account for:

- Billionaires hoarding GDP like Pokémon cards

- Housing prices ascending like they’re trying to reach heaven

- Productivity gains being funneled into CEO bonuses and surveillance software

- Instead of liberation, we got:

- Productivity trackers that count your keystrokes

- Bosses who say “we’re a family” right before laying off 200 people via Zoom

- Self-care guides that recommend waking up earlier to “carve out time for joy”

- We didn’t get post-scarcity.

We got post-dignity, but hey—at least we have mobile banking.

🛟 IV. Realistic, Not-Too-Painful Ways to Survive the Mess

🔧 Recalibrate Success

- You don’t have to win capitalism.

- Success = enough money, tolerable job, ability to nap without guilt.

- Celebrate mediocrity in a world obsessed with hustle.

💻 Extract Resources from the System, Then Nap

- Learn a high-leverage skill that lets you work less, not more.

- Use capitalism like it uses you. (Poorly, but with confidence.)

- Automate your savings. Pay yourself first. Pretend you’re a benevolent CEO of your own life.

🧠 Mental Health is Resistance

- Say “no” more often.

Practice in the mirror if you must:

“No, I will not attend a brainstorming session at 7pm.” - Quit the Cult of Productivity.

You are not a machine. You are a tired squirrel with a calendar app.

🤝 Build a Micro-Community

- Find 3–5 people who:

- Make you laugh

- Don’t try to sell you NFTs

- Will split a Costco membership with you

- Community makes crisis survivable.

Also, Costco churros.

🧪 Embrace Weird Joy

- Take up hobbies that don’t scale.

- Bake bread badly. Paint frogs. Sing off-key.

- Joy doesn’t have to be monetizable. In fact, it shouldn’t be.

🚨 Adjust Expectations

- Keynes was wrong, but not useless. He was imagining what could be.

- Take the dream. Modify it.

- Maybe not 15-hour work weeks. But how about a job that doesn’t ruin your back and soul? That’s… something.

🎤 Conclusion: We Are the Grandchildren, and We Are Tired

Keynes dreamed of a world where we’d be free to sing, stroll, and contemplate life.

Instead, we got team-building Zoom calls and a $6 oat milk latte we can’t afford.

But there’s still hope. Not in utopia. Not in Elon Musk. But in the tiny, defiant act of living like a human in a world designed for machines.

You’re not doomed. You’re just deeply scheduled.

So breathe. Opt out (where you can). And don’t forget—

Sometimes surviving is the revolution.

We’ve Survived Steam Engines, ATMs, and Outsourcing — But Can We Survive ChatGPT?

ChatGPT:

📉📈

Humans vs. Machines: A (Mostly) Friendly Struggle for Employment

A Bullet-Point History of Work, Worry, and Why You Should Still Learn Plumbing

🏛️ Once Upon a Time: The Industrial Revolution and Its Dirty Little Steam-Powered Secrets

- In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Industrial Revolution dragged us out of the fields and into the factories.

- Machines began replacing biceps with levers, sparking fears of mass job loss. (Spoiler: they weren’t entirely wrong — but also not entirely right.)

- The Luddites famously smashed weaving machines in protest, proving once again that people hate change unless it’s in their couch cushions.

Bottom line: Yes, machines replaced jobs — but they also created new ones. Hello, factory supervisors. Goodbye, sheep-shearers.

🏭 Then Factories Got Fancy: Enter the 20th Century

- Technological progress continued, but instead of just replacing muscle work, it started automating repetitive tasks in manufacturing.

- Assembly lines and early automation made productivity soar and reduced the need for humans to do boring stuff like tighten bolts all day.

- But people found new work: driving trucks, running offices, filling out forms, yelling at interns.

Lesson here? Humans moved up the food chain — from doing the work to organizing it, managing it, or talking about it on conference calls that should’ve been emails.

🧠 The Knowledge Economy: Computers Giveth, and Also Taketh Away

- Starting in the 1970s–1980s, computers rolled into workplaces like glitter at a toddler’s birthday — spreading everywhere and refusing to leave.

- This kicked off what economists call Skill-Biased Technological Change (SBTC):

- Technology made skilled workers more productive (and rich-ish).

- Less-skilled workers? Not so much.

- Office workers who knew how to use Excel were suddenly indispensable. Workers who didn’t? Suddenly dispensable.

Translation: Computers didn’t destroy all jobs — they reallocated opportunity based on who could speak “Microsoft Office” fluently.

🤖 Enter AI: The Robot With a LinkedIn Account

- Today’s AI is not your grandma’s machine. It’s not just replacing muscle or memory — it’s gunning for middle-class brain work too.

- AI systems (like me, hi) now handle:

- Writing emails,

- Analyzing data,

- Diagnosing illnesses,

- Creating art,

- And sometimes pretending to be better at poetry than they actually are.

Big vibe shift: This isn’t just “skill-biased” anymore. It’s task-biased — if your job includes repetitive, predictable tasks, AI wants it. Regardless of whether you wear a hard hat or a tweed blazer.

💼 But Wait, There’s History! And Hope. (Sort Of.)

- Let’s rewind to some very smart (and very nervous) economists:

- John Maynard Keynes warned about “technological unemployment” back in the 1930s — fearing machines would replace workers faster than we could invent new jobs.

- In the 1980s, Wassily Leontief said, “What the combustion engine did to horses, AI will do to us.”

- Horses never made a comeback. They got replaced. Fully. 100%. Sad horse emoji.

- But unlike horses, humans are sneaky. They adapt. They learn new tasks. They invent jobs like:

- Social media manager,

- TikTok influencer,

- AI prompt engineer (a fancy way to say “person who tells the robot what to do”).

Point being: So far, humans have survived every wave of tech, mostly by moving sideways into tasks that haven’t been automated… yet.

🧩 AI and the Modern Worker: Who’s Safe, Who’s Sweating?

- AI is eating the middle of the labor market:

- Entry-level white collar jobs? Under threat.

- Legal research, data crunching, even basic code-writing? Totally GPT-able.

- But guess who’s doing fine?

- Plumbers, electricians, caregivers, therapists, teachers — jobs that are physically, emotionally, or contextually complex.

- Creative professionals with taste and judgment — because AI can generate content, but it can’t decide what’s cool (yet).

- People who know how to use AI well — not just build it, but guide it, prompt it, and translate its outputs into human usefulness.

New motto: If you can’t beat AI, learn to boss it around.

🛠️ So What Should You Learn Now, Instead of Crying Into Your Resume?

🚫 Jobs AI Can’t Easily Do:

- Therapy (talking to a robot about your childhood is not ideal).

- Teaching and mentoring.

- Skilled trades (robots still suck at drywall).

- Complex decision-making involving real humans.

- Taste-making, judgment, vibes, leadership. (Yes, “vibes” are an economic advantage now.)

✅ Jobs That Use AI to Look Way Smarter Than You Are:

- Prompt engineer (actual job title now).

- Automation consultant (aka “person who Googled how to use Zapier”).

- Creative director using AI tools for fast output.

- Analyst who uses AI to produce 10x more charts than a normal human.

📚 Final Thoughts: From Pies to ATMs to Radiologists

- Economists talk about the “changing pie” — not just that the economy grows, but that what’s in it changes.

- 300 years ago: farms.

- 200 years ago: factories.

- Today: offices, platforms, gig work, vibe-checking content calendars.

- AI might shrink some slices, but it’ll bake new ones:

- Jobs we haven’t imagined yet.

- Tasks that emerge from new industries.

- Work centered on being human in ways machines can’t (or at least, shouldn’t).

In the war between technology and jobs, humans haven’t lost — they’ve just had to reinvent themselves repeatedly. And now, in the age of AI? Time to reinvent again. Preferably before your chatbot boss schedules your next Zoom meeting.

💌 TL;DR for the Skimmers:

- AI is real. It’s powerful. It’s here to mess with your job.

- Don’t panic. History suggests we adapt.

- Learn to do what AI can’t (emotion, judgment, context).

- Or use AI so well that no one notices you’ve been working 3 hours a week.

And if all else fails?

Become a plumber. Seriously. They’re recession-proof and robot-proof.

Boltzmann Brains: Statistically Cursed

ChatGPT:

🧠

Boltzmann Brains: An Informative Descent into Cosmic Absurdity

⚙️

What Is a Boltzmann Brain?

- A Boltzmann brain is a hypothetical self-aware entity that arises due to random fluctuations in a high-entropy universe.

In simpler terms:

Imagine a fully-formed brain—with fake memories, emotions, and regrets—suddenly appearing out of nowhere, floating in space, and thinking it’s late for a meeting. - It’s not the result of evolution, biology, or hard work. It’s a cosmic accident—like if someone sneezed and a laptop appeared.

- These brains would have:

- A functional consciousness,

- Illusory memories of a past that never happened,

- No physical body (probably),

- And no real environment. Just the illusion of one, courtesy of random quantum chaos.

- Why is this weird?

Because you might be one.

Yes, you. The person reading this with your “real life” and your “childhood” and your “Netflix queue.”

All potentially fake.

You’re welcome.

🧪

The Origins: Boltzmann and the Thermodynamic Mess

- The idea is named after Ludwig Boltzmann, a 19th-century physicist who worked on entropy—a fancy word for “the universe’s obsession with messiness.”

- Boltzmann’s work showed that:

- Systems naturally go from order to disorder over time.

- But, given infinite time, tiny pockets of order can spontaneously emerge due to random fluctuations.

- Boltzmann proposed this to explain why our universe is relatively ordered (low entropy) despite the Second Law of Thermodynamics trying to make everything fall apart.

- He hypothetically suggested that maybe our entire universe is just a rare, low-entropy fluctuation in an otherwise chaotic, high-entropy cosmos.

And cosmologists, never ones to resist an existential spiral, ran with it.

🧨

Why Did It Blow Up Again in 2002?

- Around 2002, cosmologists started noticing something uncomfortable:

In many popular cosmological theories (especially ones involving eternal inflation or infinite time), Boltzmann brains are statistically more likely to exist than real, evolved beings. - Why? Because:

- Creating a single, self-aware brain from random particles is easier (in terms of entropy) than creating a whole functioning universe full of stars, planets, and people.

- So if you assume randomness and infinite time, the math suggests there should be vastly more Boltzmann brains than real humans.

- This leads to an extremely awkward question:

If Boltzmann brains are more common than real observers, how do we know we’re not one of them? - And if we are, then:

- All of science, history, and your Spotify Wrapped is just a hallucination.

- This essay may not exist.

- And we’re basically living in the universe’s most low-budget simulation.

🧮

Why Cosmologists Take It (Uncomfortably) Seriously

- Scientists don’t believe in Boltzmann brains because they want to. They believe in questioning models that predict absurd results. Like:

- If your universe model creates more hallucinating brains than evolved ones…

- It might be broken. Like, deep-fried-beyond-recognition broken.

- Boltzmann brains are now used as a sanity test for cosmological models:

- If your theory ends up with a universe full of delusional brains floating in heat death… it’s probably wrong.

- The goal is to make models where normal observers like us are more probable than the rogue space brains.

- In this sense, Boltzmann brains are like cosmology’s version of a red flashing warning light that says:

“This theory may be statistically cursed. Proceed with regret.”

🌌

Multiverse Theories and the Measure Problem: It Gets Worse

- Enter the multiverse: the idea that our universe is just one bubble in an infinite foam of other universes.

- When you apply Boltzmann brain logic to multiverse theories, things get apocalyptic:

- Now you’ve got infinite space and infinite time to spawn random minds.

- Meaning: even more Boltzmann brains than you can mentally process. An entire multiverse of delusional floaty brains.

- This leads to the measure problem:

- How do you calculate probabilities in an infinite universe?

- If everything happens somewhere, what does “likely” even mean?

- If 99.999999% of observers are Boltzmann brains, does that make you one? Is this sentence fake? Am I fake?

🔚

Final Thoughts: Why It Matters (and Why It’s Hilarious)

- The Boltzmann brain paradox forces scientists to rethink the foundations of their theories:

- How do we define an “observer”?

- Can we trust our memories?

- How do we avoid models that end in absurd conclusions?

- In a weird way, Boltzmann brains do a great job of keeping cosmology grounded.

Because any theory that predicts you’re not real probably needs a tune-up. - And honestly? The idea that random brains float into existence and hallucinate entire fake lives is:

- Terrifying,

- Mathematically sound (ugh),

- And exactly the kind of philosophical nightmare you’d expect from a universe that gave us dark energy and pineapple on pizza.

🧠 TL;DR:

Boltzmann brains are what happen when physicists try to explain entropy, get too honest about probability, and accidentally create a thought experiment that makes you question your existence while eating cereal.

Welcome to cosmology.

Where even the brains are unstable.

From Sun to Cesium: How We Learned to Count Time Precisely

ChatGPT:

⏱ The Evolving Second: How Humanity Redefined Time Itself

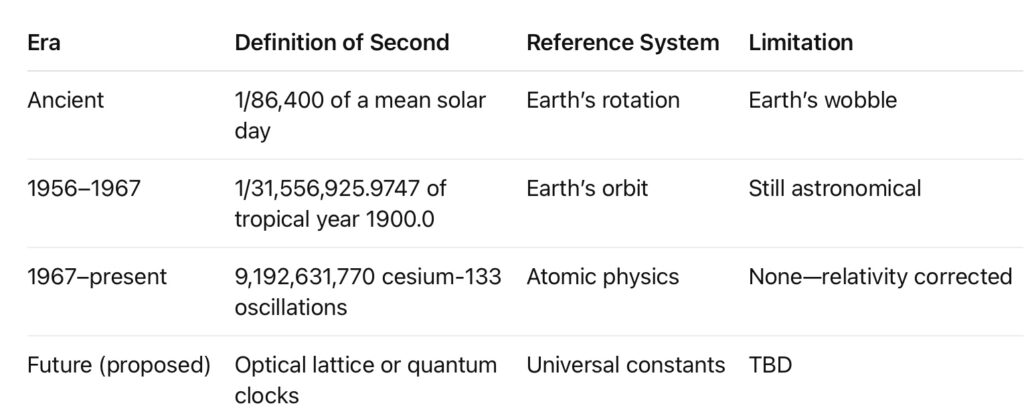

1.

Before We Had Clocks — Time as Nature’s Rhythm

- For most of human history, “time” meant sunrise, noon, and sunset.

- A “day” was one full spin of the Earth, and everything else was guesswork: shadows, sundials, water clocks, and candle marks.

- There was no standard “second.” Time was local, natural, and messy — people just lived by light and dark.

2.

The Birth of the Second (Pre-1960): Earth as the Clock

- As mechanical clocks improved, scientists needed a smaller, universal slice of the day.

- They divided one mean solar day into:

- 24 hours,

- 60 minutes per hour,

- 60 seconds per minute.

- This made 1 second = 1/86,400 of a day.

- In theory, that seemed elegant — but in practice, the Earth isn’t a perfect timekeeper:

- Its rotation wobbles due to tides, earthquakes, shifting ice, and interactions with the Moon.

- Astronomers in the 1930s and 1940s noticed that the Earth’s spin wasn’t uniform.

- The “day” could vary by milliseconds — enough to throw off precision navigation and astronomy.

- Lesson learned: the planet is a wonderful home, but a terrible metronome.

3.

The First Fix: Measuring Time by the Sun’s Orbit (1956–1967)

- Scientists tried to anchor the second to something more stable than Earth’s rotation: the Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

- In 1956, the second was redefined as:

1/31,556,925.9747 of the tropical year 1900.0

(the length of one full seasonal cycle as measured at the start of the 20th century) - This was still astronomical, but less wobbly — orbital motion is smoother than daily spin.

- However, it still depended on Earth’s movement, and astronomers wanted something universal, measurable anywhere in the cosmos.

4.

The Atomic Revolution (Post-1967): Time by Quantum Physics

- The breakthrough came from atomic physics.

- Every atom of cesium-133 vibrates at a precise frequency when it flips between two energy states (a “hyperfine transition”).

- These vibrations are identical everywhere in the universe — perfect for defining time.

- In 1967, the International System of Units (SI) adopted this definition:

One second is the duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation emitted by a cesium-133 atom transitioning between two hyperfine levels. - Why this matters:

- No dependence on the Earth, Sun, or any celestial body.

- Immune to weather, geography, and political borders.

- Identical whether you’re in Paris, on Mars, or in interstellar space.

- Humanity’s clock was no longer tied to spinning rocks — it was tied to the fundamental physics of the universe.

5.

Precision Meets Relativity: The Second Isn’t Always Equal Everywhere

- The atomic second is absolute by definition — but time itself is relative.

- According to Einstein’s theories:

- Special relativity → A moving clock ticks slower relative to a stationary one.

- General relativity → A clock in stronger gravity ticks slower than one in weaker gravity.

- So, even though both use cesium, two clocks in different environments disagree on how many seconds have passed.

- Examples:

- A clock at sea level runs slightly slower than one on top of Mount Everest (gravity weaker at altitude).

- GPS satellites orbit higher up, where gravity is weaker, so their clocks tick faster — but they’re also moving fast, which slows them down. Engineers compensate for both effects every day.

- Astronauts aboard the International Space Station experience both effects — net result: their clocks run about 10 microseconds per day slower than Earth’s.

6.

The Second Beyond Earth: Space and Time in Deep Space

- Far from Earth, the same cesium rule applies — but relativistic corrections are critical.

- Voyager 1 and 2, now billions of kilometers away, have clocks that tick at slightly different rates:

- Their speed (~17 km/s) slows their clocks by about 0.05 seconds per year relative to Earth (special relativity).

- Being far from the Sun’s gravity speeds them up by roughly the same amount (general relativity).

- The effects nearly cancel out, but NASA tracks both precisely through signal analysis and software corrections.

- All deep-space missions synchronize their signals to Earth’s atomic time, converting everything into a unified “solar system time” (Barycentric Dynamical Time).

- The spacecraft’s clocks don’t change — our mathematics adjusts for physics.

7.

Time on Other Worlds: Mars and Beyond

- A day on Mars (a sol) is 24 h 39 m 35 s — about 39½ minutes longer than an Earth day.

- Colonists will likely use Mars Coordinated Time (MTC) for civil life, defining “noon” by the Sun overhead just like Earth days.

- Physically, Mars clocks tick slightly faster than Earth clocks:

- Gravity is weaker (0.38 g) and Mars is farther from the Sun.

- The result is roughly 0.34 milliseconds faster per Earth day.

- Over a decade, that adds up to about 1.25 seconds ahead of Earth.

- Software would automatically adjust for these effects in communications, navigation, and finance between planets.

- For humans on Mars, the difference is unnoticeable — but for engineers, it’s vital.

8.

Why the Redefinition Matters

- Each redefinition of the second reflects our evolving understanding of physics and precision:

- From observing the sky → to measuring orbital motion → to using atomic transitions.

- The shift represents our journey from macroscopic time (celestial motion) to microscopic time (quantum physics).

- Today’s atomic clocks are so stable that they’d drift less than a second over the age of the universe.

- Future redefinitions may tie the second to even more fundamental constants, like the vibrations of optical transitions or quantum entanglement.

9.

In One Sentence

Humanity began counting time by watching the sky — but ended up counting it by listening to atoms.

10.

Key Takeaway Table

Final Thought:

From sundials to cesium atoms, each step in redefining the second marks a triumph of understanding — a move from watching nature to mastering nature’s constants. The second today is not just a unit of time; it’s a symbol of humanity’s precision in measuring the universe itself.

Don’t Learn AI. Outsmart It.

ChatGPT:

🛠️

The Developer Survival Handbook: AI Edition

“Don’t Just Learn AI — Learn to Wield It Better Than the People Trying to Replace You.”

A field guide for software engineers in the age of robots, restructuring, and resume rewrites.

📖 Table of Contents

- Welcome to the Post-Human Coding Era

- Why “Learning AI” Isn’t Enough

- The Three Kinds of Developers (and Who Gets Replaced)

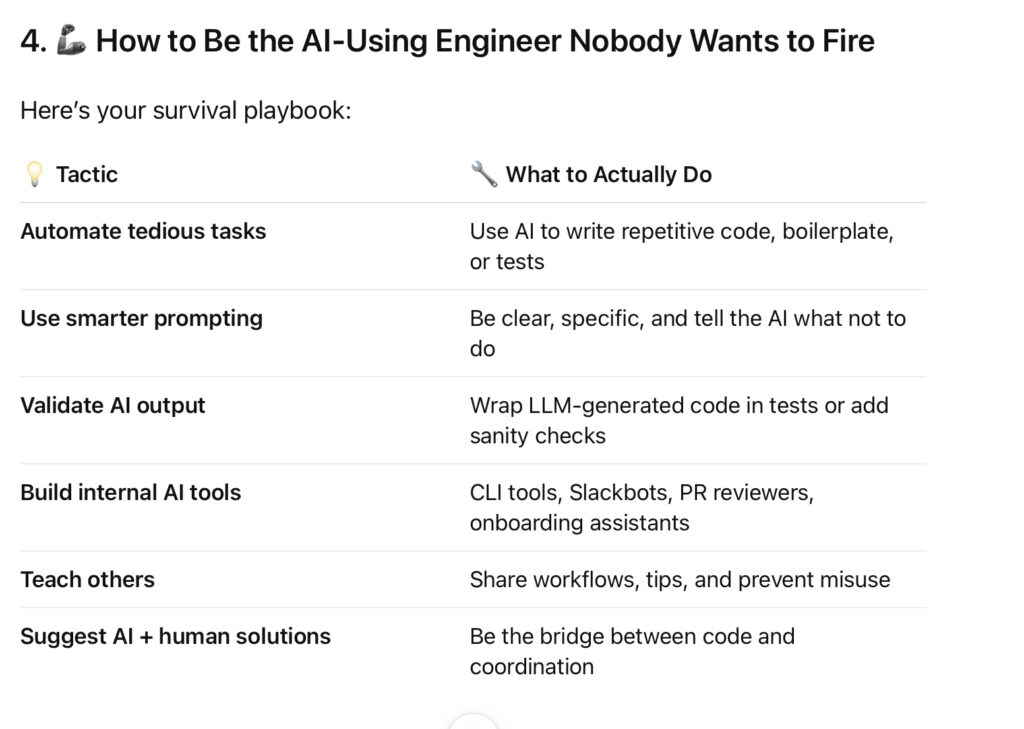

- How to Be the AI-Using Engineer Nobody Wants to Fire

- Tools, Tactics & Prompts

- The Developer’s Prayer to the Debugging Gods

- Final Notes from the Future

1. 💼 Welcome to the Post-Human Coding Era

Congratulations. You’re a software engineer in the most unstable version of the tech industry since the Great Jira Rebellion of 2018.

- LLMs are writing code

- Execs are laying people off by the hundreds

- And HR is holding “AI Enablement” meetings while quietly updating the severance letter template

Here’s the truth:

LLMs aren’t replacing you. But the people using LLMs better than you? They might.

2. 🤖 Why “Learning AI” Isn’t Enough

You’ve heard the advice:

“You should learn AI to stay relevant.”

But here’s what they don’t say:

- Everyone is learning AI now

- Most people don’t know how to actually use it effectively

- Simply knowing what “transformers” are won’t save your job

The real move?

Become the person who uses AI better than the people trying to automate you.

3. 🧠 The Three Kinds of Developers (and Who Gets Replaced)

🥱 The Passive Learner

- Watches AI videos

- Adds “AI-curious” to LinkedIn

- Still waits 45 minutes for npm install

- 🚫 Most likely to be automated

🛠️ The AI Tinkerer

- Uses LLMs to generate tests, docstrings, or bash scripts

- Writes custom prompts for recurring problems

- Builds little helpers in the corner of the codebase

- ✅ Keeps their job and doubles productivity

🧙♂️ The Workflow Sorcerer

- Reorganizes workflows to be AI-first

- Builds internal tooling with LLM APIs

- Speaks prompt as a second language

- 👑 Gets promoted or irreplaceable (or both)

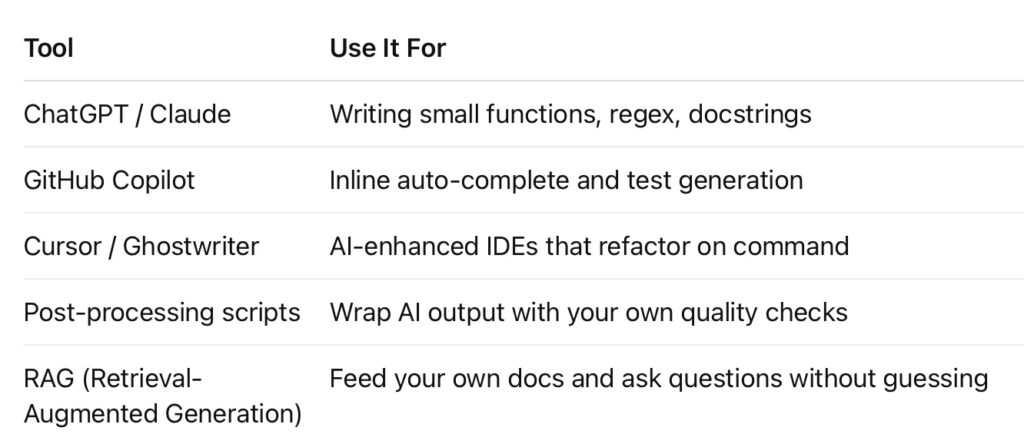

5. 🛠️ Tools, Tactics & Prompts to Keep in Your Pocket

🧷 Good Prompts for Code:

- “Write a Python function to X, and include input validation.”

- “Refactor this code to follow best practices in Django.”

- “Explain this code like I’m a junior dev.”

- “Generate tests for this function. Include edge cases.”

🧯 For Preventing Hallucinations:

- “If unsure, say ‘I don’t know.’ Do not guess.”

- “Only use real libraries, do not invent imports.”

- “Give links to docs if you cite tools.”

🧰 Tools to Get Comfortable With:

- GitHub Copilot

- GPT-4 for system design whiteboarding

- Claude for documentation and rubber ducking

- Local LLMs for sensitive/internal data

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) setups for team knowledge

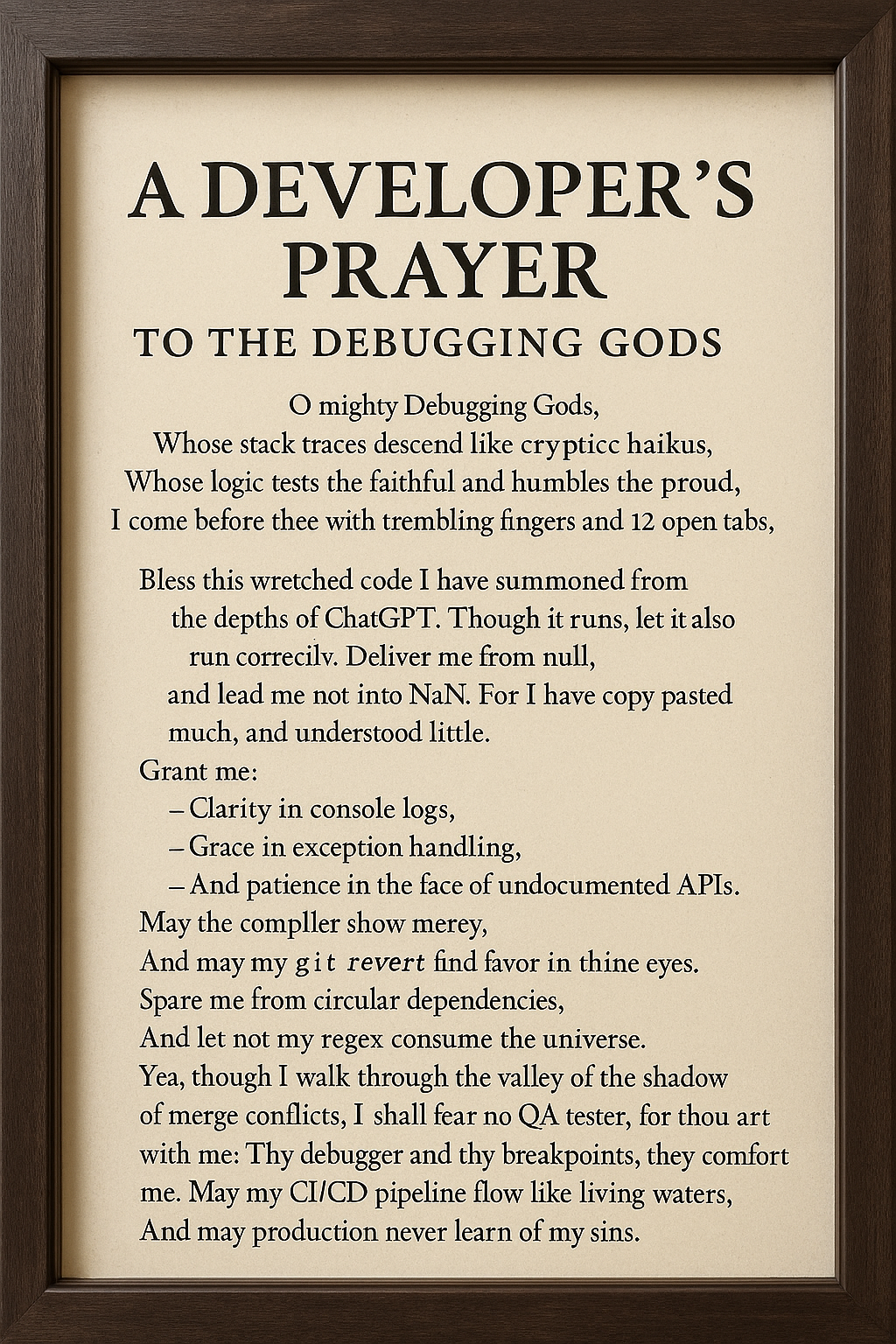

6. 🙏 The Developer’s Prayer to the Debugging Gods

Whisper this before every deployment.

Oh mighty Debugging Gods,

Whose stack traces descend like cryptic haikus,

Whose logic tests the faithful and humbles the proud,

I come before thee with trembling fingers and 12 open tabs.

Bless this code I summoned from ChatGPT. Though it runs, let it run correctly.

Deliver me from null, lead me not into NaN,

And forgive me for trusting that auto-generated test.

May the compiler show mercy,

May the git blame show not my name,

And may prod never know what I did in staging.

In the name of Turing, Python, and clean commits,

Amen.

7. 🧭 Final Notes from the Future

LLMs are not the end of programming.

They’re the beginning of a new skill stack.

You won’t survive by being a better typist.

You’ll survive — and thrive — by being:

- A better problem solver

- A faster integrator

- A cleverer AI prompt writer

- A deeply human mind working with a very powerful, very dumb machine

The good news?

If you’re reading this, you’re already ahead of the curve.

Now copy this handbook into your doc editor of choice, export it to PDF, print it out, and tape it to the inside of your laptop lid.

Then go forth and outsmart the bot.

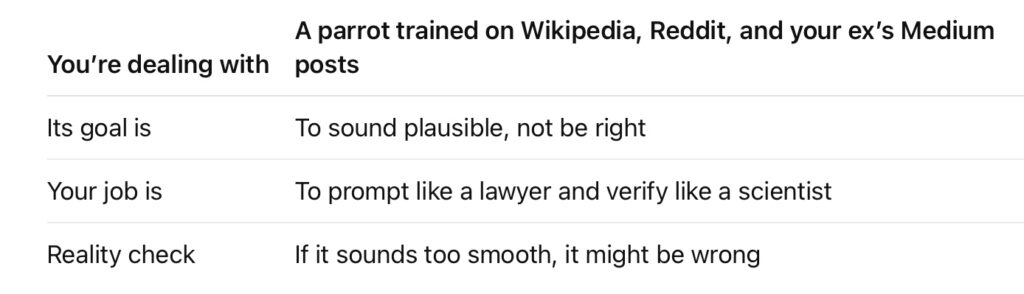

Your Job vs. The Confident Liar Bot

ChatGPT:

🧠💻

“Your Code, My Prompt: Surviving the AI Engineer Apocalypse”

Why Software Jobs Are Changing, and How to Keep Yours

🤖 1. Large Language Models (LLMs) Can Code — Kinda

Let’s start with the sparkly headline:

“AI is writing code now! Software engineers are doomed!”

Before you panic-apply to become a wilderness guide, let’s get specific:

- LLMs like ChatGPT, Claude, and Code Llama can absolutely write code.

- Need a Python function to reverse a string? ✅

- Want to build a chatbot that translates pig Latin into SQL? ✅

- Want it to debug your flaky production issue? ❌

- These models were trained on millions of lines of public code.

- GitHub, Stack Overflow, blog posts, etc.

- Which means they’re basically very fast, very confident interns who have read everything but understood nothing.

- They’re great at patterns, not meaning.

- LLMs predict the next token, not the best solution.

- They prioritize coherence over correctness.

- So they might write a method that looks perfect, but calls a nonexistent function named fix_everything_quickly().

🔥 2. Why This Still Freaks Everyone Out

Despite their tendency to hallucinate like a sleep-deprived developer on their fourth Red Bull, people are still panicking.

Here’s why:

- They’re fast.

One engineer with ChatGPT can write, test, and deploy code at 2x or 3x their old speed — for routine stuff. - They reduce headcount.

If 10 developers used to maintain a legacy app, now 3 + one chatbot can handle it.

(The chatbot doesn’t eat snacks or file HR complaints.) - They seem smart.

If you don’t look too closely, the code looks clean, well-commented, and confident.

Only after deploying it do you realize it’s also quietly setting your database on fire.

👩💻 3. So… Are Software Engineers Getting Replaced?

Short version: Some are.

Long version: Only the ones who act like robots.

- Companies are laying off engineers while saying things like:

“We’re streamlining our workforce and integrating AI tools.”

Translation: “We fired the junior devs and now use Copilot to build login forms.” - Engineers who:

- Only write boilerplate

- Never touch architecture

- Don’t adapt or upskill

…are more likely to get replaced by a chatbot that costs $20/month.

But the software job itself? Still very much alive. It’s just mutating.

🚧 4. Hallucination Is Still a Huge Problem

Remember: these models will confidently lie to you.

- They invent functions.

- Misuse libraries.

- Cite fake documentation.

- Tell you “it’s fine” when it absolutely isn’t.

Imagine asking a junior dev for help, and they respond:

“Sure, I already fixed it. I didn’t, but I’m very confident I did.”

That’s your LLM coding partner. Looks great in a code review, until production explodes at 3 a.m.

🧠 5. “Don’t Just Learn AI — Learn to Use It Better Than the People Trying to Replace You”

This is the actual career advice people need right now — not just “learn AI,” but:

Become the engineer who knows how to use AI smartly, safely, and strategically.

Here’s how:

- Use AI to enhance, not replace, your skills.

Automate the boring stuff: tests, docstrings, regex, error messages, documentation.

Focus your real time on architecture, systems, and big-brain work. - Catch AI’s mistakes.

Don’t just copy/paste. Always test, validate, and sanity check.

Be the one who catches the hallucinated method before it costs the company 4 hours and one lawsuit. - Build tools around the tools.

Use APIs like OpenAI or Claude to create internal dev tools, bots, onboarding assistants, etc.

Be the dev who integrates AI into the team’s workflow — not just another prompt monkey. - Teach others how to use it safely.

Become the “AI-savvy dev” everyone turns to.

Teach your team how to prompt, filter, and verify. That’s job security.

🔧 6. Tools & Tactics for Survival

🧙♂️ 7. The Future Engineer = Prompt Sorcerer + Code Wizard

Here’s the real shift happening:

Software engineers aren’t being replaced.

“Code typists” are.

The ones who thrive will:

- Use LLMs like power tools

- Know when the output is sketchy

- Integrate AI into dev pipelines

- Move from “just writing code” to designing the entire solution

📜 TL;DR (Too Logical; Didn’t Run)

- LLMs can code, but they still lie sometimes.

- Companies are using them to justify layoffs — but they still need humans who think.

- If you only “learn AI,” you’re one of a million.

- If you learn to wield it better than the people trying to automate you — you’re valuable.

Welcome to the age of human+AI engineering.

Keep your brain sharp, your prompts clean, and your rollback plan ready.

When Chemicals Do Zebra Art: The Magic of Turing Patterns

ChatGPT:

How Randomness Becomes Leopard Spots: Turing Patterns Explained

A Beautiful, Nerdy Tale of Physics, Chemistry, and a Little Mathematical Chaos

⸻

🔷 What Are Turing Patterns?

• In 1952, Alan Turing—yes, the codebreaker and father of computers—casually dropped a bombshell in biology: that natural patterns like zebra stripes or leopard spots can emerge from random chemical noise.

• Turing proposed that under the right conditions, a mix of chemicals could self-organize into complex, repeating patterns, without needing a genetic master plan or divine brushstrokes.

• These are now called Turing patterns. You’ve seen them:

• Stripes on zebras.

• Spots on leopards.

• Spiral patterns on seashells.

• That time you spilled two weird liquids on the carpet and they made a permanent art piece.

⸻

🧪 How It Works: Reaction + Diffusion = Drama

• A reaction-diffusion system is the stage on which Turing patterns dance.

• It combines:

• Chemical reactions (where substances transform each other),

• With diffusion (the tendency of things to spread out evenly, like bad decisions on social media).

• Normally, diffusion smooths things out. But sometimes, it does the opposite.

Under certain conditions, chemical reactions plus uneven spreading leads to instabilities—and out of that chaos, order emerges.

⸻

📐 Two-Ingredient Recipe for Pattern Magic

1. Activator: Promotes its own production and that of the inhibitor. Kind of a chemical hype-man.

2. Inhibitor: Slows things down. The chemical party pooper.

• These substances are both:

• Reacting with each other,

• And diffusing at different speeds.

• Here’s the twist: the inhibitor must diffuse faster than the activator.

• That imbalance can cause a small fluctuation to grow, creating a visible pattern.

Result? The chemicals go from “meh, I’m bored” to “let’s form a zebra.”

⸻

🔍 The Math, Gently

Let’s simplify what Turing actually did:

• He wrote down some differential equations. Something like:

\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} = f(u,v) + D_u \nabla^2 u

\frac{\partial v}{\partial t} = g(u,v) + D_v \nabla^2 v

• Don’t panic: these just describe how chemical concentrations change over time and space.

• u and v are chemical concentrations, D_u and D_v are diffusion rates.

• He looked at a steady state (where nothing changes) and asked, “What happens if we poke it a little?”

• Turns out, small pokes don’t fade—they grow. Certain wavelengths amplify and turn into patterns.

This is called a Turing instability—when a perfectly boring system goes rogue and starts making art.

⸻

🧪 Bonus Buzzword: What Is Diffusiophoresis?

Ah yes, the tongue-twister of the week.

📚 Etymology:

• “Diffusio-” → from Latin diffundere, “to spread out”

• “-phoresis” → from Greek phorein, “to carry or move”

So: diffusiophoresis = “to be carried by diffusion.”

🧼 Plain English Version:

• Imagine a chemical gradient—like soap molecules being thick in one spot and thin in another.

• Particles (like dirt, pigment cells, or your dignity) move through the fluid, not on their own, but because something else is diffusing around them.

• This is diffusiophoresis: movement caused by gradients in other substances.

• Think: soap dragging grime off your clothes because it’s moving through the water unevenly.

In reaction-diffusion systems, this adds real-world messiness—it explains why biological patterns aren’t perfectly sharp and symmetrical. They’re… natural.

⸻

🧬 Where Do We Use Turing’s Idea?

Here’s where Turing patterns go from abstract nerd-doodles to useful innovation:

• Tissue Engineering: Use Turing math to grow organs with natural blood vessel patterns.

• Camouflage Design: Bio-inspired clothing that adapts to environments (think octopus fashion).

• Soft Robotics: Materials that grow textures or patterns for grip, sensing, or intimidation.

• Synthetic Biology: Engineer bacteria that glow in stripes or dots.

• Ecosystem Modeling: Predict where vegetation clumps form in deserts (like fairy circles in Namibia).

• Neuroscience: Model how the brain folds during development (yes, your wrinkles may be math-related).

⸻

🌀 Chaos into Order: Why This Matters

• Turing’s theory is one of the first to mathematically prove that structure can emerge from randomness.

• No master architect needed—just local rules, some math, and a good chemical vibe.

• It shows that complexity isn’t designed—it emerges.

• And it applies not just in biology, but in chemistry, physics, art, and even galaxy formation.

⸻

🧠 TL;DR (Too Long; Dots Rule)

• Turing patterns = natural patterns created by chemical reactions and diffusion.

• Reaction-diffusion systems explain how these patterns emerge.

• Diffusiophoresis = particles getting shoved around by uneven concentrations of other stuff.

• Turing instabilities = when a smooth, uniform system starts generating structure all by itself.

• Applications range from zebra skin to robot skin to wearable camouflage, proving that nerds can design better fashion than most influencers.

⸻

So next time you see a cheetah, a coral reef, or an oddly patterned rug stain—remember:

It might just be the universe doing math.

And Turing? He was the first to catch it in the act.

Two Numbers, Infinite Complexity: The Real Math of Self-Driving AI

ChatGPT:

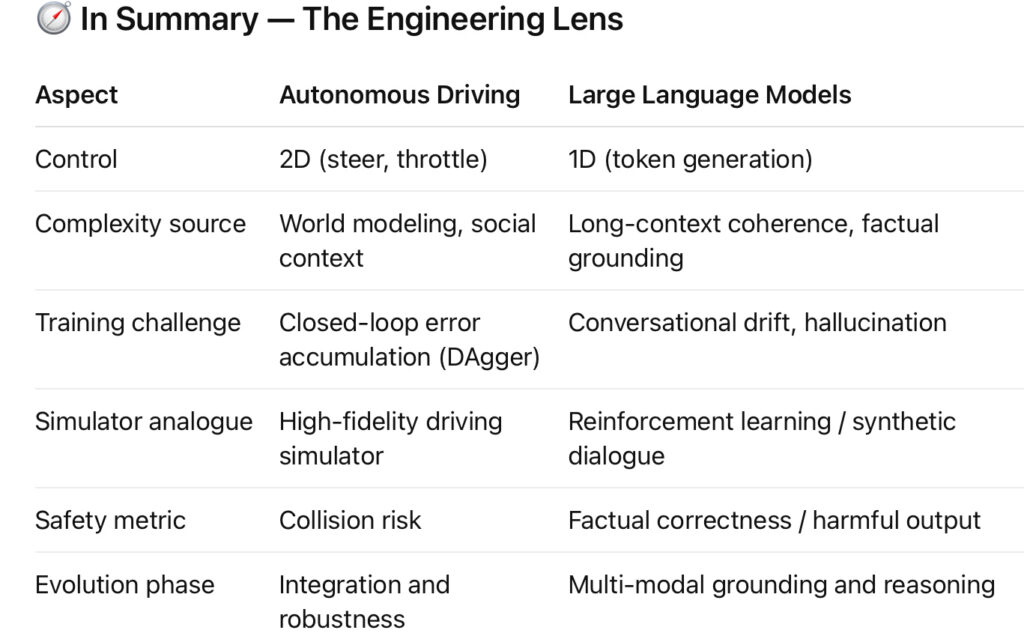

Here’s a detailed interpretation and commentary on the Waymo interview — from the perspective of AI engineering, connecting each idea to the underlying technical principles of autonomous systems and modern AI architectures:

🧩 1. The “Simplest” Problem That Isn’t Simple

At first glance, autonomous driving seems to require only two control outputs:

- Steering → left or right

- Throttle → accelerate or decelerate

That’s just two numbers.

But as the speaker notes, the simplicity is deceptive — because these two outputs depend on an astronomically complex perception and reasoning pipeline.

From an AI engineering standpoint:

- Those two numbers emerge from a stack of dozens of neural networks, each handling different tasks: object detection, semantic segmentation, trajectory prediction, risk estimation, and policy decision.

- The vehicle must construct a world model — a dynamic understanding of 3D space, actor intent, road geometry, and social norms — all from noisy multimodal inputs (camera, LiDAR, radar, GPS, IMU).

So while control space is 2-D, state space is effectively infinite-dimensional.

🧠 2. “Social Robots” and Multi-Agent Reasoning

Calling autonomous cars “social robots” is spot-on.

Unlike factory arms that operate in static, well-defined environments, cars interact continuously with other autonomous agents — humans, cyclists, other AVs.

Engineering implications:

- Driving models must handle intent prediction — e.g., will that pedestrian cross or just stand there?

- It’s a multi-agent game: each agent’s optimal action depends on others’ predicted actions.

- Solving this requires behavioral cloning, reinforcement learning (RL) in simulators, and game-theoretic policy training — similar to multi-agent RL in StarCraft or Go, but with 2-ton metal pieces and human lives involved.

🔁 3. Closed-Loop vs Open-Loop Learning (“The DAgger Problem”)

The “DAgger problem” (Dataset Aggregation) is a classic in robotics and imitation learning:

- In open-loop training, you feed prerecorded data to a model to predict the next action — fine for benchmarks.

- But in real-world driving, small prediction errors compound, drifting the system into unfamiliar states (covariate shift).

AI engineering solution:

- Use closed-loop simulators that allow the model to unroll its own actions, observe consequences, and learn from them.

- Combine imitation learning (to mimic human demos) with reinforcement fine-tuning (to recover from its own mistakes).

This mirrors the evolution of LLMs:

- If trained only on next-token prediction (open loop), they can veer off-topic in long dialogues — the linguistic version of drifting off the lane.

- Hence RLHF (reinforcement learning with human feedback) and online rollouts to correct trajectories — the same control philosophy.

🧮 4. Simulation Fidelity and Data Augmentation

Simulation is the backbone of safe autonomous system training.

Waymo’s approach highlights two critical kinds of fidelity:

- Geometric fidelity — realistic physics, road friction, sensor noise, collision dynamics.

→ Vital for control policies and motion planning. - Visual fidelity — the realism of lighting, textures, and atmospheric conditions.

→ Crucial for perception networks trained with synthetic imagery.

Modern AI makes both scalable through domain randomization and style transfer:

- A single spring driving clip can be turned into winter, night, or fog scenes using generative models.

- This massively multiplies data coverage — a kind of AI bootstrap where simulation feeds itself.

🌍 5. The Rise of Semantic Understanding (“World Knowledge”)

Earlier AV systems relied on hand-labeled datasets for every situation.

The current generation (using models like Gemini or GPT-Vision analogues) can generalize from world knowledge — zero-shot understanding that “an ambulance has flashing lights” or “an accident scene means stopped cars and debris.”

Technically, this reflects a shift toward:

- Multimodal foundation models that integrate vision, text, and contextual priors.

- Transfer learning across domains — from internet-scale semantics to driving-specific policies.

This reduces reliance on narrow, handcrafted datasets and allows rapid adaptation to new geographies or unseen scenarios.

🚗 6. Behavioral Calibration: “The Most Boring Driver Wins”

From a control-policy engineering view, the “boring driver” principle is optimal:

- Safety = minimizing variance in behavior relative to human expectations.

- AVs that are too timid create traffic friction; too aggressive cause accidents.

- Thus, engineers tune risk thresholds and planning cost functions to match the median human driver’s comfort envelope — balancing efficiency, legality, and predictability.

This is social calibration — a new dimension of alignment, not between AI and text (like in chatbots), but between AI and collective human driving culture.

🌐 7. Localization of Behavior and Cultural Context

Driving rules vary: Japan’s politeness and density differ from LA’s assertive flow.

From an AI-engineering perspective, this means:

- Models must adapt policy priors regionally, perhaps using fine-tuned reinforcement layers conditioned on local data.

- Sensor fusion remains universal, but behavioral inference modules may need localization.

This is a step toward geo-specific AI policy stacks, not unlike language models trained with regional linguistic norms.

🖐️ 8. The Challenge of Non-Verbal Cues

Recognizing hand signals, eye contact, and head motion introduces human-level perception problems:

- Requires pose estimation, temporal tracking, and intent inference.

- These are frontier challenges in multimodal understanding — fusing kinematics and semantics.

AI engineers tackle this with:

- Video transformers for gesture prediction.

- Sensor fusion that integrates camera, radar Doppler (for micro-movements), and contextual priors (“a traffic officer is present”).

- Heuristic and data-driven hybrid systems to ensure interpretability.

🧱 9. Safety Engineering and Counterfactual Simulation

Waymo’s replay of every incident in simulation shows a system-engineering discipline borrowed from aerospace:

- Run counterfactuals (e.g., what if the human driver was drunk?)

- Update policies defensively, even when not legally at fault.

This builds redundant safety layers:

- Continuous policy retraining with near-miss data.

- Scenario libraries to test for tail risks (multi-car pileups, sudden occlusions, sensor failures).

It’s the real-world version of unit testing for neural policies.

🔮 10. 30 Years, Five Generations, and No “Breakthrough” Left

Vanhoucke’s remark — “no new breakthroughs needed” — is an engineer’s way of saying we’re now in the scaling regime:

The analogy to LLMs is clear: we’re post-revolution, entering the engineering maturity phase, where the next 5% of improvement requires 500% more testing.

All core components (perception, prediction, planning) exist.

The frontier is integration, safety certification, and reliability under edge cases.

Bottom line:

Autonomous driving isn’t “solved” because it’s not merely a control problem — it’s a context-understanding problem in motion.

It fuses perception, reasoning, ethics, and social psychology into an engineering system that must behave safely in an unpredictable human world — the same challenge facing all embodied AI systems today.

Living on the Exponential Curve: Why A.I. Keeps Outrunning Us

ChatGPT:

From Linear Brains to Exponential Machines: Why Humans Keep Being Shocked by A.I. (and How to Stop Panicking)

🧠 1. Our Brains Are Linear, Like 1980s Spreadsheets

- Humans are great at counting sheep, stacking bricks, and predicting tomorrow’s grocery prices.

- Our intuition evolved in a world where everything happened gradually: one sunrise per day, one baby per mother, one harvest per year.

- We expect steady progress — “a little better each year.” That’s linear thinking.

- In math terms, we imagine growth like this:

→ 1 → 2 → 3 → 4 → 5 - It’s comforting, predictable, and easy to fit on a tax form.

🚀 2. But Exponential Growth Laughs at Your Gut Feeling

- Exponential growth doesn’t add — it multiplies.

→ 1 → 2 → 4 → 8 → 16 → 32 → BOOM. - The human brain handles this about as well as a hamster handles quantum physics.

- Early on, exponential change looks boringly flat — nothing dramatic happens. Then suddenly it takes off so fast people yell “It came out of nowhere!”

- That’s the illusion of gradualness: you don’t notice the explosion until it’s already in your living room.

⚙️ 3. Welcome to the Exponential Curve of A.I.

- The history of artificial intelligence is a perfect example of exponential growth disguised as “slow progress.”

- For decades, A.I. was a research curiosity — clunky chess programs and awkward chatbots.

- Then around 2012, deep learning and GPUs joined forces, and the curve started to tilt.

- Today, we’ve gone from recognizing cats in photos to writing college essays, composing symphonies, diagnosing tumors, and generating movie scripts — all in barely a decade.

- Each A.I. generation builds on the previous one: more data → better models → more users → even more data → better models again.

It’s the technological version of sourdough yeast: it feeds on its own growth.

📈 4. Why Linear Minds Keep Missing the Takeoff

- When A.I. improved 10% a year, it looked manageable. But exponential doubling means:

- The same “10% progress” last year equals “world-changing leap” this year.

- By the time humans notice the curve, it’s already vertical.

- Our brains evolved to track rhinos, not logarithms.